Kegworth air disaster: Plane crash survivors' stories

- Published

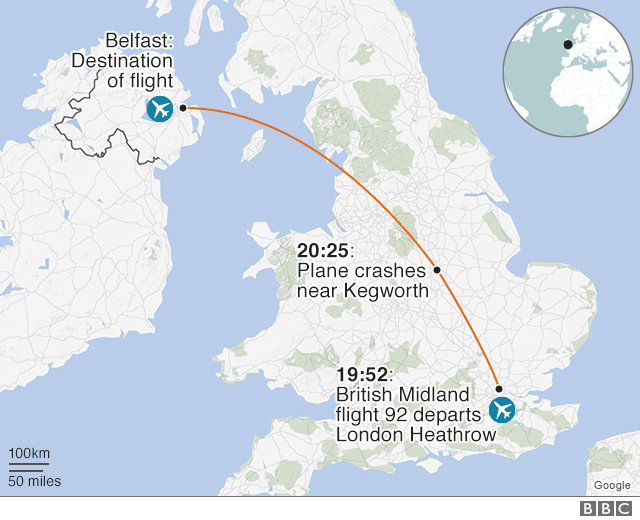

The Kegworth air disaster in 1989 killed 47 people and left wreckage strewn across the M1. Despite the catastrophic damage it caused, a remarkable number of passengers survived the tragedy 25 years ago. This is their story.

Chris Thompson is a survivor, pulled unconscious from the mangled remains of British Midland flight 92.

Along with 117 other passengers, he'd sat helpless as the stricken Boeing 737 - having lost both engines - lurched sickeningly and plunged towards a busy motorway.

Months after the crash, when he'd learned to walk again, he somehow managed to summon the courage to get back on a plane.

But he couldn't fly without alcohol or tranquillisers. And at the check-in desk he was haunted by his knowledge of Flight 92's seating layout.

Chris refused to travel in certain parts of the cabin. He couldn't sit in what he called the "dead seats".

Today, sitting in his seafront home in Northern Ireland, he says he's managed to conquer most of those fears.

But a quarter of a century after the night which changed his life, the memories are still vivid and his hands shake violently as he recalls the moment he realised he was probably going to die.

News of the plane crash was broken on BBC Two by Michael Buerk

"The lights were flickering as the engine spluttered and died and came on again," he says.

"Part of your brain's saying 'it can't be happening' and the other part of your brain is sitting through it and you've nowhere to run.

"There's nothing you can do. You are completely, completely helpless."

Then a 33-year-old father-of-one, Chris had been looking forward to getting home to Belfast after a day at the London Boat Show, where he'd been scouting for equipment to sell in his chain of sports shops.

He was a seasoned flyer - travelling up to 35 times a year - and about 15 minutes after boarding the 19:50 British Midland flight from Heathrow, he was relaxing in row one with a meal and a glass of wine.

The next moment, his nerves were shattered by an explosion.

"We've heard bombs in Belfast for years," says Chris. "It wasn't a bomb."

"It was just a huge, like an enormous backfire bang and the plane lurched."

Sitting further back was 62-year-old Alan Johnston, one of the oldest travellers on the flight, who'd been in London visiting his first grandchild - a girl, born the day before the Lockerbie bombing.

For years, Alan had worked in the oil industry, often flying on ancient, unreliable planes. He'd had a couple of close shaves in the Middle East and Africa.

To him, this was a safe, short flight on a modern aircraft in a part of the world with an excellent safety record.

So while the loud bang terrified other passengers, Alan hardly batted an eyelid. His daughter had bought him a particularly gripping book and he intended to enjoy it.

Even when the plane began to shake, Alan read on.

Many around him, however, were beginning to panic - especially those who had noticed smoke drifting into the cabin.

Speaking over the tannoy, Captain Kevin Hunt tried to reassure them.

The right-side engine was malfunctioning, he announced calmly. He was preparing to shut it down and divert the plane to East Midlands Airport - base of the British Midland fleet.

It seemed that Alan's resolve had been justified - the problem was in hand, and would be nothing more than an inconvenience.

