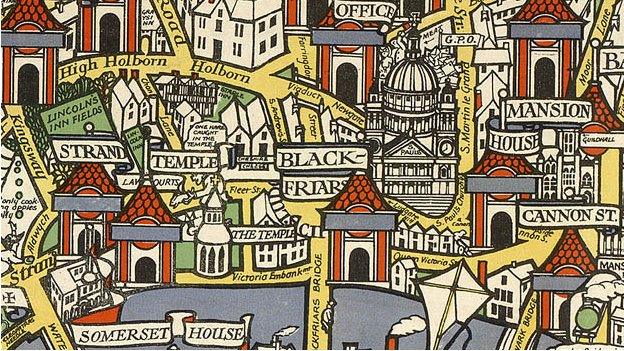

What lies beneath London?

- Published

From deep-level air raid shelters to the colossal Crossrail construction, beneath London lies a labyrinth of tunnels. BBC News delved underground to visit some of the capital's rarely seen subterranean spots.

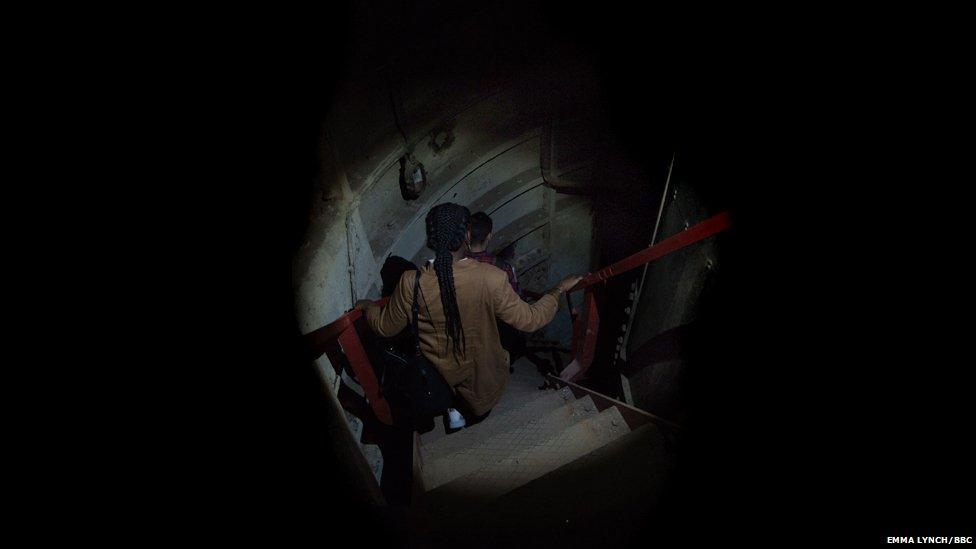

Walking past the gastro pubs and swanky new apartments of south London's rapidly gentrifying Balham Hill, it would be easy not to notice a small black door.

Behind it is a 178-step dusty spiral staircase. It's the only way to get down below. The lift is out of service.

We are led down by a dim mobile phone light until we reach about 30m (100ft) below the Northern Line.

