Bradford riots 2001: What has changed 20 years on?

- Published

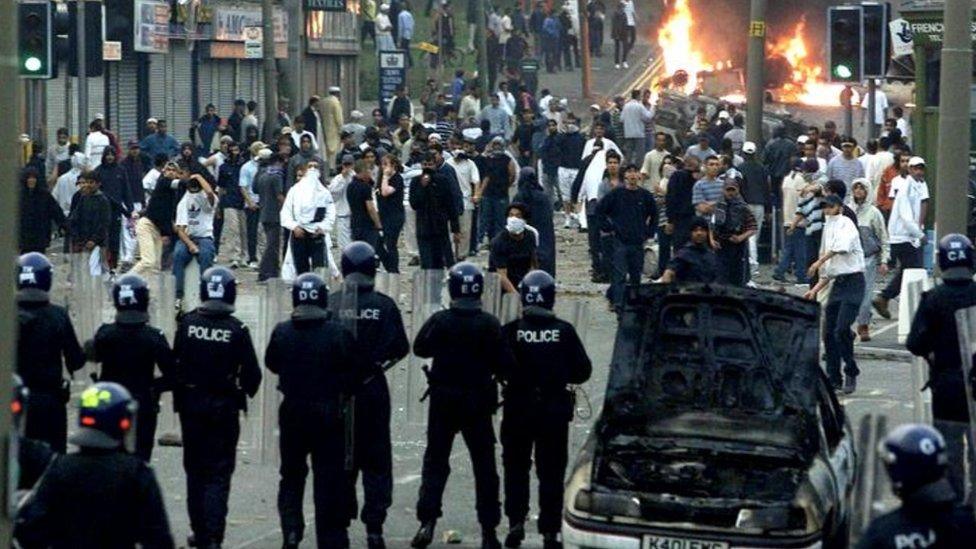

The riots followed an attempt by the National Front to march through Bradford

In July 2001, intense rioting in Bradford represented some of Britain's worst mainland violence in decades. Business and shops were destroyed, hundreds of police were injured and almost as many protesters arrested. Twenty years on, the BBC has spoken to some of those who were there about the scars left by the disorder and how the city has looked to heal.

Memories of the night are clear - burning cars, the smell of petrol bombs, the barricade between rioters and police, both sides refusing to give up ground.

It was mid-afternoon on 7 July 2001 when the sparks of trouble began to flare. By nightfall whole pockets of the city were aflame. During nine hours of violence, thick black smoke and fumes drifted down a half-mile length of road as police tried to beat rioters back. A social club was firebombed, trapping 23 people inside before they were rescued. A BMW dealership was looted and burnt down.

When it was all over, the cost of the damage had mounted to an estimated £27m.

Ali (not his real name), was a 17-year-old Bradford College student at the time. He had wandered into town with friends. They had heard mounting rumours of a National Front march through Bradford, planned in defiance of a government ban. Trouble had broken out previously, in Oldham and Burnley, when far-right extremists targeted towns in the depressed industrial north with a high percentage of Asian residents.

In Bradford city centre, anger mounted as word spread that police had allowed National Front sympathisers to gather in a pub. As they emerged from the building, the right-wing shouted abuse at Asian youths, viciously attacking one.

Disorder was to follow. Hundreds of young men descended on the city, angry at the events of the day. Tensions escalated as protesters were pushed up White Abbey Road by police and violence between the two sides spiralled out of control.

"There were so many people - police officers, young Asian lads, white lads, mixed Caribbean," says Ali. "Slowly I got drawn into the excitement of what was happening. I went straight to the front, then the next thing, I was there throwing stones at police."

Rioters hurled petrol bombs, bricks and bottles at police

Almost 1,000 officers were eventually brought in to tackle the riots, with some 300 injured. Brian Booth was one. The young PC had been with West Yorkshire Police for just a month when he found himself on the front line, fearing for his life.

"We had bricks, sticks, fireworks, petrol bombs thrown at us," he recalls. "I vividly remember coming up Whetley Hill when a car pulled up and was set on fire, loaded with Calor gas bottles. It was rolling towards our front line at such a speed that I thought: 'By the time that hits us, it'll explode'.

Mr Booth, now chairman of West Yorkshire Police Federation, witnessed officers falling to the left and right of him, some severely injured. He was left with severe burns on his legs from where his protective pads had rubbed off the skin. He still suffers from the effects of torn ligaments.

"I don't know how many bricks I took that night on my helmet. I had massive whiplash injuries at the end," he says.

Brian Booth had nightmares and suffered post-traumatic stress disorder after policing the riots

Some 200 people were locked up for their part in the violence. More are thought to have joined in. Ali, who was given a four-and-a-half year sentence for his role, believes young members of a struggling Asian community, dealing with poverty and a loss of jobs from deindustrialisation, felt further denigrated by the provocation of the far-right. He remembers a desire to protect his city from the threat of the National Front.

