Richard III dig: Grim clues to the death of a king

- Published

The decisive act: Richard III leads a charge of his knights in an attempt to kill rival Henry Tudor and, despite getting close enough to strike down Henry's standard bearer, became surrounded moments later

If you know a quotation from Shakespeare's Richard III, chances are it is the king's last, desperate plea to escape his fate.

But the writer's imagination aside, the discovery of his skeleton beneath a Leicester car park - combined with historical research and weapons analysis - means we now are closer to the grisly truth.

And that truth combines heroic chivalry with the most visceral realities of medieval hand-to-hand combat.

Despite being one of the most pivotal events in English history, reliable accounts of the Battle of Bosworth in general, and Richard's death in particular, are patchy.

However, what information the chronicles do provide tells an extraordinary story.

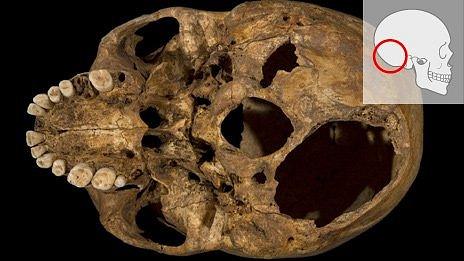

The major wounds are to the base of the skull, either side of the spine, and would have been caused by heavy bladed weapons

On 22 August 1485, Richard met his rival Henry Tudor - the soon-to-be Henry VII - in fields near Market Bosworth in Leicestershire.

Most sources agree Richard's army was larger, but it failed to sweep his enemy from the field.

Dr Steven Gunn, a fellow in modern history at Merton College, Oxford, said Tudor historian Polydore Vergil wrote a vivid account of Richard's next, extraordinary, move.

He explained: "He says spies told Richard that Henry was riding with a small number of men, so when he sees this, Richard leads a charge straight at him.

"He then goes on to say: 'In the first charge Richard killed several men; toppled Henry's standard, along with the standard-bearer William Brandon; contended with John Cheney, a man of surpassing bravery, who stood in his way, and thrust him to the ground with great force; and made a path for himself through the press of steel.'

"Richard is then surrounded by enemy troops but Vergil only says he was killed 'fighting in the thickest of the press'.

"More detail comes from a Burgundian historian Jean Molinet, who describes Richard's horse becoming stuck in a marsh and then 'unhorsed and overpowered, the king was hacked to death by Welsh soldiers'."

When the discovery of the bones was announced, it was confirmed they showed signs of major head trauma. After more than four months of study, the research team has drawn its first conclusions.

Of 10 injuries visible on the skeleton there are eight on the skull alone.

University of Leicester osteo-archaeologist, Dr Jo Appleby said the most obvious damage was at the back of the skull.

"The appearance of this injury is typical of an attack with a large-bladed weapon which was sufficiently sharp to slice off a large area of bone from near the base of the skull.

"Although we cannot identify the specific weapon that caused this injury, it would be consistent with a halberd or similar weapon.

A boar badge - the symbol of Richard's household - was found at Bosworth and may mark his final stand

"This wound is likely to have been fatal, although that would have depended on exactly how far the blade penetrated into the brain."

A second wound on the other side of the spine indicates where a blade was forced deep into the skull.

Another wound had taken a small chunk out of the top of the head.

"This wound was caused by something hitting the top of the skull sufficiently hard to push in two flaps of bone on the inside surface. Although it looks dramatic, this wound would probably not have been fatal," said Dr Appleby.

She added: "We have evidence of significant injuries on the skeleton, but we cannot conclusively prove that they were the cause of death.

"There are many ways of killing someone that leave no traces on the bones, even in a battle situation."

Robert Woosnam-Savage is curator of European edged weapons at the Royal Armouries Museum in Leeds and has also studied Richard's skeleton.

He said: "Medieval battlefields saw an array of weapons used, from swords, battle hammers, maces, arrows and even early firearms.

"Most of the 'common' foot soldiers would have used staff weapons, such as bills or halberds, which have heavy cutting blades, often with a spike, mounted on a long wooden haft.

"Many of these were designed to be able to punch through elements of armour, or at least damage it in such a way that it no longer functioned."

Mr Woosnam-Savage said using the physical evidence and historical accounts, a possible scenario could be imagined.

Halberds were among the most common weapons used by foot soldiers at Bosworth

"Richard probably got within a few yards of Henry before his horse probably became stuck in marshy ground or was killed from underneath him. On foot, with foot soldiers closing in, the fight becomes a close infantry melee.

"It would have been difficult to get through the armour, so attackers would have gone for gaps, or tried to break pieces off.

"The skeleton only shows the minimum number of injuries - the soft tissue has gone - and he is likely to have taken many more wounds of which there is now no trace.

"At some point he loses his helmet and then the violent blows start raining down on the head, including a possible blow from a weapon like a halberd, including the one which I think kills him.

"Then I think it possible that someone has come along, almost immediately afterwards, possibly with his body lying face down and stuck a dagger into his head.

"From becoming unhorsed, it probably only took a matter of a few minutes, before he was dead - not a long time at all."