World War One: The symbolic reunion of five brothers killed in action

- Published

The Beechey brothers, from left to right: Harold, Charles, Frank, Barnard and Leonard

Even by the standards of that bloodiest of wars, Amy Beechey's suffering was extreme: five of her eight sons would not live to see the end of World War One. A century on, stone crosses have been erected across the world in a symbolic effort to reunite the five brothers.

Even for the time, the Beechey family was a big one. Amy, the wife of a country vicar, had eight sons and six daughters.

All eight boys would serve in World War One.

Amy lost five of those eight sons - and one of the survivors she never saw again. It was a loss she was not prepared to take quietly.

When she was presented to King George V and Queen Mary in April 1918, the Queen thanked her for her sacrifice.

She replied: "It was no sacrifice, Ma'am - I did not given them willingly."

Amy Beechey lived in fear of the latest telegram bearing dreadful news

By the time war broke out, the family had moved from the Lincolnshire hamlet of Friesthorpe to a terraced house at 14 Avondale Street in Lincoln, where the city's cathedral was a constant presence.

Each time the postman called, Amy hoped for good news. But more than anything she feared the message that began: "It is my painful duty to inform you…"

The many letters and telegrams sent to Avondale Street that survive trace the devastating impact of the war on the family.

In recognition of their sacrifice, crosses for the fallen five sons have been crafted from Lincoln Cathedral limestone and placed at locations around the world, from Europe to east Africa and Australia.

The Beechey family outside the vicarage where they lived until the Rev Prince William Reeve Beechey was diagnosed with cancer. He died in 1912, leaving his wife to face the war alone

Harold - The Anzac

Anzac Harold Beechey suffered more than most during the war - his cross has been placed at the Anglican Cathedral in Perth, Australia

The nickname for a Lincolnshire native is a yellowbelly - but L/Cpl Harold Beechey was no coward.

Amy's seventh son emigrated to Australia with his brother Chris to make a life as a farmer but after his harvest failed because of a drought, he ended up training as an Anzac in Egypt and fighting in Gallipoli in 1915.

Harold overcame illness and mortal danger, battling Turkish forces in hand-to-hand combat at the same time as fighting dysentery.

He was sent back to Egypt in 1916 and then to France that summer.

His family must have thought he was a survivor when he wrote home from the Western Front in August:

"Very lucky - nice round shrapnel through arm and chest but did not penetrate ribs. Arm not out of action hardly at all."

After just a few months' recovery, Harold was back in France for a freezing winter, which he described in a letter as "pretty gruelling".

His luck finally ran out in April 1917 when he was hit by a so-called "whizz-bang" shell in the trenches, aged 26.

The cross for Harold Beechey has been placed in his adopted home of Western Australia, in Perth's Anglican Cathedral.

Charles - The naturalist

Charles Beechey, who is buried at the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery in Dar es Salaam, was a keen naturalist and hoped to bring specimens back home from Africa

Charles Beechey, known to everyone in the family as Char, was Amy's second son.

He had a successful career as a schoolteacher, but by 1916 was in the trenches in France and by Christmas that year he was in hospital with kidney disease.

He heard of the deaths of two of his brothers while recovering and wrote a letter of bitter disappointment to his mother back in Lincoln.

"I do not think many families have done more for the country than we have," he wrote.

A few weeks later Charles, a private, was on board a ship heading for eastern Africa - in what is now Tanzania - where a fierce battle raged with Germany.

Charles, a keen naturalist, was excited by the wildlife in his exotic new home.

He wrote in September 1917: "The butterflies here are most beautiful and varied - I hope I shall be able to bring a few of the best home to show you."

But only a month later Amy received a letter containing the devastating news that he had been hit in the chest and there was "little hope".

Charles Beechey died aged 39 a few days later. He is buried in a war cemetery in Dar es Salaam, where his cross has been placed.

Frank - The cricketer

Before the war Frank Beechey played as a wicketkeeper for Lincolnshire

As well as eight sons, Amy Beechey had six daughters, five of whom survived into adulthood.

Their favourite brother was Frank, who loved motorcycles and was a keen sportsman, playing cricket for Lincolnshire.

A teacher, he joined up in 1914 and was sent to the front in May 1916 as a signaller.

Frank's work was repairing the telephone cables that provided communication between trenches.

In November 1916 a telegram arrived in Lincoln from the War Office.

Frank, a 2nd lieutenant, had crawled out into no-man's land on a foggy night when his officers lost contact with their troops. He was hit in both legs.

His commanding officer wrote to Amy: "Your son volunteered to take out a telephone wire and telephone.

"He had not gone far in this gallant attempt before he was hit. He must have been suffering a great deal but he would not show it."

Frank Beechey died of his wounds the next day, aged 30, and was buried in a French war cemetery, where his cross has been placed.