As Captain Hunt reduced power the plane stabilised and peace gradually returned to the cabin. The smoke seemed to dissipate. Crew began to tidy away the half-eaten meals in preparation for landing at East Midlands - which was now only a few minutes away.

But at the back of the plane there was unease among a small group of passengers.

It wasn't that they objected to the captain's decision to turn off the engine. It was his choice of engine that was causing concern.

Looking out of the cabin windows, they'd seen sparks and flames, and were in little doubt the damage was serious. But this was on the left side of the plane, not the right.

Among the bewildered group was Mervyn Finlay, who was sitting by a window in row 21.

The bread delivery man from Dungannon had also been at the London Boat Show, and had managed to catch an earlier-than-planned flight back from Heathrow. He shouldn't have been on that plane.

Now, instead of unwinding while he flew home to his wife and young son, he was grappling with the knowledge that the pilot might have made a serious error.

Had Captain Hunt switched off the wrong engine, leaving them at the mercy of a broken one?

"We were thinking: 'Why is he doing that?' because we saw flames coming out of the left engine. But I was only a bread man. What did I know?"

And then there was another loud bang.

Today, sitting in his comfortable living room, Chris Thompson closes his eyes as he recounts what happened next, one hand clutching the other to calm the shaking.

"You are immediately aware that you are thousands of feet in the air," he says.

"At this time it's dark outside. I can see the lines of lights down below from roads and this thing suddenly lurches and there's a big bang. And then there's another big bang.

"At that point it started lurching around all over the sky. That was horrendous and my skin just absolutely crawled because… we weren't on the ground, we weren't anywhere near the ground.

"I absolutely guarantee," he adds with conviction. "If there had been a way off that plane, people would have killed each other to get off."

As the plane lurched, passengers became gripped with panic, screaming, pleading with the engine to work and clutching one another for comfort.

Planes still fly low over the M1 to land at East Midlands Airport

By now, even Alan Johnston had to admit he was worried about the condition of the aircraft.

"Vibration is an understatement," he says. "It was like a load of large-sized gravel being suddenly shovelled into a washing machine. It was that noise, plus violent vibration.

"[It was] something I had never experienced before and I tried to divert my mind as best I could."

But there were still a few pockets of calm.

Dominica McGowan tried to convince the woman next to her they were "just going to come down with a bump".

The then 37-year-old mother-of-three had been studying psychotherapy in London, and she drew on her training to reassure those around her.

Even today she remains cool, almost detached, as she recalls that night - though she admits she's "blocked out" some of the horrors.

"It makes sense [not to think about what is happening]. Who would ever think they'd be in a plane crash? So I suppose there was an element of that."

She calmly explained to her companion how they would simply "belly-flop" on to the runway.

But it wasn't to be.

As panic escalated among other passengers, all that could be heard in the cabin was the whistle of the wind, mixed with screams and whimpers.

The wrecked engine gave a few dying sputters and jolts.

And then it gave out completely.

As the plane plummeted, survivors remember feeling their stomachs "leap" as if they were on a rollercoaster going over the top.

Chris Thompson looked out of the window and saw they were still nowhere near the ground. Far below him the lights of a motorway weaved dizzyingly.

It was then he realised - at this height and with no engines - there was little chance they would survive.

He began struggling to breathe as panic, compounded by g-force, gripped his body.

For all the passengers, those terrifying few seconds hurtling to the ground stretched out into minutes.

Then the captain called "brace, brace" for crash landing.

Moments before impact, Alan and Chris watched in confusion as a church spire sailed past the windows. It was then they realised how quickly they'd descended.

"Your brain says: 'What? It can't be. It can't be.' Then you think: 'I'm about to die. No, I can't be because I'm an optimist. It can't be,'" says Chris.

"The next thing was an enormous crushing."

Forty-five minutes after taking off from Heathrow, British Midland Flight 92 crashed into the M1.

