Leicester Square: Do London's cinemas face a fight for survival?

- Published

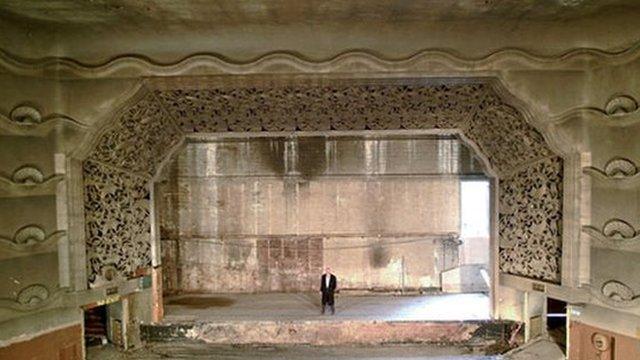

The Empire Leicester Square cinema, prior to its conversion into an IMAX

London's Leicester Square is home to some of the UK's oldest and most beautiful cinemas - but unlike the equally famous West End theatres nearby, none have listed building status. Now, with developers circling, many are worried how long these buildings will last.

The 1930s Odeon West End, one of Leicester Square's oldest picture houses, has already been approved for demolition despite being in a conservation area and opposition from English Heritage.

There is nothing to stop others going the same way. Supporters fear they face a losing struggle to protect the most important cinemas in an area of central London hungry for ambitious new developments.

"Cinemas should be protected - they are a hugely important part of the history of our 20th Century towns and cities," says Henrietta Billings, senior conservation adviser at the Twentieth Century Society.

"Not only do they chart an interesting period of public entertainment - from their heyday as American Hollywood movie palaces, to slow decline in the post war years with competition from television - these enormous buildings were often fantastically elaborate 'Cathedrals of the Movies'."

But why is the design of these buildings so important?

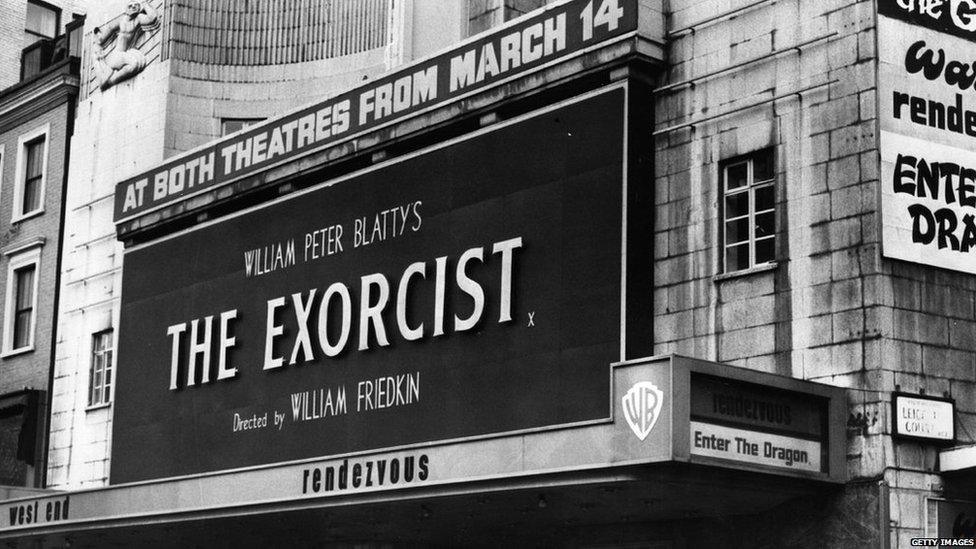

The Warner Theatre, which is now the Vue West End

Turn the clock back 70 years and many of the ambitious new developments were cinemas themselves.

Great cathedrals for the silver screen were rising across the city, some of the most imaginative auditoriums ever seen, bringing the glamour of Hollywood to central London, as well as less glamorous areas of the capital and the rest of the UK.

Gigantic and palatial auditoriums fit for Hollywood royalty themselves boasted the biggest screens ever seen; rows of velvet seats, palm trees and awe inspiring interiors ranged from Egyptian-inspired art deco to gothic-influenced design.

"The cinemas were designed to take people into a kind of fantasy land," explained Richard Gray, chairman of the Cinema Theatre Association, a heritage group. "It was joining with the fantasy of the film that you were about to see.

"I think the idea was to gobsmack the audience, in one way or another. Each cinema outdid the last one with a sensationalist interior."

