Tube 150th anniversary: How navvies paved way for Crossrail

- Published

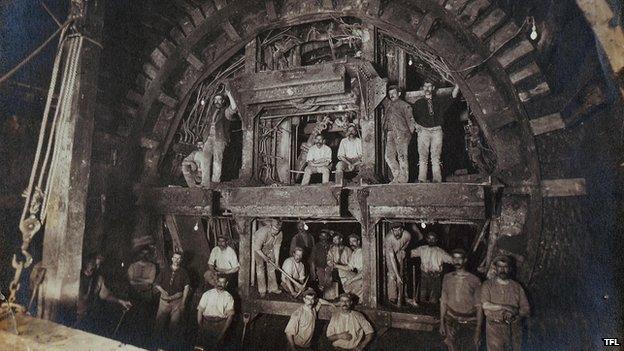

The shield offered workers some protection but conditions underground were still extremely dangerous

One was hand dug by an army of men bearing shovels and spades working deep underground in high-risk conditions.

The other boasts giant machines worth millions of pounds that bore deep below modern-day London.

Yet although 150 years separates them, the construction techniques used by the navvies and labourers who dug the Tube are at the heart of the capital's next-generation underground railway.

Work on Crossrail's 26 miles (42km) of tunnels, which will create a £15bn east-west underground link, began in March 2012.

Construction of the Metropolitan Railway - the world's first underground railway which later grew to be the Tube as we know it - represented a similar feat of engineering for its time.

Work began in March 1860 at a time when improvements in transport were desperately needed as the streets of the world's largest city had become congested with traffic.

'Enormous upheaval'

Early labour-intensive "cut and cover" techniques soon gave way to a technique named "the shield", as engineers looked to build tunnels deep beneath Victorian London.

Transport for London's design and heritage manager, Mike Ashworth, said: "The cut and cover method was to dig a trench, build back the side and roof it over."

It was a simplistic approach to tunnel building, with work happening just below the surface, Mr Ashworth said.

"There was so much disruption caused by demolition through a very crowded city.

Early cut and cover techniques were extremely disruptive as buildings were flattened and utilities ripped up

"Most roads were already full of gas mains and other utilities and there would have been enormous upheaval as they had to shut roads."

When Tube engineers adopted the more successful shield method it heralded the transformation of London's transport network which now serves 270 stations on a service spanning 250 miles (402km).

Mr Ashworth said: "It is highly unlikely that our system would have developed to such an extent if it hadn't left cut and cover."

The shield, which was the technique used as the Underground expanded, was first successfully used in 1825 to excavate what is now the Wapping - Rotherhithe tunnel, which was one of the first underwater tunnels in the world.

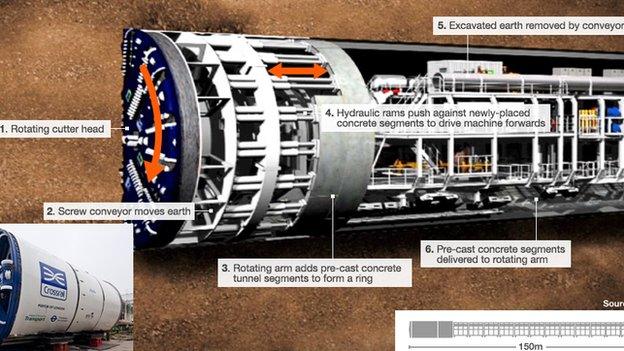

Modifications by James Greathead and mechanised forms of the shield helped form the basis of Crossrail's tunnel boring machines (TBM).

At the front of the original design there was an iron frame and within each pocket was a man with a spade.

Once each section was dug out, timbers were put up to support the earth before hydraulic jacks pushed the frame forward and a row of bricks was built inside the tunnel they had created.

But Tim Shields, curator at London Transport Museum, said: "The shield offered the workers some protection but it would have been claustrophobic and very hot.

"They would often have been bare-chested but some pictures show them working in a jacket and shirt which is quite surprising."

Andy Alder, project manager at Crossrail for the western tunnels, explained: "It was called the shield because it shields the men from the ground.

At top speed Crossrail's enormous tunnel boring machines can chew through 200m of earth every week

"The story goes that it is based on observing how worms bore through wood and this was pretty much the foundation for the main tunnelling work we are doing.

"All we've done is put a steel rotating cutter head with a motor at the front.

"There's still then men digging, the jacks are still the same, then building the precast concrete sections behind and we have a railway that takes the ground out."

But technological advances mean eight TBMs worth about £10m each and a fully mechanised support system allows the construction of Crossrail, currently Europe's largest civil engineering project, to progress at an average rate of about 100m (328ft) every week.

In contrast, the Tower Subway was built to test out the Barlow/Greathead shield technique in 1869/70 at a rate of about 11m (40ft) a week.

Mr Alder said the men digging the Tube could make the same progress in a year that the team behind Crossrail make in a week.

"The technology has come through but what we have done is mechanised it, made it safer, faster and relatively cheaper."

While relatively cheap labour would have seen thousands working to build Tube tunnels, there are just 20 working in the Crossrail tunnel at any one time.

"Health and safety was radically different in extremes of how people worked and industrial injuries far more common and there was no NHS if you were injured," TfL's Mr Ashworth said.

Crossrail's Mr Alder said: "If a few people got killed on a construction site it was part of life but any minor injury is not acceptable for us."

Clay beneath London made for ideal tunnelling conditions, defining the boundary of the Tube, which mostly stays away from the south and east of the Thames.

While Crossrail's TBMs are able to forge ahead regardless of geology, they face the challenge of not being the first to dig beneath London.

Mr Alder said: "We are very much driven by the London Underground map.

"We have to tunnel underneath existing Tube lines, above the Jubilee Line and weave our way around the foundations of big buildings whereas 100 years ago that wasn't the case."