Government urged to tackle 'witchcraft belief' child abuse

- Published

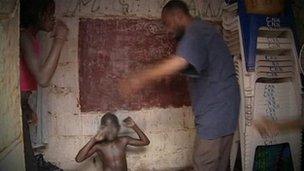

Charity Africans Unite Against Child Abuse works with church leaders to improve their practices

"We're quite happy to talk about what is inappropriate belief when it comes to terrorism or paedophilia," said African studies expert Dr Richard Hoskins.

"But when it comes to fundamentalist religious belief affecting child protection, we don't seem to want to talk about it."

Dr Hoskins, who gave evidence at the trial of a couple who have been convicted for brutally torturing and killing a teenager in their east London flat, is among experts and charities calling for more to be done to tackle the problem of child abuse linked to witchcraft.

Eric Bikubi, 28, and Magalie Bamu, 29, from Newham, east London, have been found guilty at the Old Bailey of killing 15-year-old Kristy Bamu on Christmas Day 2010.

"What happened to Kristy is horrendous and scandalous," said Dr Hoskins.

"We've got to take action because I'd hate to think a child in our capital goes through anything like this ever again."

Scotland Yard said it had conducted 83 investigations into faith-based child abuse in the past decade. They include other high-profile cases such as Victoria Climbie in 2000 and the headless torso of "Adam", a five or six-year-old boy, which was found in the Thames in 2001.

'Ferocious onslaught'

Child abuse linked to belief in witchcraft is a growing phenomenon, according to evidence submitted to the Commons Select Committee's current inquiry into child protection. The government has said it is due to publish an action plan to tackle faith-based child abuse later this year.

In 2010 Unicef reported 20,000 children accused of witchcraft were living on the streets of Kinshasa

Bikubi and Bamu were originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, where witchcraft - called Kindoki - is practised in some churches.

In 2010 Unicef reported 20,000 children accused of witchcraft were living on the streets of DR Congo capital Kinshasa.

However, Dr Hoskins said the Newham incident went way beyond any accepted practices in the DR Congo.

"What happened in the flat was feral," he said.

"It was the most ferocious onslaught.

"It's pretty inconceivable two people could do that for five days in Kinshasa - there is a community glue in place.

"But in London it is very easy to be anonymous and hidden."

The police investigation found Bikubi visited a number of African churches in north London.

'Rogue churches'

Debbie Ariyo, the head of the charity Africans Unite Against Child Abuse (Afruca), said a belief in witchcraft in the UK was "endorsed by various African churches, putting children at risk".

"If you look at how fast new African churches have grown since 2005, it's quite astonishing," she said.

"One of the key beliefs of these churches is in witches and exorcising them."

She said Afruca had worked with dozens of churches to improve their policies and practices.

"But we have churches who preach witchcraft - and this can lead to inciting people to harm children," she added.

"Dozens of rogue churches don't want to change their practices. Small churches can be hidden away in a living room or a garage."

Some churches are held in public centres, including leisure centres and school halls, and "no-one knows what's going on," she added.

Ms Ariyo said financial profit motivated some of these churches.

"The idea is to extort money from parents because if your child is branded a witch you will need to exorcise that child," she said.

There is currently no obligation for faith organisations to register with the Charity Commission or any other organisation in the UK, something which Ms Ariyo said needed changing.

However, the government said regulation would not change the behaviour of such churches and it was working with "faith and community leaders" and child protection charities to "improve awareness and understanding in different faiths and communities about child safeguarding".

Afruca has also been campaigning to prosecute those who verbally brand children as witches.

'Lack of training'

Dr Hoskins said he agreed this should happen.

Kristy Bamu was visiting London from Paris during the Christmas holidays

"When the first prosecution happens because someone is being accused of telling a child they're possessed, then we'll know action's happening," he added.

"For every case that we hear about there are at least 10 others," he said.

Ms Ariyo said there was a "lack of adequate training for police officers" to detect these abuse cases.

Scotland Yard set up Project Violet in 2004 to tackle faith-related child abuse.

Det Supt Terry Sharpe, who heads the project, said they knew it was an "under-reported crime" and the Metropolitan Police would be training officers better over such issues.

"Officers are now encouraged to consider not just the immediate family, but also the extended family and wider faith, culture or community links," he added.

However, some campaigners said they believed the fundamental problem was that politicians did not want to tackle the issue because they thought it would be too racially sensitive.

"There isn't the commitment by the government to bring this thing wide open," said John Azah, chairman of the British Federation of Race Equality Councils.

"They are too scared of being accused of racism."

The Department for Education (DfE) insisted it was a matter it was taking seriously.

A spokeswoman said: "Over the past year, voluntary, faith and community organisations, the Metropolitan Police, Association of Directors of Children's Services and the London Safeguarding Children Board have been working with the government on proposals to tackle faith-based child abuse.

"The proposals will be shared with a wider group of professionals, voluntary sector organisations, faith and community groups to build on what has been developed so far."

- Published24 January 2012

- Published19 January 2012

- Published13 January 2012

- Published12 January 2012

- Published10 January 2012

- Published6 January 2012