Leicester Square's cinema history

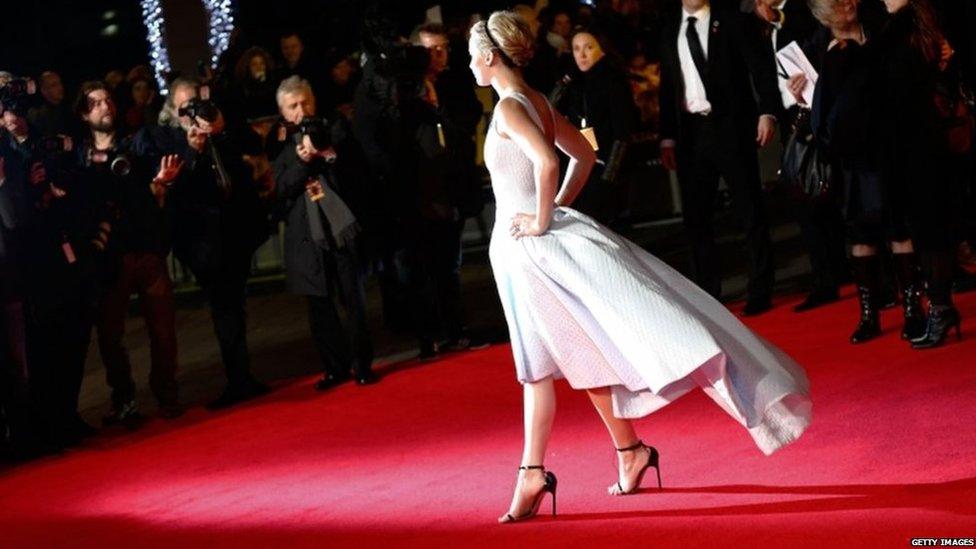

Jennifer Lawrence attends the world premiere of The Hunger Games: Mockingjay Part I at the Odeon Leicester Square in November 2014

In Victorian times Leicester Square was celebrated for its Turkish baths, oyster rooms and above all its theatres. The Survey of London described the square as "essentially masculine" and "no place for unescorted ladies..."

The Empire Theatre was closed and demolished in 1927 and replaced by the Empire Cinema in 1928 offering cine-variety entertainment

In 1937 the Alhambra was replaced by the gigantic Odeon Leicester Square.

Cine-variety, a mixture of films and live shows, fell out of fashion as the century progressed and in 1962 the Empire was redesigned by architect George Coles to become a 1,330 seat cinema

As home to the largest cinemas in London, Leicester Square hosted star-studded premiers throughout the 20th Century

Since the subdivision of the Empire's auditorium in 2013 to create an IMAX, the Odeon is now the largest operating one-screen cinema in London

So why do cinemas seem particularly vulnerable to the demolition ball now?

Unlike their architectural cousins, the West End theatres, many cinemas lost their original features in the race to keep up with technology.

First, in the 1950s, came the demand for massive curving CinemaScope screens. Then dawned the era of the multiplex. Picture houses that once housed one big screen and a thousand seats were carved-up to accommodate three or more small screens.

Such changes were introduced sympathetically in some venues - as in the now Grade II* listed Odeon in Muswell Hill, north London, where most of the original auditoriums' features have been retained.

At other times the alterations were more brutal, leaving little evidence of the cinema's glamorous past.

For instance, the space that in 1967 housed Europe's biggest CinemasScope screen at Odeon Marble Arch is now filled with five smaller screens.

The art deco Troxy Cinema in east London has returned to use as a multi-entertainment venue including film screenings after years as a bingo hall

The Odeon Swiss Cottage retains its art deco exterior but with a radically updated interior, now featuring an IMAX screen

Even one of London's most famous cinemas, the Empire Leicester Square, has succumbed to the most recent demands and installed an IMAX screen.

The cinema, which was for more than 50 years the biggest auditorium on the square, was subdivided to accommodate the new screen. Changes like that make it difficult for a cinema to ever be granted listed status.

Justin Ribbons, chief executive of Empire Cinemas, defended the changes made to the 130-year-old building.

"With each regeneration there is obviously a balance between maintaining the historic building and installing the new technology and imperative film marketing," he said.

"However, I think Empire Leicester Square is one of the best examples in London of sustaining both.

"You can't preserve the old building in its entire original form and purpose without it becoming irrelevant to today's entertainment industry. For us the building is tantamount with the business, and from that point of view we will always cherish and preserve as much of the building as we can."

