London Mayor Election 2016: What is a Londoner?

- Published

Two candidates for mayor have promised housing for "Londoners first". But how do you define a Londoner?

Every political campaign has its buzzwords, the phrases that dominate. For the London mayoral campaign, it seems, one of those is "Londoners first".

Zac Goldsmith, the Conservative contender, wants to "give Londoners the first chance to buy new homes built in London". He says this would mean having lived or worked in London for at least three years.

Labour's hopeful, Sadiq Khan, has pledged to "deliver more affordable homes, and 'first dibs' on those homes for Londoners". He says that means anyone currently living or working in the city.

UKIP's Peter Whittle, keen to point out he is a "Londoner born and bred", has said he does not want to see Londoners leave the city.

But what exactly is a Londoner, if such a tribe exists? How should we understand their needs, thoughts and feelings?

Place of birth

Tara went to the same south London school as her mother before her, while Susannah has swapped London for Edinburgh

Staking a stronger claim than most under this category is Tara van Gastel, 30.

She was born at St George's Hospital, Tooting, and went to the same Tooting school as her mother before her, who moved to south London from Jamaica as a child. She says her parents, despite emigrating in the 1960s, see themselves as Jamaicans first, whereas she and her siblings are very much Londoners.

She takes a firm line: "It totally annoys me when tourists come from the shires and claim to be from London. Unless you were born here, and raised here, and have seen the changes in London from the 1980s at least, then no, you're not a Londoner."

She says for her, being a Londoner is bound up in the memories evoked by different parts of the city: "For me, walking down The Cut in Waterloo will always be exciting. Getting off the bus there and feeling like you're in old London, looking at the [Old Vic and Young Vic] theatres, it definitely gave me the idea of becoming a drama teacher."

Susannah Howie, 30, was also born and raised in south London but takes another view. She moved to Edinburgh to study nine years ago and never left.

"When I go back to London to see my family I feel like a bit of an outsider - things in London change so quickly, when you're thinking 'oh, you can pay for the Tube with your debit card?' you feel like you're not in the know any more".

But there are upsides to this, she says. "In Edinburgh I've been able to save and buy a flat - that would never happen in London."

Where you live

Jenny Imhoff, left, calls London home, but Rob Madigan sees himself as a true blue Scouser

Can "London-ness" be thrust upon you? Not according to Rob Madigan, 47, who has lived in London for 28 years since leaving Merseyside, but still defines himself as a Scouser.

As well as being a pub landlord, he's a member of Everton (London Area) and the social secretary for the Association of Provincial Football Club Supporters in London.

In order to join, you can be a supporter of any non-London club. It says its members share a "common bond of dislocation".

While its main mission is to facilitate travel to matches, it also runs its own darts, pool and football leagues. Mr Madigan says it is somewhere where "we can all feel at home" and while he still pledges allegiance to Liverpool, he says: "I wouldn't want to go back now - I've got a job and a family, the opportunities are different here."

Jenny Imhoff, 30, is from north-west Germany and moved to London in 2007, initially to study. She stayed for work - currently she is employed by a tech consultancy - and lives in Tottenham.

She says: "I'm very comfortable calling myself a Londoner. If I go away the idea of 'returning' always means returning to London, for me.

"The town has become my base I guess."

She sees it as a friendly city where there's lots going on, but the down side is that it's "really expensive - especially as a young person you know you're opting for a lower quality of life to what you might have elsewhere in Britain or Europe".

Despite that, the idea of a "Londoners first" policy worries her. "I don't want exclusionary policies coming in via the backdoor. I'd really just prefer there to be discussion about fixing the housing market in the interest of people who need somewhere decent to live."

Familiarity

Gert Kretov, originally from Russia, now runs his own academy teaching cab drivers The Knowledge

If there is one thing most native Londoners pride themselves on, it is their skill as geographers.

"Not that way!" they'll scream at you as you make an innocent left turn, if they're not busy swearing you to secrecy over the quickest way to get out of King's Cross station.

None more so perhaps than black-cab drivers, who have to pass the Knowledge, an exam that requires drivers to learn 25,000 street names.

Among its graduates is Gert Kretov, 39, who moved from Moscow to London in 1991. After initially finding work as a chauffeur he decided to become a taxi driver.

It took him three years to pass the test. Not content to stop there he took over the Eleanor Cross Academy in 2014 and now teaches others how to navigate its squares and alleyways.

Asked if he feels like a Londoner, he says: "One hundred per cent. I understand London. If you dropped me in Moscow now I'd be lost."

He feels positive about the proposals to give so-called Londoners first refusal on housing. He recently moved from north-west London to Ruislip in Middlesex and says he feels like he's being "pushed out" by high house prices.

Attitude

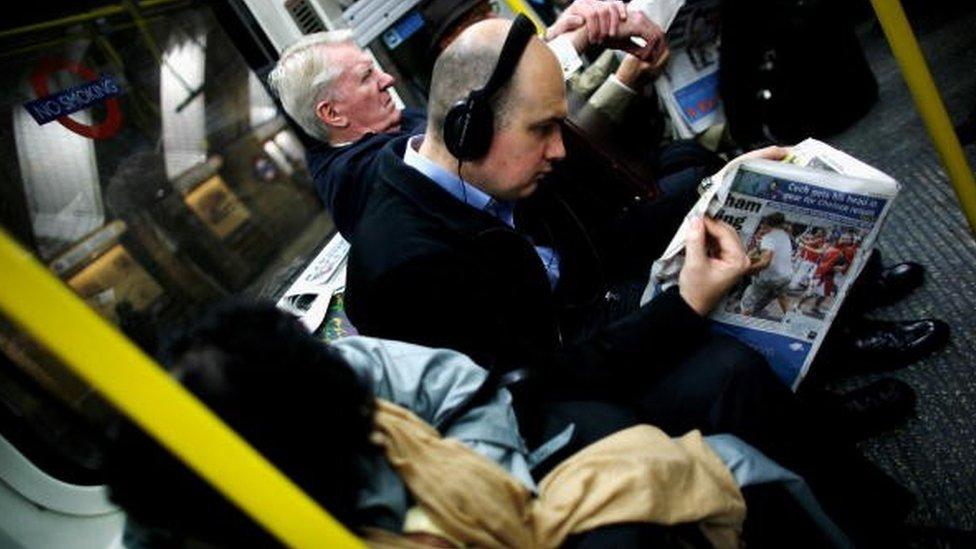

Londoners would no more speak to a stranger in the street than fly to the moon, according to the Lonely Planet

Is London, like New York, a state of mind? Both cities have a reputation for rudeness and indifference.

Dr John Davis, a historian of post-war London at Oxford University, draws attention to this from Hunter Davies' 1966 book The New London Spy:

"The Londoner will listen to the foreigner's query patiently, will speak to him slowly - and also loudly, as though a language of which you don't know one single word became intelligible if spoken loudly enough. When at last the visitor understands him, the Londoner, before the visitor has had time to thank him, will walk on with a shy, kindly smile."

These days, the Lonely Planet guide advises visitors Londoners would "no more speak to a stranger in the street than fly to the moon".

The current editor, James Smart, says Londoners also have a certain "confidence or swagger that goes with living in one of the best cities in the world - but what goes with that is they love to grumble: about transport, about prices". He believes you "see a different side in the local neighbourhood, where people are a bit more likely to stop and chat".

When the city contains those who wear the badge with pride and those who would rather run a mile in the opposite direction, appealing to the "Londoner" vote may turn out to be a fine balancing act for the mayoral candidates in the run-up to May.