What is Boris Johnson's legacy for London?

- Published

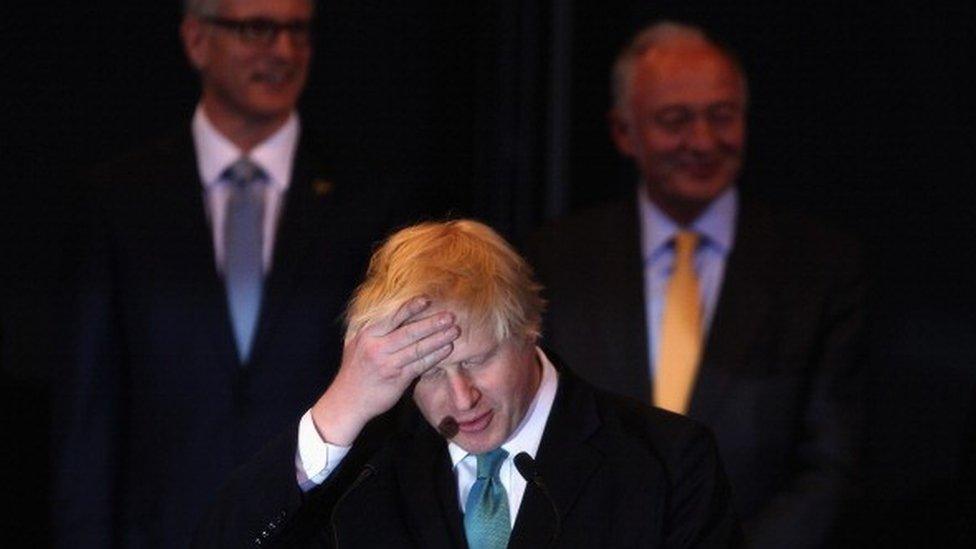

Boris Johnson's eight years as London Mayor comes to an end this week when his successor will be elected. But what legacy does he leave for the capital?

Cast your mind back to the summer of 2007, when the Conservatives were a party in search of a mayoral candidate. When Boris Johnson's name was first mooted, it was met with incredulity and mockery from many quarters - and blank denial from officials.

But even critics who dismissed him as a clown could see instantly the possibilities for all the wit, charm and intellectualism. And Ken Livingstone realised instantly that the Henley MP could well prove to be his nemesis.

Boris Johnson's allies say he helped London come through the economic crash and surfed an Olympic wave to make the capital feel good about itself again.

The London mayoralty was not just the making of Boris Johnson, more his salvation.

It allowed him a second chance to build a credible political career after his first foundered on reports about his personal life, tabloid ridicule and parliamentary mediocrity.

The speeches now marking his farewell from City Hall have underlined the positive trends to come out of it. He has pointed to falling crime, rising employment, an efficient transport system, greater life expectancy even, as evidence of his inspirational leadership and steadiness at the helm.

But did he repay the voters' faith and make enough use of the powers and levers at his disposal?

He certainly defied - in fact capitalised on - low expectations and serious underestimation. In itself it showed a kind of genius. The comic dishevelment engaged; the harrumphing humour disarmed. And nothing blunted the ambition and political calculation.

He owes London big, having arrived at City Hall in 2008 with a scant knowledge of and little past documented interest in the affairs of the capital. He leaves having amassed a broad experience of how to run things - furnished, effectively, with a crash course in governance.

But if his personal popularity appears to have been buoyed by - or survived, depending on your point of view - two terms in office, does he also now demand to be considered credible as an administrator, as someone who made a difference?

