Clapham rail disaster: Ex-firefighter remembers train crash

- Published

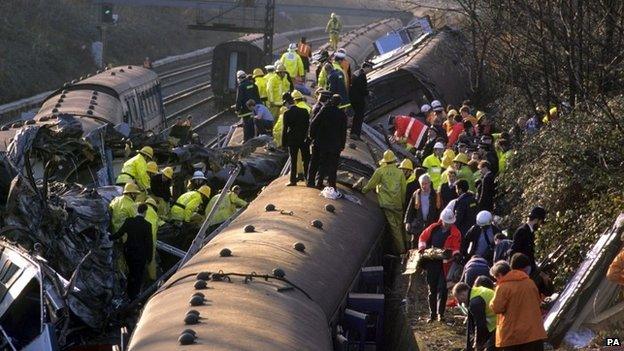

Twenty-five years ago 35 people were killed and 500 people injured when three trains collided in Clapham, south London. BBC producer Clifford Thompson, who at that time worked as a firefighter and was on duty, says he will never forget what he saw. This is his story.

The teleprinter furiously spat out messages printed on to a roll of paper.

It was Monday, 12 December 1988 - a bright but fiercely cold day - just after 08:00.

The London Fire Brigade's Green Watch firefighters were coming to the end of their 48-hour shift.

I stood in the watch room at Stratford fire station in east London - I'd been a firefighter for three years and was one of the Red Watch crews preparing to relieve our colleagues.

We crowded around the teleprinter as messages were relayed from Spencer Park in Clapham.

The crash involved a train travelling from Poole in Dorset

"This is a major incident - initiate major incident procedure," followed by: "two commuter trains in collision, five carriages involved, approximately 150 casualties, unknown number of people trapped, efforts being made to release".

A train travelling from Poole, Dorset, had passed a "clear" signal just outside Clapham Junction Station and hit the back of a train from Basingstoke, ripping open carriages. Some de-railed carriages were pushed into the path of a third train travelling away from London.

Fifteen fire engines from closer stations headed straight to the crash site, along with a number of specialist rescue firefighters and police, ambulance and hospital surgical teams.

At that point - being 12 miles away and a 45-minute drive from Clapham - I thought there was little chance of our crew getting called there.

Then at 10:25 the officer in charge of the incident sent the radio message: "request 18 pump relief... as soon as possible... rendezvous at junction of Windmill Road and Spencer Park."

A few minutes later the teleprinter bell sounded at Stratford and our engine was despatched to the crash.

I was struck by the scale of what met us - there were dozens of emergency service vehicles and also TV crews.

It was a surreal sight, like a massive film set.

We were told to go down to the crash site and assist with the remaining victims.

In the eerie quiet, it was clear that of those remaining, none was alive.

I walked down the steep embankment - at the bottom was a ledge with a vertical drop about 15ft (4.5m) into the cutting - and saw the jumbled mess of iron and steel.

Ladders and ropes were used to help us get down there.

'Quiet determination'

A man's body was pulled from the wreckage, followed by a woman who had suffered multiple injuries.

We removed another body, leaving only one in place: a man thrown from one of the first two carriages on the Poole train.

At 15:52 another radio message was sent: "All bodies now removed from remaining coaches - British Rail heavy cutting and lifting units in operation. Brigade crews now standing by."

I played a very small part in the rescue operation: one of about 250 firefighters who attended the incident.

Faulty wiring and an incorrect signal was found to be the cause of the crash

I could not imagine what the scene was like for the very first crews to arrive confronted by hundreds of injured people. But we worked with quiet determination to make sure that the final bodies were recovered with as much dignity as possible.

It took more than a year for the 250-page report by Anthony Hidden QC to be published.

It found that faulty wiring had caused an incorrect signal to be displayed to the driver of the Poole train, who was driving into a blind bend and had no chance of stopping.

This crash was by far the largest incident I had attended at that point in my firefighting career.

Of course, I had attended other incidents where people had died. But none of them were on this scale - even 25 years ago, it remains difficult to take in.