Ladybird Books: The strange things we learned

- Published

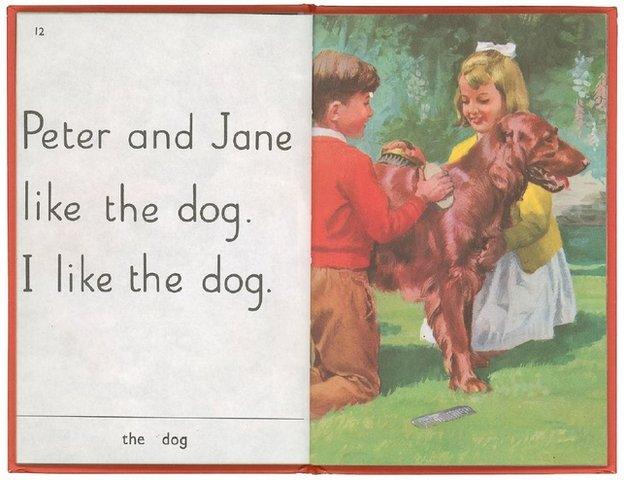

Many children learned to read with Peter and Jane in the Key Words Reading Scheme books

Ladybird Books is celebrating its 100th anniversary. The books delighted children for decades, but what did they teach us and have their lessons stood the test of time?

The brand grew from a small printers in Loughborough, Leicestershire, called Wills & Hepworth, which registered the Ladybird imprint in 1915.

Viewed today the books are striking for the warm and positive view of the world they presented children, says Professor Lawrence Zeegen, who has explored their history.

But some of the illustrations and text seem strange - and even offensive - when viewed through a 21st Century lens.

Women do all the housework

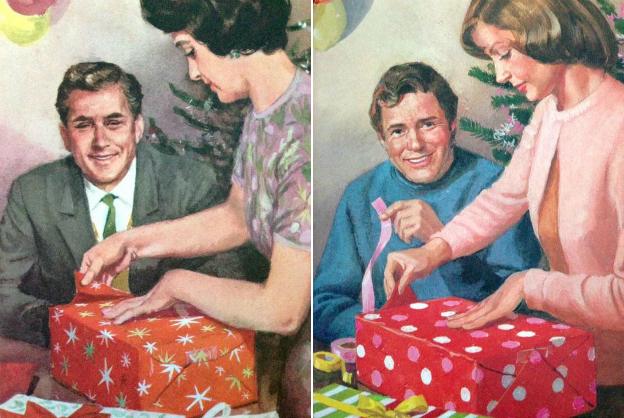

The 1964 illustration of "Mummy wrapping a present" (left) was updated in 1976

In 1964 Ladybird launched its Key Words Reading Scheme, known by many people as "the Peter and Jane books".

"Jane was obviously helping Mummy in the kitchen and Peter was helping Daddy wash and clean the car or working in the garage," says Prof Zeegan, author of a new book called Ladybird by Design, external.

Ladybird was criticised for stereotyping and updated the books in the 1970s.

"In the second generation of books you saw not just Mummy going out to work and being more proactive, you saw Jane doing things that certainly would have been considered ungainly 10 or 15 years before," adds Prof Zeegan.

Jane started wearing jeans instead of dresses, Daddy started doing the washing up, and there was a less overtly gendered approach to Peter and Jane's games.

Helen Day, a Ladybird book enthusiast who has collected at least 10,000 copies, highlights some of the subtle changes by posting before and after images on her Twitter page, external.

"One was a picture of Mummy and Daddy in the 1960s wrapping up Christmas presents, and then when you look at the 1970s version it's almost identical but Daddy is looking engaging and holding up a pink ribbon," she says.

"It's almost the same artwork but there's this tiny difference."

Men do the important work

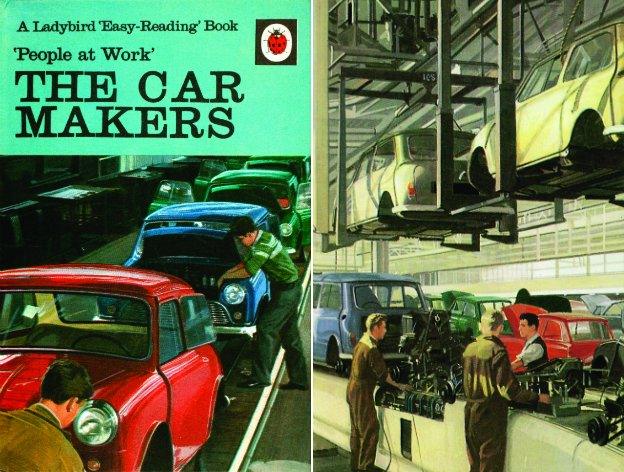

Men did nearly all of the jobs in the 'People at Work' series

Ladybird published a series called People At Work between 1962 and 1973, which Prof Zeegan described as "an absolute time capsule" of jobs from a bygone age.

