What is it like selling sex in London?

- Published

Former sex worker Jenny says she fights for women selling sex on the streets. "They are me, but they are still in it."

Ending the criminalisation of soliciting for sex in England and Wales could lead to one of the most tectonic shifts in how prostitution is seen in society since it was first made illegal nearly 200 years ago. But what is it like to sell your body for sex in London?

On Friday a cross-party group of senior MPs called for soliciting by sex workers to be decriminalised in what would be radical changes to the laws on prostitution.

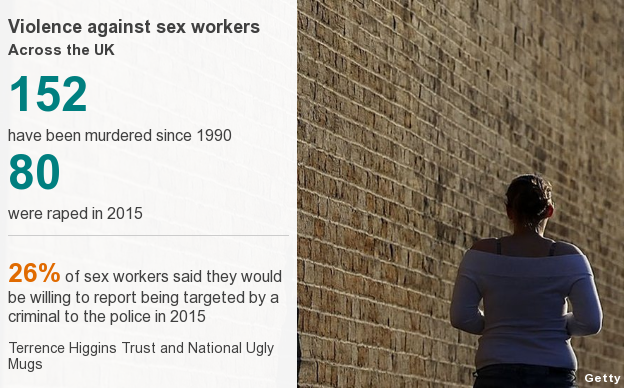

This will most likely be welcome news to London's estimated 32,000 sex workers, external who, charities say, are less safe as a result of the criminalisation of their trade.

Jenny Medcalf says she started selling sex in 2004 when an ex-boyfriend suggested it.

At the time she was working as an actuary, struggling to keep up with the childcare costs for her three children and mortgage payments on her house in Surbiton.

The Durham University graduate says after a difficult marriage and a string of "not so great" boyfriends, she wound up with a different boyfriend who got her into BDSM - an abbreviation for bondage, discipline, domination, submission, sadism and masochism.

"I desperately needed the money, " says Jenny, 47. "I thought I was making a controlled decision to go into sex work to meet my financial needs and I could run it like a business."

Her ex initially organised the bookings and was present for her first punter, she says.

Sex tends to be sold in Soho and Paddington, both on the street and by appointment in brothels

The graduate says she advertised online and would visit men in hotels or their houses.

"I wasn't the traditional type of escort you would see. I was really thin with cropped hair, completely flat-chested and quite boyish but I was offering a BDSM service."

A recovering alcoholic, Jenny says she used drugs to disassociate herself from the emotional and physical toll the job took on her.

After five years working in the industry, there was one moment when she knew she wanted out.

"This guy had me in a cage and he was trying to whip me through it. I swore at him, shouting. I never saw him again, although he wanted to see me. It was a turning point.

"The job had completely broken me."

Staff at Spires often visit the women in prison, or hospital

She says the idea she was in control had "gone completely" and at that stage, she hated herself.

Like women on the street, she says she was going to a client and then on to her dealer - but rather than a £10 rock of crack she was buying £300 worth of speed after a two-hour booking.

The situation became untenable when, unable to face opening her post, she slipped behind on mortgage payments and lost her house - along with her three children, her cats and all of her possessions.

After attempting to kill herself, using drugs and turning to drink again, Jenny met the man who went on to become her husband, whose patience she says helped to give her the strength to transform.

Women working to sell sex on the street are in danger of being taken out of sight and attacked, Jenny says

One morning during her recovery, she woke up and a "light bulb" went off in her head that she wanted to work with sex workers with addictions.

She started volunteering at the Spires charity in Tooting, external and is now one of the charity's most prominent workers. She goes out on to the street at night to find and help people - largely women - who are working as prostitutes.

On the street, these women get around £20 for full sex - but the price can also be as low as £5.

She offers them warm clothing, sweets, crisps, condoms - and support. Jenny and her colleagues visit the sex workers, sometimes in hospital, or prison, often in the middle of the night.

"I fight for the women," she says. "A number are the same age as me. They are me, but they are still in it.

"I respect them as women, I love them as women and I can see they can be so much more than they are at the moment," she says.

Street sex work

Out of the core 200 women known to the charity, seven exited the profession in 2013 and 10 in 2015.

However, selling sex can also be a positive thing, according to one Londoner in her 30s who works privately in a centrally-located flat.

Alice (not her real name), previously a project manager for a large government organisation, started selling sex seven years ago.