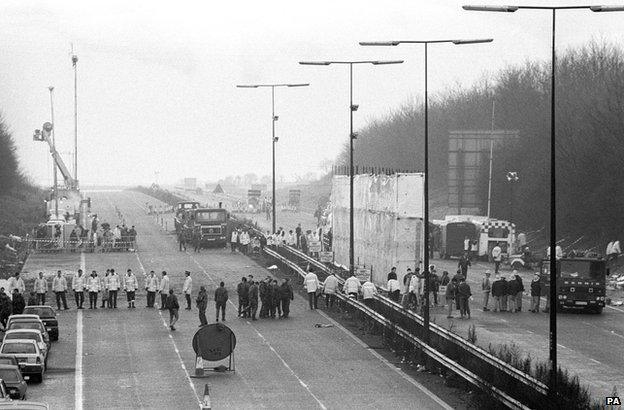

Travelling at about 130mph, it hit a field on the southbound side of the motorway before plunging through trees and smashing into the embankment on the opposite carriageway.

On impact, the front section of the plane - carrying about 15 people - broke away from the main body.

The tail snapped off, flipped over, and landed upside-down on top of the right wing, alongside the mid-section of the fuselage.

Inside, all but one overhead locker sprang open and luggage flew through the air, causing head injuries to almost every passenger, and killing some of them.

Chairs shot forward, crushing people between the seats and causing horrendous leg wounds.

The plane had come down yards from the village of Kegworth, just a few hundred feet short of the runway at East Midlands Airport.

Moments earlier, two motorists had seen sparks flying from the jet as it descended towards them. Realising it was about to crash, they managed to slow traffic using their hazard-warning lights. It is still regarded as a miracle that no-one on the motorway was hurt.

The people of Kegworth are accustomed to the rumble of landing aircraft. But the thunderous rattle that shook their homes that quiet Sunday evening, as many of them settled down to watch television, was something else entirely.

A few people outside at the time, driving home or walking their dogs, had caught sight of the plane as it plunged towards the village.

Their eyes were first drawn to orange streaks in the winter sky. Then they saw the stricken jet - one engine spurting flames as chunks of burning metal fell away.

At the airport, emergency crews were patiently waiting for Flight 92 to land. They were often called when an aircraft had mechanical problems. Even with one engine, they always landed safely.

Among them was Dave Astle. The part-time firefighter from Melbourne in Derbyshire had been at his four-year-old daughter's birthday party when the call came in.

For Dave, this was routine - nothing more than a precaution.

"It was coming in quite normal," he says. "We were watching it coming in and then it just disappeared in a cloud of smoke."

With horror, they realised the plane had actually crashed.

Using an airport access road, the fire engine got them as close to the scene as possible, before they scrabbled through trees and bushes to reach the edge of the motorway.

They found the remains of a Boeing 737, smoking and shattered into three pieces on the embankment.

As he recalls that night, Dave talks softly and drums his fingers on the table, often needing a prompt to describe what he saw.

Already, four people were out of the wreckage - he believes thrown from the plane - with one stuck in a tree, still in her seat.

"It was quiet. Very, very quiet. Horrible really. They [the four survivors] didn't say anything. Whether they realised what had happened I don't know," Dave says.

Stepping into the eerie darkness of the upturned tail section, he could see passengers hanging upside down from their seats, many with twisted limbs, shattered ankles and lacerated faces.

Others were buried completely under the luggage strewn across the cabin.

But it was the smell that really stuck in his memory.

"I cannot describe it and I can't relate it to anything," he says.

"There was food on board and drink - you've got that smell as well. Spirits you could smell. This smell was something I've never experienced before or since. They said it was the smell of death."

Another man who braved the carnage of the crash site was Graham Pearson - the only civilian rescuer to set foot inside the plane.

The Royal Marine and his wife Rosie were driving north up the M1 when the 737 roared overhead.

Only five minutes earlier, the pair had stopped for a break at a service station. Had they not, it would probably have been an uneventful journey home.

Graham clambered up the embankment to get to the wreckage, ignoring the risk of fire from the still-burning engine.

Inside he found Alice O'Hagan, who'd been travelling with her husband Eamon.

Like many of the passengers, they were trapped between broken seats that had been thrown forward on impact.