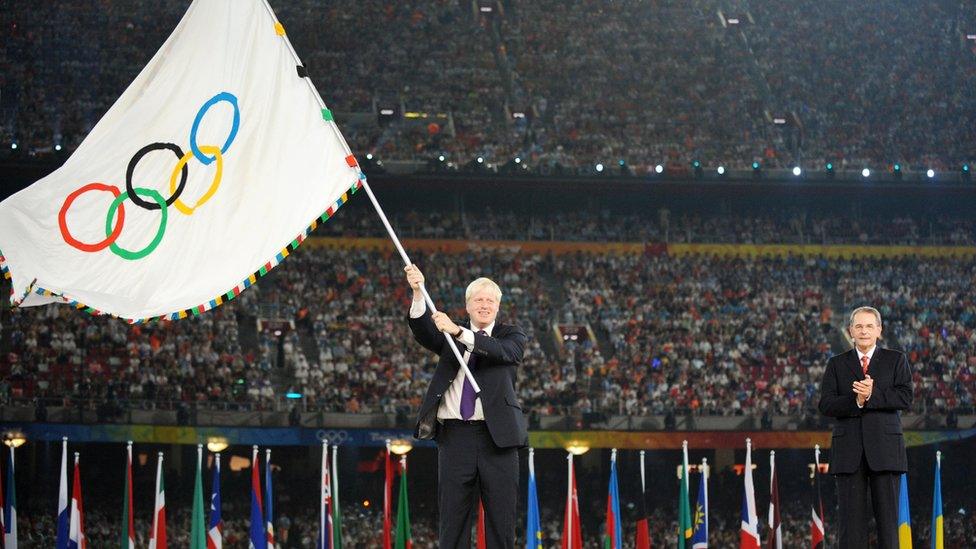

Mr Johnson exploited brilliantly the occasion of London 2012, long in the planning. To a large extent his first mayoral term was preoccupied with the Games, and ensuring he was still in place to enjoy the spoils by winning his second term in office just three months before the global sporting event took place in his city.

But many critical observers feel that after that glorious month, the second half of his mayoralty was low both on substance and strategy - not disguised by the occasional "grand vision" for the capital in 2020 or 2050 or beyond.

Boris Johnson shouted "gold medal" while dangling on a zip wire for several minutes. Video: Laura Mullane

He can rightly claim to have helped set east London on the way to an Olympic infrastructure legacy. Homes are being built (although many at prices unheard of in the area a few years ago), and there's an academic, cultural and sporting hub taking shape (even if West Ham United Football Club got a supreme deal to move into the iconic stadium).

But the transformed life chances promised for the local population did not materialise from the legacy programmes to help the long-term jobless.

Elsewhere, he derived much political capital from the progress of Crossrail, but other major infrastructure projects were hard to come by. Small pots of cash appeared now and then from a chancellor with whom he had a less than warm relationship, for feasibility studies into river crossings and other transport links.

In the main, critics argue, this has been about reinstating the ideas of Ken Livingstone that could have got off the ground years ago, and that it characterises Mr Johnson's time more as hiatus than progress.

Mr Johnson paints a brighter picture of his regeneration in "opportunity areas" where new communities are taking shape.

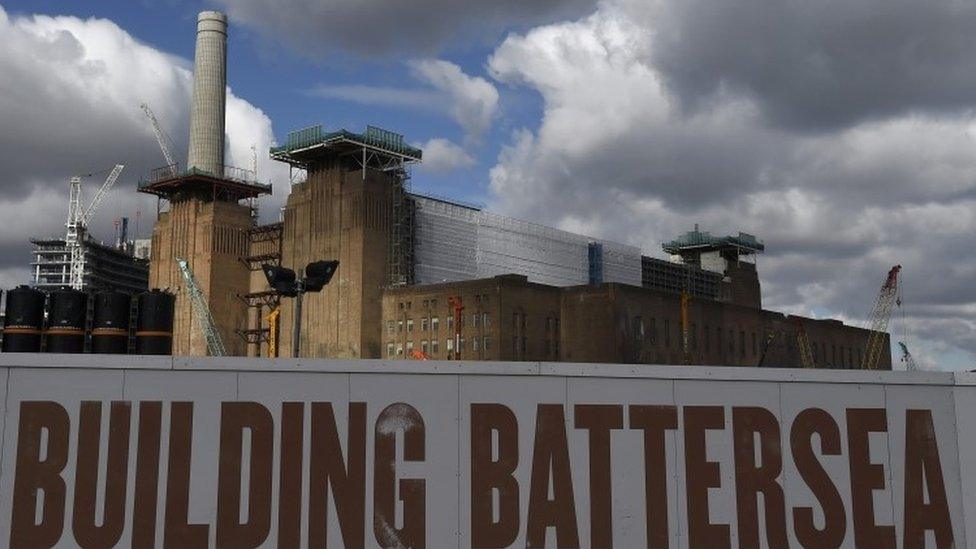

He often points at Battersea's crumbling old power station, where the Northern Line is being extended, two new stations built and a cluster of very tall buildings emerging around the US embassy and a Chinese-backed luxury hotel. Little taxpayers' money has been necessary.

But this too tells its own story: vast amounts of Malaysian money, lots of off-plan foreign buying but virtually no affordable housing. Plans for homes for more than 20,000 people, but not one new state secondary school. And the only health facility happening so far? A private clinic. Not the kind of community some hoped would be created.

Overall on housing, Mr Johnson can claim that numerically he built more affordable homes than Mr Livingstone. But "affordability" is now more loosely defined.