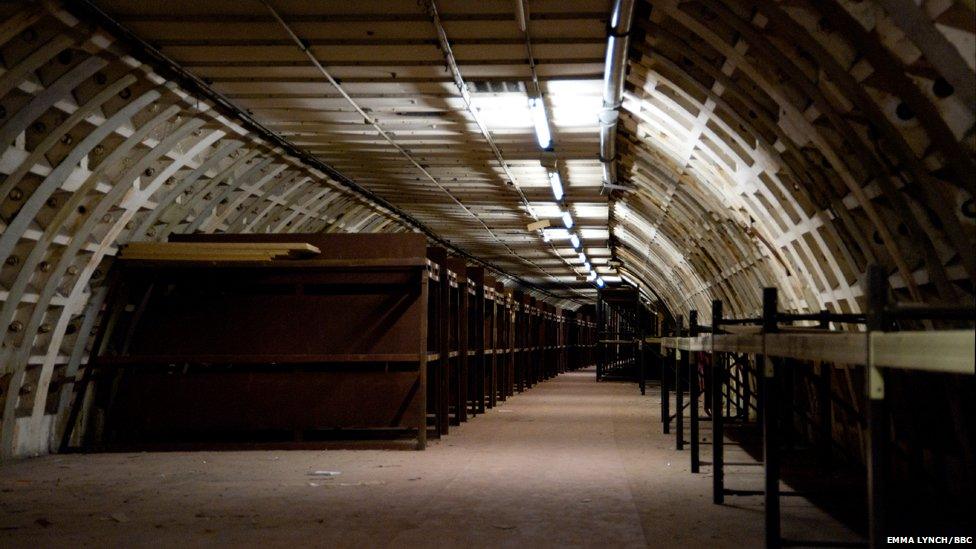

A light is switched on and we find ourselves in a dusty low-ceilinged tunnel. There's a chalky, musty smell and a chill in the air. You can hear the Tube trains rumbling above.

Clapham South's deep-level shelter was originally built as part of a new railway line planned to run between north and south London.

"It was the Crossrail of yesteryear," London Underground (LU) operations director Nigel Holness says. "But our forefathers didn't have the foresight or the funding for the railway to be completed."

We enter another tunnel within the complex where small rigid-springed bunk beds line the walls.

The tunnels were dug by hand during World War Two and were used as an air-raid shelter.

More London subterranean spaces

Ghost Tube stations - There are more than 20 abandoned stations on the London Underground network

London Post Office Railway - 23 miles (37km) of track remains under London with plans afoot to develop them into a tourist attraction

Lost rivers - Dozens of rivers including the Fleet and Walbrook were buried beneath London's streets more than a century ago

Camden catacombs - Beneath Camden lies a network of catacombs used as stables in the 19th century

Pindar - A bunker beneath the Ministry of Defence in Whitehall, where Henry VIII's wine cellar can be found

The shelter could hold up to 8,000 people with facilities including toilets, a nursing point and a canteen, where jam sandwiches were served. But it was never used to its full capacity.

"A big concern of the government was of a troglodyte society forming if people got used to living underground," says LU's Philip Aish. "Cowering in holes in the ground wasn't seen as the British thing to do in the Blitz spirit."

In 1948, when the Empire Windrush arrived in the UK, with more than 400 Jamaican passengers onboard, the tunnels were once again put to use.

The Great Britain they found may not have been quite what they had expected. When they docked at Tilbury, the new arrivals were put on buses, taken to the shelter, and spent up to six months living deep underground until they found other accommodation.

"One of the reasons there is such a large African-Caribbean community near is because the work exchange was in nearby Brixton, so a lot of them ended up there," says Mr Aish.

Now the shelter is up for lease and LU is "open to innovative ideas" on how it could be used, says Mr Holness.

Seven other similar London shelters have been rented out for storage purposes and, in one instance, an underground farm, supported by celebrity chef Michel Roux Jr.

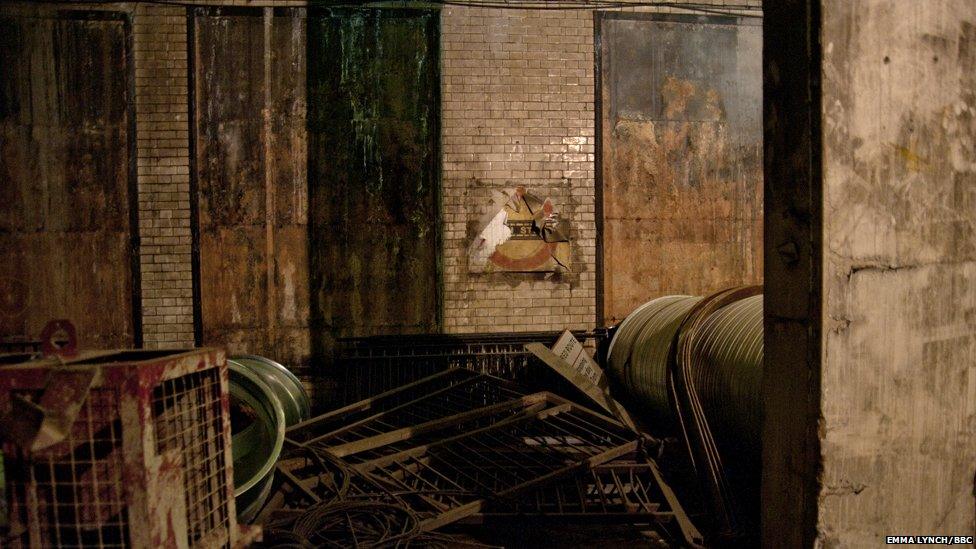

Next on our subterranean trip, we visit a narrow, dimly lit, leaf-clad staircase leading down to an empty platform in central London. It's only about 20 steps below ground, then only one more small step from the platform to the track.