Alice tried to free herself, but couldn't. Looking down, she realised why.

Speaking to BBC documentary Collision Course in 2003, she said: "I don't know where I got the strength from but as I pushed the seat forward my feet came away. And as my feet came away I could see they were hanging off."

Graham came to Alice's aid, and began working to stem the blood pumping from her shattered legs.

Then he heard another woman cry out.

With tears in his eyes as he recalled the rescue, he told the programme: "At that moment in time it was quite quiet. People had just started to come out of unconsciousness or slowly started to realise what was going on.

"I heard this woman's voice and she was calling for help to get a baby out.

"Being a father with children myself I could relate to that... it was like a magnet really, that's what drew me to that part of the plane."

After much effort, he managed to free seven-month-old Ryan McCallion who was shielded by his mother but trapped under several bodies.

The boy made a full recovery, but his mother Ruth was not so lucky. She died in hospital three weeks later, shortly before she was due to return home.

Graham was hailed a hero for the three-and-a-half hours he spent helping passengers. But the experience haunted him for years.

Flashbacks and recurring nightmares cost him his job and almost destroyed his marriage. In 1998 he successfully sued British Midland for £57,000, external.

Few, if any, escaped without some kind of physical or mental trauma. But Dominica McGowan was one of the most resilient.

Moments after regaining consciousness she managed to free herself from her seat and - like many others - was immediately struck by the absolute silence.

"I heard no sound," she says. "Not a sound."

"And I remember darkness. And I remember thinking: 'I need to get out of here'."

Although she didn't know it, she had shattered her pelvis, broken all of her ribs, punctured a lung and broken her back.

Despite her severe injuries, she somehow managed to haul herself over unconscious passengers, and crawl through the cabin debris to an emergency exit.

Outside, the engine fire was still burning and aviation fuel was running down the bank like a river.

To prevent an explosion, firefighters were dousing everything with foam.

By now, police officers had also started arriving. Like the firefighters, many thought they were on a training exercise until confronted with the twisted remains of the plane.

"When we saw the aircraft, you could have heard a pin drop because then everyone realised, no-one staged this," says Ch Supt Jack Atwal - then a 24-year-old constable two days out of probation.

He was the youngest officer on site and remembers having a clear view inside the plane as he helped survivors.

"It was an unpleasant scene. A lot of injuries to the lower limbs, blood, visible leg injuries," he says.

He also recalls speaking to some of the survivors, including one badly hurt man who wondered if the young officer might go and look for his duty-free.

"I'm not sure if it was adrenaline or whether he was joking. I don't know if he realised the extent of his injuries," he adds.

Passengers, both alive and dead, continued to be pulled from the wreckage. Volunteers carried them to ambulances or to a temporary morgue established on the bank side.

Firefighters, doctors and nurses made their way through the plane, quickly assessing who could easily be removed and taken to hospital.

Among the dead, dying and seriously injured lay Alan Johnston, slipping into unconsciousness.

If not for a group of RNLI volunteers who had joined the rescue, he believes he would probably have been assumed deceased.

"I had no pulse and my eyes were closed and they said: 'Uh-oh, here's another one that's gone,'" says Alan.

"And then I twitched an eye. And their lifeboat training was such that it indicated there was still life."

He had severe internal bleeding and would later need "buckets of blood" to keep him alive.

Twenty-five-years later, Alan is talkative, cheerful and animated, and far less guarded than other survivors.

But sadness creeps into his voice when he remembers the aftermath of the crash, as rescuers tried desperately to reach those trapped deep inside the wreckage.

They were trying to get to passengers like Chris Thompson, buried at the front of the plane under a pile of luggage flung out of the overhead lockers.

He has no recollection of the rescue but was told it took more than two hours to cut him free.

