Will a ban on public use of legal highs in Lincoln work?

- Published

A ban on people using legal highs in Lincoln city centre is set to be introduced. But how much of a problem are these stimulants, and how effective can the ban be?

Thousands of tourists visit the picturesque cathedral city every year, but council bosses are concerned it has been attracting a different type of visitor in recent times.

Lincoln has become well-known for having "a ready and cheap supply" of legal highs, according to a council report, external, leading to what the authorities describe as "legal high tourism".

Across the wider county, police recorded 820 incidents in 2014 where the term "legal highs" had been logged.

This was a significant increase from 2011, when there were just seven, and was more than any other police force area that provided figures for the research by the Centre for Social Justice, external.

The City of Lincoln Council says legal highs have caused considerable anti-social behaviour problems and it is to introduce a ban it hopes will tackle the problem.

It wants to use a Public Space Protection Order (PSPO) - a new type of power introduced by the government to deal with anti-social behaviour.

What are legal highs?

Research by think tank the Centre for Social Justice, external revealed that in England, the number of incidents involving a legal high rose from 1,365 in 2013 to 3,664 in 2014, an increase of 169%

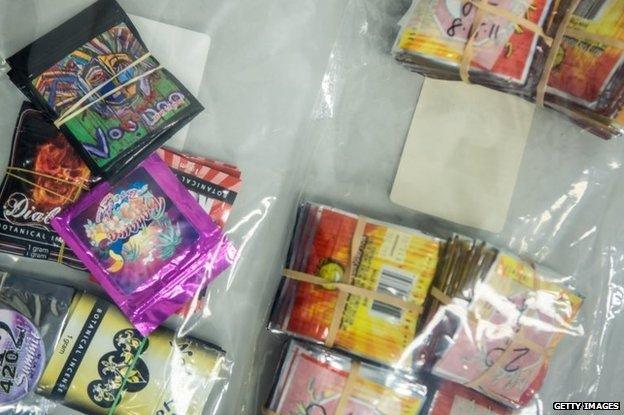

Legal highs are similar to illegal drugs but have had their chemistry tweaked meaning they are not covered by the Misuse of Drugs Act and are legal to sell

Some, such as Spice, are equivalent to highly potent cannabis, while others are designed to imitate drugs like LSD or even heroin

Because they are not covered by the law they can be sold openly; normally in "head shops" though also in places such as garages and petrol stations

Marked "not-for-human-consumption", they are packaged like sweets and labelled "research chemicals" or "plant food"

Sam Barstow, the city's manager for public protection and anti-social behaviour, said the order would prohibit people from using "intoxicating substances" in the city centre.

"The whole driver behind this for us has been about taking a proactive stance and trying to do something innovative to tackle an issue that's really having an impact on people that live locally, people that work locally and people that might want to come and visit our city centre," he said.

"Intoxicating substances" includes alcohol and legal highs, but the order only applies to public places.

Therefore, people will still be able to buy legal highs in Lincoln and take them home to use.

The council said it does not have the skills or resources to enforce the order so on-street enforcement will be the job of Lincolnshire Police.

Legal highs are sold in colourful wrappers, looking similar to sweet packets

Insp Pat Coates, neighbourhood policing inspector for the city centre, said he fully supported the council's action but he believed the measures do not go far enough.

"It tackles the on-street problem of legal high usage and the anti-social behaviour that we've seen as a consequence of that," he said.

"We would like to see better legislation to enable us to deal with the actual sellers.

"It doesn't tackle the selling of the products actually at the shops so we want to see further action being taken against those shops."

The BBC visited Head Candy, a "head shop" in Lincoln that openly sells legal highs.

Staff said they did not want to comment because they felt the shop had been misrepresented in a previous newspaper interview.

However, customers said that shop staff were trying to make a living from a legitimate business, and argued that legal highs do not cause as many problems as people excessively drinking alcohol.

Insp Pat Coates said legal highs cause similar problems to street drinking

But Insp Coates disagreed, saying: "What we've seen is threatening behaviour, people being aggressive, shouting.

"We are seeing issues with people collapsed in the street under the influence and people behaving very erratically.

"I liken it a lot to street drinking."

Rupert Oldham-Reid, a senior researcher at the Centre for Social Justice, said people underestimate the dangers of legal highs, also known as "new psychoactive substances" (NPS).

"Last year we found that the number of people in addiction treatment for taking NPS jumped 216% in England in the last five years," he said.

"Tragically, in Scotland alone there were 113 deaths related to legal highs in 2013.

"As ever, it is the most vulnerable in society that are suffering from the increased supply of these drugs, with strong drugs available for pocket money prices.

"Sadly young people report that their legality and high-street availability means some think they are safe."

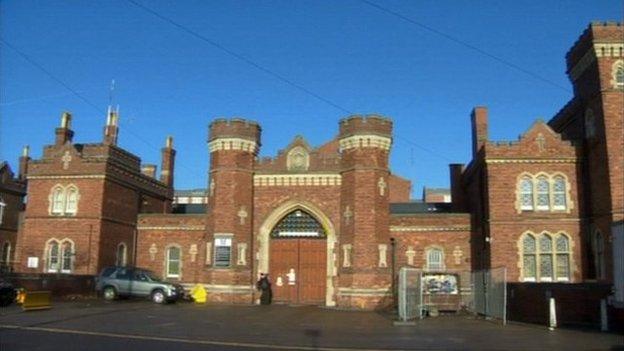

The governor of Lincoln Prison said legal highs are a growing problem among prisoners

Lincoln's problems with legal highs are not just restricted to the streets, according to the governor of Lincoln Prison.

Peter Wright said the use of such drugs is a growing problem and has caused some inmates to become "grotesquely violent".

The Ministry of Justice has announced that prisons are being given more powers, external to deal with the increasing "phenomenon" of legal highs.

In Ireland, the government has already introduced a ban on the sale of psychoactive substances, with the exception of substances such as tobacco and prescription medicines.

The Centre for Social Justice believes the UK government should do the same.

"We spoke to doctors in A&E units across Ireland and the reaction was overwhelmingly positive," said Mr Oldham-Reid.

"Before the ban, young people were increasingly being admitted with psychotic episodes, heart failure and injuries related to their NPS use."

Insp Coates thinks legislation could help in Lincoln too.

"There does need to be a change to current legislation if we are going to really effectively tackle the problem," he said.

- Published19 January 2015

- Published29 January 2015

- Published15 October 2014