And once the money injected by Gordon Brown's government ran out, the trajectory was downwards: 55,000 affordable homes in Johnson's first term; 45,000 in his second.

He talks of looking out of his City Hall window at the cranes and diggers he says signify a revival, a building boom even. But he's been in charge at a time of arguably London's worst housing crisis. Did he do what he could?

Although the capital's population is rising by 100,000 each year - and for all the flexible non-prescriptive approach, warm encouragement to developers and removal of barriers to build - only 5,000 affordable new homes were completed last year as Mr Johnson prepared to leave the scene.

There have been operational transport trends to celebrate. Punctuality and performance on the Tube improved, and the London Overground rail network has flourished.

However, relations with the unions remained strained, and no trust was established. It has led to the introduction of a weekend all-night Tube service being delayed.

Mr Johnson will certainly be remembered for a fondness for monuments: visual statements like the Thames cable car (completed), the Garden Bridge (a work in progress) and the ArcelorMittal Orbit sculpture (currently being modified to include a slide).

What has remained undimmed is his sense of place and liveability.

He has planted trees and encouraged urban horticulture, and tried to keep alive the Olympic volunteering spirit. But he embraced skyscrapers too warmly for many and his vision of "space-sharing" - where motorists, cyclists and pedestrians co-existed in a kind of highway harmony - soon fell by the wayside, with traffic congestion now right back up there as a major gripe and a big problem left for his successor to sort out.

He will always be associated with bikes, and more people are now cycling in London than ever before. Yet the "cycling revolution" has come along a perilous pot-holed path.

A sponsorship deal with Barclays for the hire scheme wasn't good enough for him to fulfil the promise to make it self-financing, and the first iteration of a new network of cycle routes had to be re-thought after death and injury.

He faced uncomfortable months, when he was accused of failing to match a tally-ho enthusiasm on cycling with safe public policy. Yet today segregated cycle lanes are being introduced, which it is hoped could lead to a step-change in habits and give the outgoing mayor a genuine two-wheeled legacy.

Just as awkward for a time was the test of leadership that was his response to the phone-hacking scandal. He dismissed it originally as "codswallop", and was accused of not using his office to push the Metropolitan police to do more sooner - something he denied at the time.

Helped by his own considerable success as a journalist, he's been assiduous in keeping friends in the right places. His highly remunerative column, external still engages readers of the Telegraph and he holidays at the Tuscan villa of the owner of the Independent and Evening Standard. All good positioning for the leadership manoeuvres ahead.

But did he deploy his London mandate to the full?

On top of the direct powers and budget responsibilities of the office comes the vast scope to influence. And with Mr Johnson, themes came and went.

For a while it looked as if the life chances of young people would become a major focus. He pledged to sponsor at least 10 academies, partnered with business. Just four materialised, one was deemed by Ofsted to be struggling, and the programme was discontinued.

There was energy devoted to gangs and rehabilitating young offenders. But the mayor made exaggerated claims about the success of a flagship youth offending scheme, and with "payment by results" hampering the project, this too fell off the mayoral agenda. Meanwhile, violent crime is starting to rise again.

It could be argued that austerity and difficult finances made the synergy between Conservative mayor and a Conservative-led government less fruitful for the capital than many expected - hindered perhaps by rivalries and resentments.

On various occasions Mr Johnson irked the prime minister, though David Cameron never betrayed it publicly.

The mayor blamed police cuts at the time of the 2011 summer riots, talked unhelpfully about welfare changes in terms of "Kosovo-style" ethnic cleansing, and objected loudly when a Cabinet reshuffle appeared to signal a shift towards further expansion at Heathrow.

His relationship with the Home Secretary Theresa May - never warm - found a new chill when she refused to approve the use of his (already paid for) second-hand German water cannon.

As they began to emerge as Mr Cameron's two most likely successors, Messrs Johnson and Osborne jousted behind the scenes over what London needed and what it would be given.

At City Hall, the mayor left much of the detail and heavy-lifting to a cadre of deputies and advisers. The verdict of many who have watched him most closely is that he has often been pragmatic, rarely letting the best be the enemy of the good.

But a big question raised is over the limited nature of what he set out to achieve and the perceived lack of ambition. Perhaps with the thoughts on the future, venturing little provided less chance of failing.

In the story of London's progress under an elected mayoralty, will his time come to be seen mainly as an entertaining intermission?

Find out more about who's standing in the London elections., external

- Published21 February 2016

- Published6 August 2014

- Published1 August 2012