The 'wreckologists' digging for World War II aircraft

- Published

Wreckage like this Spitfire fuselage is displayed at Lincolnshire Aviation Heritage Centre

Beneath the green expanse of the British countryside are hundreds - or perhaps thousands - of World War II aircraft.

Despite it being 70 years since the Allied air campaign against Nazi Germany, many of these remains are remarkably well-preserved.

Dave Stubley is one of hundreds of men and women across Britain who spend their free time finding out where the planes crashed, then digging them up.

"It gives you a buzz of excitement, because we never know what's going to be buried," he said.

"We are a funny breed. I don't deny the fact."

Mr Stubley is secretary and "general dogsbody" of Lincolnshire Aircraft Recovery Group (LARG), a voluntary group founded in 1973.

He estimates a couple of thousand aircraft crashed in Lincolnshire - an area which during World War II had so many airfields it became known as Bomber County.

Wreckage was often recovered and recycled, but sometimes an aircraft would hit the ground with such speed that it buried itself.

Of those that crashed, Mr Stubley estimates about 10% are still under the ground.

Remains of 2nd Lt Charles Moritz were accidentally found by the group

"The soil falls back on it and seals it in, so it's a little time capsule in the ground," said Mr Stubley.

"The soil and the oil and the lack of air going to it preserves it. The metal can come out like shining brand new.

"You can even find paperwork because when they leave the aircraft they leave everything behind - they want to parachute to safety."

LARG concentrates on one main dig a year, gathering information from eyewitnesses before the stories are lost forever.

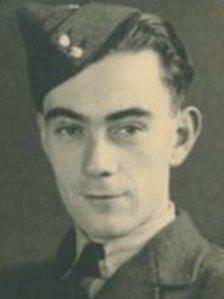

Charles 'Butch' Moritz was given a military funeral in Illinois after his remains were found in Lincolnshire

"The World War II records don't always say what happened," said Mr Stubley.

"There are many books and local people that remember all these crashes and we can research them and go into the area and start talking to the local older generation to see if they remember anything crashing.

"Unfortunately, that generation is dying off, but we might get a farmer's son now working at the farm, and he might know."

Metal detectors are used to narrow the search, and the group has to get permission from landowners - and a licence from the MOD - before digging up fields.

Unlike normal archaeologists, those who hunt for plane wreckage tend to use diggers to get it out of the ground.

For this reason, Mr Stubley said the term "wreckologist" is more appropriate than aviation archaeologist.

Mr Stubley said oil and fuel in the ground helps preserve remains such as this Merlin engine

"It's covered in mud and oil and is all mangled together so there is no way you could dig it with a trowel," he said.

The group has recovered German and US aircraft as well as British.

"You get a lot of German bombers up in Lincolnshire, going to attack, but you won't get any German fighters because they didn't have the range to get up here," said Mr Stubley.

The remains of a Mustang pilot were returned to the US earlier this year after he was discovered by LARG in a field near Faldingworth.

LARG is a member of the British Aviation Archaeological Council (BAAC), and Mr Stubley said members avoided digging sites where there could be bodies.

The MoD does not usually give licences to dig sites with human remains.

"In the case of the Mustang the American records were the wrong way round. That's how we unfortunately found the body," said Mr Stubley.

"As it turns out, the family in America are really happy. It's a conclusion for them; he's accounted for."

Mr Stubley said oil and fuel helped preserve wreckage in the ground

So what happens to wreckage once it has been dug up and cleaned?

"Some people dig up aircraft and sell the bits, which BAAC is totally against," said Mr Stubley.

"It's part of our ethics that you can't be making money from people's death."

Last year there were reports souvenir hunters, external had trawled the field in Dorset where Red Arrows pilot Flt Lt Jon Egging died.

Thanks to LARG, Joseph Bannan's widow found out where her husband died

One man reportedly intended to sell wreckage on eBay.

"There are some rather unscrupulous people and they've got no ethics," said Mr Stubley.

LARG displays much of its recovered wreckage at Lincolnshire Aviation Heritage Centre, and some has been given to other museums.

"A lot of the groups have got a small museum that they have set up," said Mr Stubley.

"Some do mobile displays or put the displays in a library.

"If we discover an aircraft where someone was killed we try to remember them in the best possible way, with a plaque or whatever. It's all part of remembering modern history."

One such memorial is at Bicker, near Spalding, where a Lancaster crashed.

LARG cannot dig the site because the crew might be there, but the grandson of one of the crew members, Flt Sgt Joseph Bannan, found details of the memorial on the internet.

As a result, the crew member's widow, now 92, was able to visit the site, external thought to be her husband's grave for the first time.

Her daughter, Jo Maddox, was in tears when she first spoke to Mr Stubley on the telephone.

Relatives of Flt Sgt Joseph Bannan visit the memorial in Bicker every year

"My mother was pregnant with me when my father was killed and all she ever knew is it was in England," she said.

"You were just given a telegram saying 'missing believed killed'."

The Protection of Military Remains Act 1986, external prevents recovery groups from contacting relatives of those killed, but families often come forward themselves seeking information.

BAAC is now working on a database of crash sites which will be available to the public, and this could help more people find out about how their relatives died.

Finding out about Joseph Bannan's death has been important for his family, who now visit the memorial every year.

"We were told there were fuselage bits in the field, churned up, and my grandchildren ran through the field and picked some up as souvenirs," said Ms Maddox.

"I'm so grateful to those people of Bicker and to Dave."

- Published18 May 2012

- Published4 May 2012

- Published31 August 2011

- Published26 April 2011