Men did nearly all of the jobs, with titles including The Fireman, The Policeman, The Farmer, The Postman, The Airman, The Builder and The Soldier.

Ms Day said the exception was a "token" title called The Nurse. In here, we learned that "the doctors tell nurses what to do".

Similarly, in The Customs Officer, we learned that if female customs officers "are not busy, they help with the office work".

Ladybird gradually showed more working women, often referring to them as "girls".

"You can sort of trace the way they are slowly entering," says Ms Day.

"In the 1960s they occasionally do Hoovering up on a sewing line or something, and then you will find the boardroom and there's a woman without bouffant early 1970s hair taking notes when all the men are doing all the work," she says.

"And then a little bit later you have a woman on a commuter train, a sort of career girl."

Only Britain shaped the world

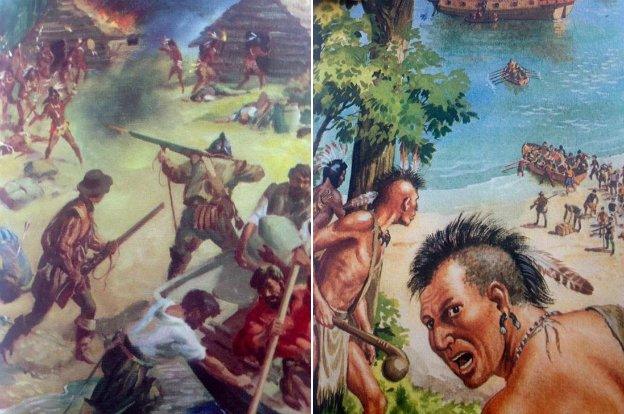

The perspective of the Sir Walter Raleigh book changed between 1957 and 1980

Ladybird's Adventure from History series was published between 1956 and 1981.

Prof Zeegan says the early books were written "very much from a British perspective".

"They were very much from 'the world has been shaped by these really key important British adventurers and explorers and kings and queens and prime ministers etc', and it's fair to say that if you only learnt your history through Ladybird books you had a very British view of the world that pretty much said that Britain had shaped it."

However, the later books recognised the achievements of other nations.

There were also subtle changes to the illustrations, notably Sir Walter Raleigh.

"In the first version of Raleigh we had been with the colonists, seeing the Indians coming out of the wood, and then in the 1980s you see it from the natives' standpoint looking down at the colonisers coming," says Ms Day.

Some of the original text in the history books, written by Lawrence du Garde Peach, was also updated to make it less partisan.

Everyone in Britain is white

A golly was removed from a toyshop window in a later illustration

Some of the Ladybird books were "incredibly white", says Ms Day.

"I've looked through to find out when the first black faces first appear and it's not until the 1960s," she says.

"Despite an influx of immigrants welcomed to the UK to help rebuild Britain after the Second World War, there's no mention of that in Ladybird's world," says Prof Zeegan.

However, he says the books started to become more representative in the early to mid 1970s.

"By the time they were doing this it was probably a little too late to be honest.

"I have to say they never or they rarely take centre stage. They are people in the background."

Ms Day said subtle changes were made to the illustrations in later books, including airbrushing a golly from the window of a toy shop.

"The reason we can now look back at [these books] and say 'Oh my goodness look at that, oh why did they do it that way, oh how funny, how quaint, how politically incorrect, how wrong' is because the books lasted," she adds.

"If it was a teaching manual or something dry and dusty you would have read it in its time, it would have gone into the attic, it would have been chucked away and that would have been it. But these books lasted, and then they got handed down."