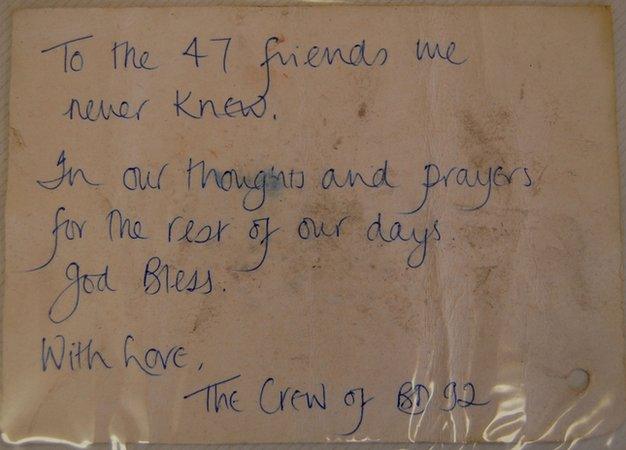

Scores of tributes to those killed were left at the scene by relatives, villagers and the emergency services

Rescuers worked through the night to recover the injured and the dead.

Dozens of motorists pulled over to help emergency crews, along with residents from nearby Kegworth.

One man - an AA mechanic - cut makeshift steps into the embankment so a human chain could be formed between the crash site and waiting ambulances.

When more police officers arrived, they did their best to keep the public away from the most upsetting sights - including the makeshift morgue.

In all, there were 79 survivors. Of those, 74 had serious injuries including broken backs, fractured skulls and brain damage.

Among them was Captain Kevin Hunt, trapped but conscious in his seat for more than two hours.

Thirty-nine passengers died on the night, and a further eight succumbed to their injuries in the following days.

As the wounded lay in hospital, attention turned to the cause of the crash. The Boeing 737 was a state-of-the art passenger jet with an impeccable safety record - what could have gone wrong?

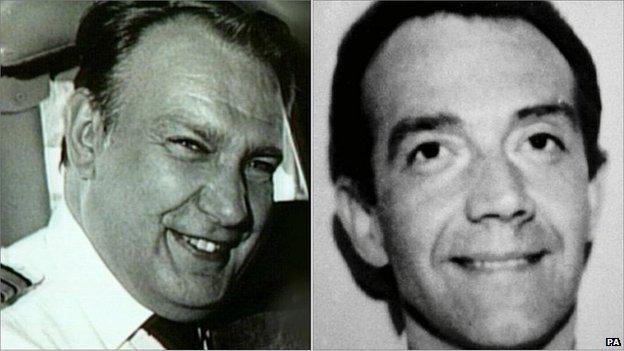

"It's the le… It's the right one." The words of first officer David McClelland - captured by Flight 92's data recorder shortly after the first jolt shook the plane.

For air crash investigators, McClelland's hesitancy was deeply troubling.

It suggested the unthinkable - that two experienced pilots, responsible for the lives of 118 passengers, couldn't be certain which of their engines was noisily deteriorating.

But how was that possible? The 737-400's cockpit had an array of instruments for monitoring each engine. It should have been obvious.

The Air Accident Investigation Branch (AAIB) team called to get to the bottom of the tragedy had seen more than its fair share of trauma in recent weeks.

Since late December they had been sifting through the grim remains of the deadliest terror attack in British history, at Lockerbie.

So far, it had been a gruelling exercise, and some of the team were taking an overdue Christmas break - including senior investigator Steve Moss, who was at home near Farnborough in Hampshire when he got the call.

Once he'd got over the "stunned disbelief that this had happened again", he quickly joined his colleagues in a police escort up the motorway to Kegworth.

They arrived in the middle of the night with the emergency services still battling to free trapped passengers.

"It was an awful sight," says Moss. "We see a lot of dead bodies in this line of work but it's a bit different to see badly injured survivors. That was pretty sobering."

One of the AAIB's first jobs was to salvage and repair damaged aircraft components and check for pre-existing flaws, such as mechanical or wiring errors.

While they methodically combed the wreckage, the investigation was already coming under political scrutiny.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was at the crash site within hours.

She helped draft in more emergency crews and made sure the team had sufficient resources, but her constant demands for updates added to the investigators' workloads.

Officials from the airline industry were also looking over their shoulders, as were the governments of France and the US, where firms who built the aircraft's components were based.