Barnard - The eldest

Barnard Beechey regularly wrote home to his mother from the trenches

A gifted mathematician, Barnard Beechey was another brother who worked as a teacher before the war.

Sgt Beechey, who spent the war in France, was one of the keenest letter-writers of the eight brothers.

Barnard's descriptions of life in the trenches are also some of the most detailed.

He wrote to his mother in September 1915: "I have just come out of the trenches, we were in three days and it rained most of the time.

"The experience is interesting and, in normal times when nothing much is going on, quite harmless."

Such a matter-of-fact letter may have been some comfort to his family at home - but it was not long before news of Barnard's death arrived. He was killed in action on 25 September at the Battle of Loos.

For the first time, Amy would read the devastating words: "It is my painful duty to inform you" - a message with which she would become very familiar.

There is no marked grave for Barnard Beechey, Amy's eldest son. His cross has been laid on the grave of a Lincolnshire soldier "known only unto God" in a French war cemetery.

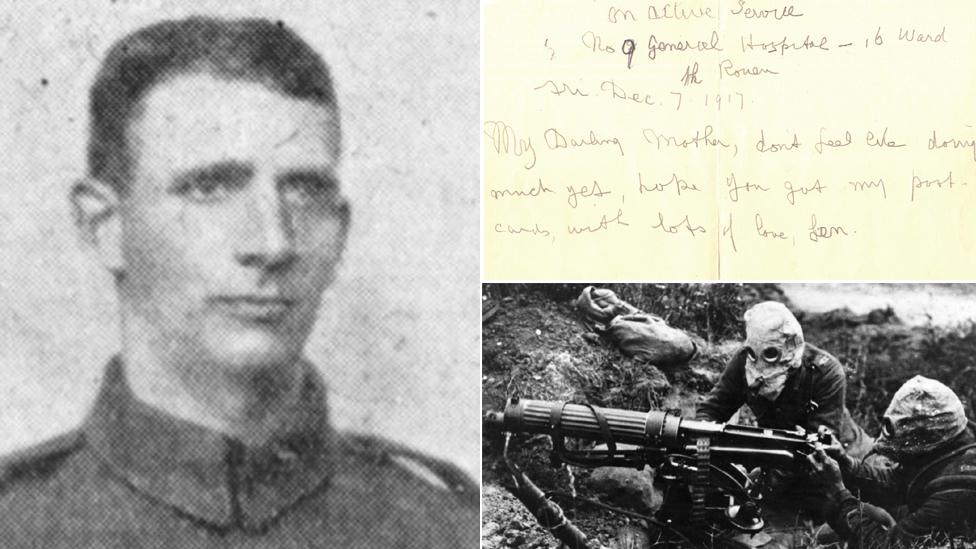

Leonard - The railway clerk

Leonard Beechey left behind a steady job to fight in the war

Leonard Beechey was described as studious by his family. He was the boy who "never got into scrapes".

He was working as one of some 2,000 clerks in an office at London's Euston station when the war began.

When he signed up in 1916 he was 35 - some of his comrades in the London Irish Rifles were almost half his age.

By Christmas that year Leonard was in France and for the next year was in and out of the trenches.

During 1917 his letters were full of questions about his brothers.

After learning of the death of Charles, he wrote to his mother: "It is very difficult for me to realise he is gone - each one seems a harder blow than the previous one. I wish I could see you."

Leonard never managed that. Shortly after, he was gassed close to the French city of Rouen.

The effects of what happened can be seen in a scrawled letter written as he lay dying. He succumbed to effects of poison gas on 29 December 1917, aged 36.

Rifleman Leonard Beechey's cross has been placed in the nearby cemetery where he was buried.

The survivors

A final cross has been placed in the church in Friesthorpe - the hamlet where the family grew up - to mark Amy Beechey's bravery and for her children who survived

At the end of the war Amy Beechey was left to console and lead a family that had endured an extraordinary amount of suffering.

Her youngest son Sam had joined up in the last few months of the war and the junior gunnery officer was sent to France - a terrible worry for a mother who had already lost five sons.

But he returned unscathed. Her fourth son Chris had also been an Anzac, having emigrated with his brother Harold.

Chris, a private, was a stretcher-bearer in Gallipoli and was badly injured in a fall from a cliff. He was sent back to Australia where he lived with life-changing injuries until the age of 85.

Amy never saw him again.

Her sixth son Eric never saw active service, spending the war as a dental technician, first in Malta and later in Greece. He felt the loss of his brothers keenly.

A letter to his mother sent in July 1917 sums it up.

"I know how you feel losing such fine boys as my brothers and continually wondering if the same fate is for any more of us.

"Yet they died men and your name is firmly fixed amongst the roll of brave mothers who have given their sons to the nation."

One of the limestone crosses crafted by masons at Lincoln Cathedral to honour the brothers