Dambusters: Death and glory

- Published

Crews had little more than six weeks to practise low level attacks over water at precise speeds and heights

The experimental four-tonne bomb had to be dropped at the right height, at the right speed, at exactly the right distance from the target, to allow it to achieve the improbable feat of skipping across water.

It had to be carried in specially adapted planes, across occupied Europe, at night, by a squadron formed just eight weeks earlier.

And, of course, the dams had to break.

While the dams and reservoirs of the Ruhr valley, which fed the industrial powerhouse of the Nazi state, had been identified as possible targets in the late 1930s, and noted engineer Barnes Wallis had been developing a suitable bomb since 1940, Operation Chastise was essentially a frantic race against time.

The right combination of highest water levels and full moon, to make the attacks theoretically feasible, happened in mid May. Full authorisation had been given in February.

Frantic testing of the Upkeep bomb showed it had to be dropped from 60ft (18.2m)

The squadron - 617 - was formed on 21 March but crews came in for days afterwards.

Official 617 Squadron historian Robert Owen said: "The crews had about six weeks to train in night-time low-level flying and navigation with only the sketchiest idea of what the mission was.

"But also AVRO, which made the Lancaster, had only slightly longer to modify the planes to carry a huge bomb which was still being developed.

"And of course Barnes Wallis and his team had to make Upkeep (the bomb's codename) work."

The first live Upkeep was tested from a Lancaster on 13 May, just three days before the raid began. The last major training exercise was on 14 May and the final aircraft was delivered on the afternoon of the operation.

The first of 19 Lancasters took off from RAF Scampton, Lincolnshire, at 21:28 on 16 May.

They flew at treetop height to avoid radar, with the attacks going in during the early hours of 17 May.

On the morning of 17 May, RAF photographs showed breaches in two dams

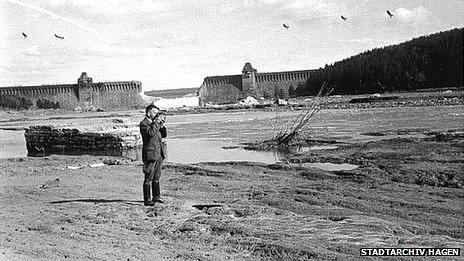

Most of the casualties and damage was suffered below the Mohne Dam

Flood waters surged down the valleys cutting road and rail links

Rescue efforts efforts began immediately and continued for hours

Mud, debris and dead animals hampered rescue efforts and polluted water

Among all the achievements behind the raid, Mr Owen selected one for the highest praise.

"Airmanship," he said. "You are asking twentysomethings to fly an aircraft weighing over 63,000 lbs, about 30 tonnes, physically, no power controls, haul it around the sky at 100ft all the way into Germany and back, sitting on that one seat for six hours or so.

"We have all driven down the motorway for three hours and you know what that feels like - and that is without being shot at."

Of the four dams targeted, the Eder had the most difficult approach.

Teenage defender

Dambuster pilot David Shannon described the problems of his attack: "There was this huge gothic castle stuck up like an eagle's nest right up on a point and you had to fly over that and drop right down the hill.

"It was wooded and rough land and scenically it was rather beautiful, the situation of this lake, but not the sort of place to try and get in with a four-engine aircraft, down to 60ft, do your run, get your speed to 232mph and then have a sheer rock face at the end of it to climb up over the top."

While the Eder was undefended, the Mohne was surrounded by guns.

Beside one, facing the onslaught, was Karl Schütte, a teenage army reservist.

Some anti-aircraft guns at the Mohne were crewed by teenage reservists

In an interview with German broadcaster WDR in 1993, he said: "And then the fifth aircraft came along. They perhaps had the easier task. Then two other monstrous planes came flying over, to guide them through our fire.

"They came frighteningly quickly towards the dam and were so close to it that even today, I can remember looking the pilot in the eyes.

"In a panic, we reached for our weapons and began to shoot. It was almost comical but at that moment, you forget the danger you are in.

"And then Lake Mohne began to shake and the next moment, I looked down and saw the dam had been breached."

Water's fury

The experimental bomb, the new squadron and the bold plan had worked. A torrent had been unleashed. But at a cost.

Of the 133 aircrew taking part, 53 died and three were captured.

Extensive damage was caused on the ground - though the impact on the wider German war effort is still hotly debated.

Estimates of the civilian death toll vary between 1,200 and 1,600, with Germans and foreign prisoners sharing the brunt of the water's fury.

Witnesses said the shock of the attack and force of the water was overwhelming

Elizabeth Müller, who lived in nearby Neheim and was expecting her first child, remembered: "We were fast asleep when we heard a huge, thunderous noise.

"We looked out at the dam, which was lit up, and then there was a terrible bang. As we ran outside, there were shards of debris and bits of the window on the ground.

"Then the water rose and rose.

"Our house was flooded but remained standing while everything else, trees, roads, gardens, was swept away."

Also in the path of the deluge were forced labour camps. One inmate was Russian Antonia Ivanovna,

She said: "Suddenly there was lots of noise. People were screaming and we knew we had to get out of there. I ran across the camp with my sister, past people locked in their blocks. We ran to the road into town - we knew the way as we had to use it every day.

"Suddenly my sister fell to the ground and she was bleeding. She told me to save myself, leave her but we carried on together.

News of the raid came while Winston Churchill was in Washington to discuss the future of the war

"It was terrifying, foggy and cold. We had taken our bed sheets with us but we didn't have much on, the water came up as high as our backs.

"On the way out, a German woman grabbed my arm tightly. I never saw her again, it was an awful moment."

Antonia and her sister survived the night but had to wait until late evening until the authorities corralled them into an old theatre and gave them food.

"What did we do? We had to look for the bodies in the mud. We washed their faces and they were photographed.

"The German corpses were taken to the church. The Russians were put on to a wagon and taken to a mass grave.

"For two to three months we kept finding bodies - they had become fat and swollen with the water. It was awful. I'm sure lots of Russians ended up in German graves and Germans in Russian ones."

Around the world, news of the attacks spread to front pages and radio bulletins. Claim and counter-claim were made about the damage and number of deaths.

In Washington for crucial negotiations, Winston Churchill basked in what he called a "gallant operation" causing "unparalleled devastation".

A legend was born.

- Published16 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013

- Published16 May 2013

- Published15 May 2013