There was no relief from the press either. Reporters wanted daily briefings as they speculated about the cause of the disaster, and it wasn't long before Captain Hunt was being praised for "averting another Lockerbie".

It was a comforting thought given the death toll on the ground in the Scottish town, where 11 residents died in the burning wreckage.

But investigators already suspected the truth might be less palatable.

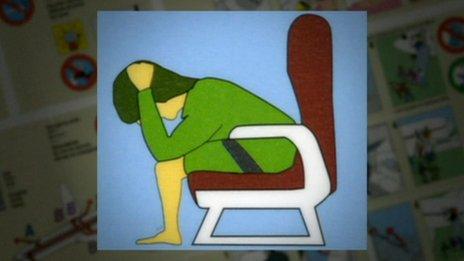

Research following the plane crash on the M1 at Kegworth changed the brace position

From the beginning, it was clear the right engine - unlike the mangled left one - was undamaged. In fact, technicians working for the team were able to get it running again.

However, the plane had been unable to reach the runway - so the working engine must have been switched off before the crash. But why?

Steve Moss was in charge of examining the cockpit instruments.

"We had to check if somehow the right engine's wiring had crossed with the left," he says. "After a few minor repairs we could actually power up the controls again and we were able to rule that out."

The obvious conclusion was pilot error - a theory given more support when McClelland's comments were recovered from the data recorder.

Once this disturbing new theory was revealed, the newspapers were quick to seize on it. The Times minced no words with its headline: "Crew shut down good engine".

It remained only for Captain Hunt and his co-pilot to give their side of the story.

Investigators interviewed a seriously-ill Hunt at his bedside. What he told them painted a picture of confusion and panic.

When the plane first jolted, a vibration alert warned that the left engine was shaking violently.

But for some reason the men didn't use the dial. It's still not clear exactly why.

In Captain Hunt's opinion, this particular instrument was unreliable. He told investigators that, on other planes he'd flown, the vibration dials were generally ignored by pilots.

However, the 737-400 had much-improved, more accurate sensors.

There was also some suggestion the new dials were too small, and difficult to read while the plane was vibrating.

Either way, the crew had to resort to trial and error.

"The [left] engine was surging," says Steve. "It would have gone bang, like a car backfiring, and flames would shoot out the front and back of the engine. That's what was rattling Hunt and McClelland.

"If you can't see from the instruments which engine is having the problem you reduce power to each one in turn."

The pilots chose to throttle back to the right engine - partly, according to Hunt, because of the smoke in the cabin.

In his experience, a Boeing 737's air conditioning system was fed by an intake on the right-hand side of the plane - near the engine.

So logically the flames must also be on the right, with the intake drawing in the smoke.

Again, he was apparently unaware of changes in the new 400-series. They took in air from both sides.

Remarkably though, the plane seemed to settle down.

This, according to the AAIB, was nothing more than an unfortunate coincidence. However, it convinced the pilots they had solved the problem.

During the next few minutes, air traffic controllers said Hunt's workload was "very high", and at some point he decided the best course of action was to completely shut down the right engine.

It was the final, fatal error.

When the damaged left engine failed there was nothing keeping the plane in the air.

In the frantic final few seconds of the flight, as alarms warned they were close to crashing, the men desperately tried to start the engine up again. But it was too late.

In one survivor's words, the jet became like "a stone hurled across a field" - it had forward momentum but ultimately fell to earth.

British Midland pilots Captain Kevin Hunt and First Officer David McClelland

Eighteen months after Kegworth, the AAIB published its report.

It found the engine damage had been caused by a fan blade which had cracked, external and loosened due to fatigue.

As for the pilots, investigators said they had not been given proper training with the recently-redesigned cockpit instruments - in particular the vibration indicators.

But they ultimately decided their responses had been hasty and ill-considered. Both Hunt and McClelland were sacked by British Midland.

Many survivors feel the men were made scapegoats and that British Midland - and the airline industry as a whole - did not shoulder enough of the blame.

In a BBC documentary in 1991, Captain Hunt said: "We were the easy option - the cheap option if you wish. "We made a mistake - we both made mistakes - but the question we would like answered is why we made those mistakes."