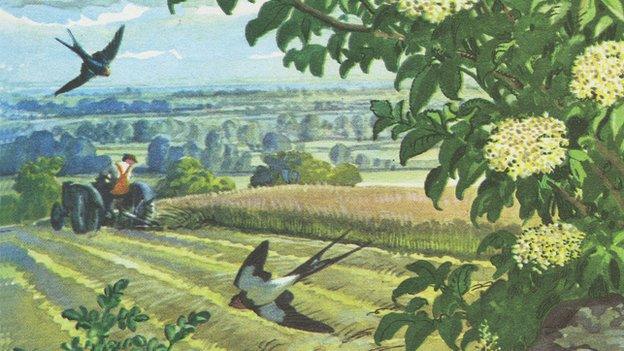

Playing with fire

The activities in the books went beyond today's health and safety norms

Ladybird's science books showed activities including stripping the casing from a battery with pliers, using a penknife to shape wood into a propeller and making fire with a magnifying glass.

In his book, Prof Zeegan says "it is unthinkable that any children's book publisher today would consider promoting activities in the same way".

He has childhood memories of copying a magic trick that involved playing with matches and also remembers burning small insects with a magnifying glass.

"I'm not overly proud of that, but that's the kind of fun and games we had.

"I'm not sure there were any more accidents because of these books, probably not, but certainly nowadays children wouldn't be encouraged, they would probably be positively discouraged from the types of activities that Ladybird featured in this set of books."

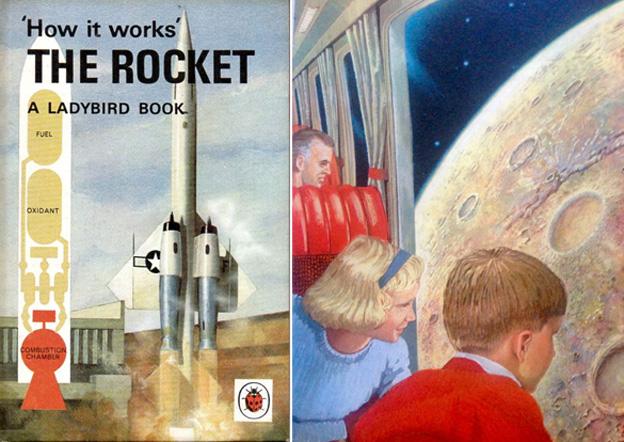

Space tourism

The Rocket, from the 'How it works' series, predicted space travel

Many Ladybird books predicted the way technology would develop.

"It's really fascinating to see their future perspectives then," says Ms Day

"I do love the space ones. So for example the first Exploring Space book was actually done before the moon landings, so they are predicting one day man will land on the moon.

"It says 'Men may land on the moon by 1970'."

Ladybird was correct, but other predictions were less accurate.

"By the time you get to How it works, The Rocket, at the end of that they are predicting space tourism, and it looks like Peter and Jane are looking out of the window at the moon's surface," said Ms Day.

"I remember at school writing essays about what the future would be like in the year 2000, and I remember writing a letter which was pretending to be from my own child who was on a moon base back to me, because you were so sure that by 2000 it was going to be like a Ladybird book."

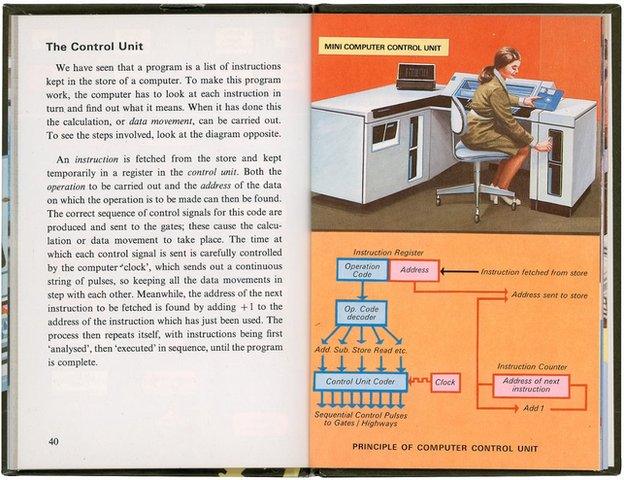

Mini computers are the size of a room

'How it works' The Computer was published in 1971 and updated in 1979

The series 'How it works' had titles as diverse as Television, The Hovercraft and Farm Machinery.

The contents of the books are like time capsules for what technology was once like.

The Motor Car needed updating seven times, as it dated so quickly.

"The computer is a great one because of course there's one particular illustration that depicts a computer the size of a small room, and I think it's described as a small computer for a businessman," says Prof Zeegan.

"It's laughable today, but that's what's quite nice about that world."