Many sex workers on the street have lost their children, often as a result of drug addiction and chaotic lifestyles

A friend introduced her to an escorting website when she was "short on cash", she says.

She sells sex to men, women and couples, along with elderly and disabled people. Intimacy and "skin on skin" contact is a "natural, biological way to make us feel good", she says.

After having had a middle-class upbringing, she says when she first started the work was a "revelation".

"I couldn't believe I was being paid to enjoy my favourite pastime," she says.

Women selling sex on the street are more likely to be dressed in warm clothing and wearing flat shoes than the glamorised idea perpetuated by the media

Her friends, most of her family and her partner, who she describes as the love of her life, know about her work and "completely accept it", although they were worried about her safety at first.

She says she has never been subject to violence but has occasionally been harassed by clients who became overly emotionally attached.

While the stigma of the work can make it difficult, she says, her clients are "nice, ordinary people".

"I do not need rescuing," she adds.

Alice's and Jenny's stories are played out on a larger scale across the country.

A 2015 survey by the NUM foundation and Leeds University found, external 71% of the sex workers who took part had previously worked in health, social care, education, childcare or the charity sector.

Alex Feis-Bryce, director of services at the NUM foundation, says that rise has, in part, been caused by cuts in recent years to public sector jobs and charities.

People are attracted to the flexibility of the work, he says.

Spires said it had seen a steep increase in the number of male sex workers in south London

Forty-five per cent of the 240 contributors to the survey, which ran between November 2014 and January 2015, sold sex alongside holding down another job.

"Something we are seeing more and more of is private escorts being stalked and harassed - we saw a 188% increase in the numbers of cases between 2014 and 2015," he adds.

Alex says these workers are often blackmailed by people taking advantage of their situation and the need to remain anonymous - threatening to tell partners or employers.

Shrinking funding for services helping sex workers meant the situation was pretty "grim", he adds.

Of course, sex is still sold on the streets of the capital. However, the idea perpetuated by Julia Roberts' character in the 1990 blockbuster Pretty Women, of risqué dressing and glamour, is not generally reflected by so-called streetwalkers in London.

Women selling sex on the street are more likely to look like a friend, an aunt or a mother - they tend to be wrapped up warm, as standing on a street all night is cold - and wearing comfortable shoes, not the killer heels often seen in the media.

Met commander Christine Jones says she wants to stop exploitative individuals making money in the "most appalling ways"

They are not likely to be heavily made-up.

Met Police commander Christine Jones says she often finds women working within the sex trade are there as a result of coercion, a lack of choices, and vulnerability.

She says she tries to put the care of women at the "heart of everything", as it is the punters who create the demand and bring violence and anti-social behaviour to communities.

She says targeting people who exploit women and buy sex is "at the top" of the Met's agenda - rather than taking the women into custody. "I think that is a really important message to get across," she adds.

Criminalising punters puts sex workers' safety at risk, says Laura Watson at the English Collective of Prostitutes

But the story on the ground is perhaps not so cut and dried, according to Laura Watson, a spokesperson for the English Collective of Prostitutes.

Laura says she hasn't seen police moving away from targeting sex workers.

"We are fighting cases where women are being hounded by police officers," she says.

She says the women she works with "do not trust" the police to look after them once they report a violent crime. Some have been threatened with arrest when they do so, Laura adds.

And in reality, targeting the punter rather than the worker has a similar "detrimental impact" to sex workers' safety as they are forced underground, she says.

Women get around £20 on the street for full sex

Laura adds: "Women are more likely to go into different areas they don't know just to pick up clients, or their negotiating time could drop as the client is worrying about being caught so all of the safety measures are diminished.

"Terrible things happen as a consequence of that."

She says most of the women are mothers and so can't afford to stop working.

And the number of people turning to prostitution has increased since the recession, due to benefit sanctions and job cuts, she says. This means women who were once sex workers are returning to the profession.

Another facet of criminalisation means women struggle to find other work, Laura adds, so it is harder to leave should they choose.

Whether or not the MPs' recommendations make it into legislation remains to be seen - and any such move would almost certainly be reserved for a calmer period in UK politics.

Although some, like Alice, are able to make prostitution work to their advantage, many struggle with the reality of making a living out of something so intimate.

- Published21 October 2014

- Published12 April 2016

- Published4 March 2016