Some time after the accident, David McClelland was awarded an out-of-court settlement for unfair dismissal.

A memorial to those who died in the tragedy stands in Kegworth's cemetery. It rests on a bed of soil taken from the crash site

In the 25 years since the crash, Chris Thompson has made a remarkable recovery.

After a couple of years, he managed to fly without self-medicating and he no longer goes through his routine of picturing Flight 92's seating plan before checking in.

He threw himself into the work of the Air Accident Safety Group, which he formed with Alan Johnston. Both campaigned for years.

Their work has led to the implementation of many of the AAIB's 31 recommendations including strengthening of aircraft seats, better testing of aircraft and training of pilots, and changes to the working practices of cabin crew. The brace position was also improved.

"I like to think that after being in the crash I've benefitted. I like to think I'm a better person, but don't we all," Chris says.

Today he is "rational" about air travel and wouldn't think twice about putting his family on a plane - indeed, days before he spoke to the BBC, he flew back from a holiday in Portugal.

Approaching the check-in desk, he wasn't medicated. He hadn't consumed alcohol to get him through the flight. His only concern was getting home on time.

The dead seats were far from his mind.

-

Plane seating plan

×

-

1. Chris Thompson

×Seat 1E

Chris shattered both his legs, but benefitted from then-revolutionary procedures to pin the bones together – partly developed for bomb victims in Northern Ireland. After months in a cage-like contraption, he was moved into a wheelchair and finally –a year after the crash – he could stand up, but had to learn to walk again.

Because of his job, he had no choice but to eventually get back on a plane. He helped establish the Air Accident Safety Group and campaigned to improve standards on airlines. He says he still thinks about the crash, but no longer lets it rule his life

-

2. Dominica McGowan

×Seat 15B, or possibly row 11, 12 or 18

Because Dominica managed free herself from the plane, her injuries were initially assumed to be minor. In fact, as well as a broken back, she had broken all her ribs and a leg, damaged her pelvis, punctured a lung and seriously injured her spleen.

She says her status as a survivor meant everyone wanted to talk to her, which helped her to cope emotionally. Other than back pain – at times severe – she says the crash hasn’t interfered with her life.

“I have always maintained I was so lucky - that really has stayed with me.”

-

3. Alan Johnston

×Seat 17D

Alan insists that, despite his broken bones – including a smashed pelvis – his family suffered far more than he did.

After returning home to the coastal village of Strangford in Northern Ireland, he began to show symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder and “became a different person" with delusional dreams about solving world peace. He received psychological help, and recovered quickly enough to fly again on the first anniversary of the crash.

Along with Chris Thompson, he threw himself into aircraft safety campaigning, and today regards the disaster as one of the most interesting episodes in his life.

-

4. Mervyn Finlay

×Seat 21A

Mervyn was one of the most seriously injured and remembers nothing of the crash itself. He broke his neck and back – his spine was left “hanging by a thread”. He needed months of rehabilitation. To this day he suffers with balance problems, black-outs and permanent pins-and-needles in his feet.

When he first stood up again, after some gruelling physiotherapy, Mervyn says he “could have cried”. He had to give up the job he loved and has never been able to play sport with his son. A fear of flying means he has also missed out on family holidays abroad.

-

5. Stephen McCoy

×Seat unknown

Stephen was just 16 at the time of the crash, returning from his first trip away from home without his parents. He was the most seriously-injured survivor and spent three years in hospital. He still suffers from the effects today.

His sister Yvonne has given up work to become his full-time carer. They live in a specially-built house where CCTV cameras allow the family to keep an eye on Stephen. He recently celebrated his 40th birthday, and the family still hopes for improvements. He is well known at the Roman Catholic shrine at Lourdes in France, where the family makes an annual pilgrimage to pray for a cure.

Audio slideshow produced by Paul Kerley. Infographics by Andreia Paralta Carqueija. Additional reporting by Jim Davis, Namrata Varia and Nick Tarver.

- Published8 January 2014

- Published8 January 2014

- Published8 January 2014

- Published21 December 2013