"I felt like a soldier and that I could do something," he says. "Every rioter had their own story for being there. You could see when they were throwing things, their anger and frustrations."

Disillusioned by his family's experience of racism, Ali shunned the acquiescent attitude of his parents, who had come from Pakistan so his father could work in the textile industry.

"They'd walk down the streets and maybe the white community didn't know how to handle it, but they were called names, windows were put through if they lived in a certain area," he says. "They would work harder than others, knowing that the white supervisor would let them work harder. I understood racism more and I could challenge it, but maybe the elders at the time didn't."

Manningham Ward Labour Club was firebombed, trapping 23 people inside who were all eventually led to safety

Far from relieving tensions, the sentences given to those involved meant a community that already felt under attack saw it as a racist approach to justice. Families of those jailed - many for up to five years - felt they were treated harshly in comparison to white men sentenced over other public disorders.

But, nine years later, the men's experiences proved instrumental in preventing a repeat of the riots when the English Defence League staged a protest in Bradford in 2010.

"Those young men began to organise to make sure their nephews, brothers and sons did not get provoked in the way they had been provoked," says academic Jenny Pearce, who worked with organisations in the aftermath of the 2001 disorder.

Ms Pearce, who co-authored a book on the riots while at the University of Bradford's Department of Peace Studies, said the community and police had learned lessons from 2001. Officers realised they had been heavy-handed and began to rebuild connections with the community.

Twenty years later, opinion is divided on whether enough has been done to change Bradford. In the immediate aftermath of the riots, reports by Lord Ouseley and Ted Cantle painted a picture of a fractured city with mistrust between different communities.

The riots resulted in 297 arrests, 187 people being charged and 200 jail sentences totalling 604 years

But Bradford Labour councillor Mohammed Amran believes integration has "massively improved" and the city is one to be proud of.

"Back then, Bradford was segregated. There were defined Asian and white areas and you didn't mingle because of the fear of how you'd be treated," he says. "There just wasn't the push for integration and cohesion that we see today."

Once a critic of the police, Mr Amran says Asian communities in 2001 had little confidence in officers and "felt on their own" but now they worked together. He describes a city where "Asians, blacks and whites" play in the same parks, "people speak to each other" and "white people drink tea in cafes on Oak Lane" - something which once would have been unthinkable.

But Zahida Khan, who campaigned over the sentences handed out after her brother was jailed for rioting, believes the city still bears the scars.

"Are we nurturing young people enough? No. Have we developed economically? No. Have we attracted new business here? No."

"We have to acknowledge that the far-right does exist and that it does threaten minority communities. We have councillors and MPs but are they really in touch with us?"

Mohammed Amran, pictured in 2001, believes there have been big improvements in cohesion and integration since the riots

Youth worker Sharat Hussain was in the thick of the unrest in 2001 trying to calm angry rioters. He says Bradford has grown into a thriving multi-cultural city but he fears the effects of under-investment in youth services.

"Slashing funding has led to high levels of crime and anti-social behaviour among young people. They don't have coping strategies so end up in criminality," he says.

After losing his job as a Bradford Council youth worker due to budget cuts, he transformed St Mary Magdalene Church in Manningham - which was at the heart of the riots - into a community and youth hub.

"We need to start looking at the bigger picture - we need better education, health, housing. We need more investment in bringing business to the city," he says. "It's just full of charity shops and so there's little job opportunities. Young Asian men may end up following their forefathers and working in car washes, taxis, low-paid jobs, so there's more temptation to get involved in crime."

Sharat Hussain, in the red football shirt, has turned a dilapidated church into a community hub for youngsters

Bradford district commander, Ch Supt Daniel Greenwood, says police have worked hard alongside other agencies and communities on how they listen and respond to concerns.

Neighbourhood policing, he says, is "vastly different" compared with 2001 and officers were "much better-trained in diversity, community inclusion and faith awareness".

He said there was increased accountability and scrutiny to improve public confidence and police had worked with schools, businesses, the council and communities to address the issues that led to the riots.

He says Bradford "is a city which is celebrating its diversity, which is looking forward and a city which is proud of its progress".

For Ali, the time he spent in prison for his actions on that summer's day changed his life. He was sentenced to four and a half years but his term was reduced to 12 months because of his good character.

Now a married father of three, his experience in jail inspired him to continue his education and work with young people to change their behaviour.

"It's like if you hit someone, you think they deserved it at the time but you end up regretting it. That's what happened with me in the riots," he says.

"I want to support young people now so they don't make the mistakes that I did."

Related topics

- Published7 July 2011

- Published6 July 2011