This doesn't sound like where you would expect a tour of Europe's largest construction project - Crossrail - to begin. But the disused Kingsway Tram Tunnel plays a vital role in the scheme.

The tunnel once took passengers from Holborn to Waterloo Bridge. But for the past 60 years it has been mostly neglected, occasionally being used as a film set.

Posters peeling from the tiled walls display mock-up London Underground signs for a fictional Union Street station.

But now the tunnel has proven invaluable to Crossrail. From here engineers pump grout through shafts deep into the ground to allow nearby buildings to be protected from any potential movement from tunnelling.

"London is very busy, day and night, and having these spaces is very important," says site manager Pawel Czajkowsk. "Without them, Crossrail would have been impossible to construct."

With more than 10,000 workers, 40 construction sites and 26 miles (42km) of tunnels being bored beneath London's streets, the numbers reflect the immensity of the project.

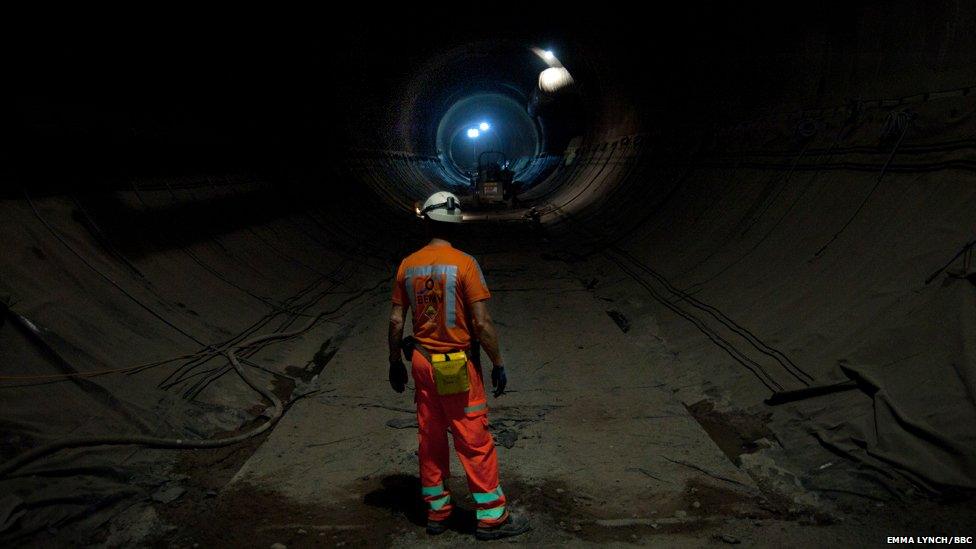

At Finsbury Circus, in the City of London, where the new Liverpool Street station is being built, you get a true feel for the scale.

A temporary 42m (137ft) deep shaft provides access to the tunnelling where 250m (820ft) platforms are being constructed.

From 2018, up to 24 trains an hour will pass through the station, linking the City with Canary Wharf, the West End and Heathrow.

Giant diggers are at work as concrete is mixed on site and a technique called sprayed concrete lining (SCL) is used to seal the tunnel walls.

Site manager John Rodgers describes the complexity of the project thus far, given the amount of subterranean networks already in place.

"There is 2ft between us and the Hammersmith and City Line. We are under the Post Office Railway tunnel. It's 1ft between us and that," he says. "Then there's the second largest sewer in London - the Goswell Sewer. We had to go under that."

But regardless of the number of tunnels that already exist beneath Londoners' feet, urban planners are showing little sign of relenting in their ambitions.

With boring of the 15-mile (25km) Thames Tideway, external "super sewer" tunnel scheduled to begin in 2016 and a Crossrail 2 on the cards, external, the capital's subterranean schemes look set to continue for decades to come.

All photos subject to copyright

Related topics

- Published28 January 2014

- Published10 January 2014

- Published14 April 2012