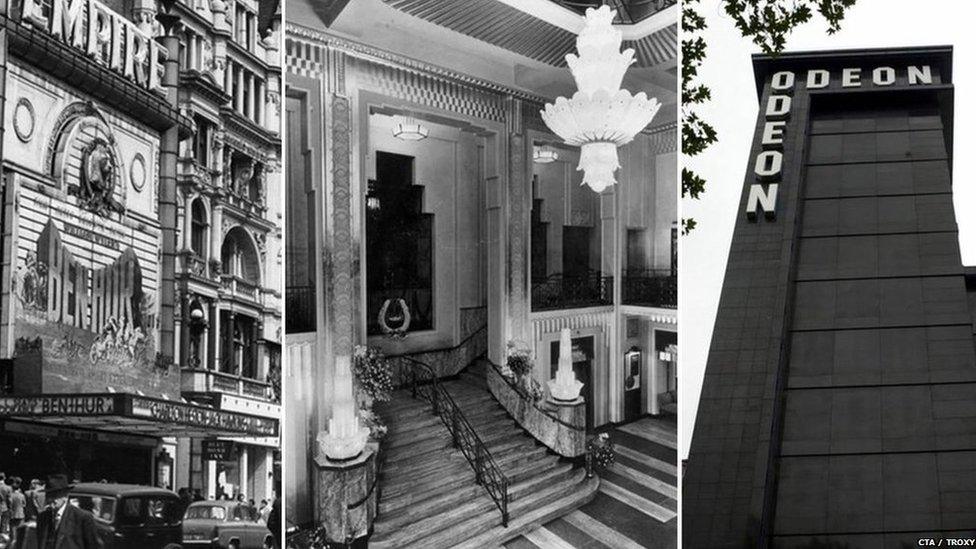

The Empire Cinema, Leicester Square, the lobby of the Troxy, east London, and the tower of the Odeon Leicester Square which still stands today - despite not being listed

English Heritage said it opposed the application to demolish the Odeon West End but explained that both the Empire and Odeon Leicester Square had been too significantly altered to be listed.

"The concentration of both cinemas and theatres in the West End is something we naturally take into account, but we nevertheless have to judge each building on its own merits," a spokesman said.

But despite the building's failure to meet English Heritage's standards, the Odeon Leicester Square (not to be confused with the Odeon West End, also in Leicester Square) is the biggest single screen cinema left in the UK, and remains a favourite among cinema aficionados.

With its famous black marble tower, it remains a valuable piece of the city's heritage and one of the most impressive places to see a film in London, according to Mr Gray.

"It has been emasculated and emaciated, compared to what it was... it did have this world class interior which was smashed to bits in the 1960s, but you still feel as though you are somewhere quite special," he said.

Cinemas at risk

Wallaw Cinema, Blyth

Astoria, Brighton

Whiteladies, Bristol

Odeon, Chester

New Victoria/Odeon, Edinburgh

Lyceum, Glasgow

Picture House, Govanhill

State Cinema, Grays

Carlton, Islington

Regal, Kingston-upon-Thames

Source: Cinema Theatre Association

Duncan Reynolds, the managing director of Odeon UK, points to the recent refurbishment of the Odeon in Swiss Cottage, north London, as evidence of a commitment to preserving the best of the past.

While the bulldozers may seem to be circling in the heart of London, elsewhere in the country there are a growing number of successful restoration projects.

The Rex in Berkhamstead and the Odyssey in St Albans, both in Hertfordshire, and the Regal in Evesham, Worcestershire, were all saved from the shadow of the developer's digger to become thriving cinemas in fully restored art deco glory.

In Stepney, east-London, the gigantic Troxy - a 1933 cinema and once a Mecca bingo hall - is now open again as an entertainment venue with occasional film presentations.

Daniel Smith, business development manager at the Troxy, explained the enduring appeal of this elegant old cinema.

"The 1930s was a very glamorous era where the environment that people were going to enjoy entertainment was just as important as the activity, and Troxy is a prime example of this," he said.

"Fragrances used to be pumped into the venue through the ceiling ducts to keep the space smelling fresh and the stunning original 1930s art deco architecture speaks for itself."

So while cinemas in Leicester Square may face an uncertain future, with a bit of imagination others have proved there's still life in the old picture palaces yet.

- Published2 December 2014

- Published21 July 2014

- Published14 June 2013