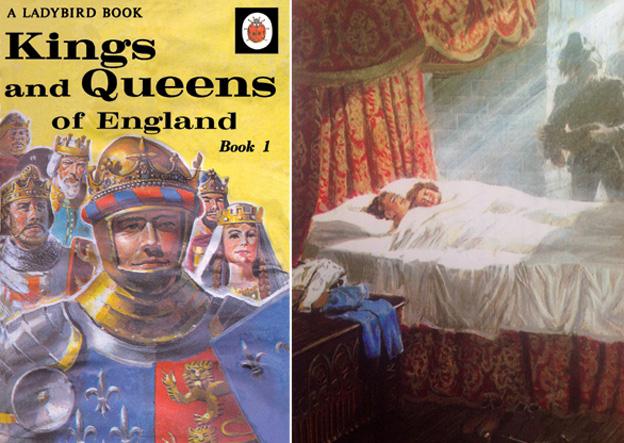

Richard III was bad

The Kings and Queens of England books were completely rewritten and reillustrated in 1986.

Ms Day said the Kings and Queens of England books provoke an angry response from Ricardians on Twitter.

"Richard III has a one-page write-up and if I tweet that picture people get really het up about it," she says.

"If we go to book one you don't have much on Richard III himself but you've got a picture of the Princes in the Tower."

The book states: "Richard had himself crowned as Richard III, and it is probable that the boy king was murdered by his orders. This has never been proved. Fortunately Richard's reign was short."

"There's just a shadowy figure so we don't know who it is. It's a rather scary picture though.

"In the first page of the second book you've got a picture of Bosworth Field and Henry VII being crowned, and he looks sort of dashing and good looking, so they [the Ricardians] get upset about the Tudor rhetoric."

Nuclear power is definitely a good thing

The Story of Nuclear Power and The Story of Medicine were both published in 1972

The Story of Nuclear Power, published in 1972 before accidents such as Chernobyl in 1986, is overwhelmingly positive in its description of nuclear power.

"It's all part of a 1970s optimism, post-war, technology is good, the future is rosy, look at this beautiful artist's impression of Sellafield Power Station with blue, blue skies and happy seagulls," says Ms Day.

The Story of Oil, also from the Achievements series, has a similarly optimistic view, stating: "Oil helps make the deserts fertile."

"There's a picture of deserts with a few sheikhs standing around and little plants, and they are talking about oil being the secret for feeding the world because oil is going to turn the deserts fertile again."

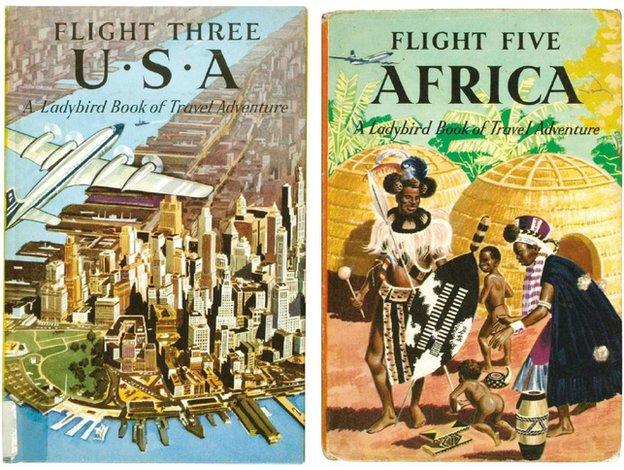

The USA is full of 'Cowboys and Indians'

The Travel Adventure series was published between 1958 and 1962

"Certainly through the 1960s we weren't well travelled, we had a particular view of our place, our standing in the world, we had won the Second World War, and the British Empire was still fairly intact," says Prof Zeegan.

"The colonies were where they were, and we had a rather simple view of our standing in the world, and it's fair to say a rather condescending view of other civilisations."

The Travel Adventure series reflected this.

"This isn't to point a finger at the editorial team, the writers or the illustrators of the early 1960s at Ladybird, because I think Ladybird's view of the rest of the world was one that chimed with public perception.

"Our sense of what the US was like was very much built from Hollywood movies, and you see in the Travel book to the USA depictions of cowboys and what we now know as Native Americans but were termed Red Indians.

"The same is true of the books of Australia, where Aborigines are depicted in a particular way.

"I wouldn't lay the blame at Ladybird's door, I think that Ladybird was reflecting a particular culture and a particular understanding of the rest of the world."

- Published28 June 2014

- Published25 February 2014