Five ways the Great Fire changed London

- Published

Oil painting of the Great Fire seen from Ludgate, c1670. Originally black with dirt, the painting was restored in about 1910, revealing this vivid Great Fire scene

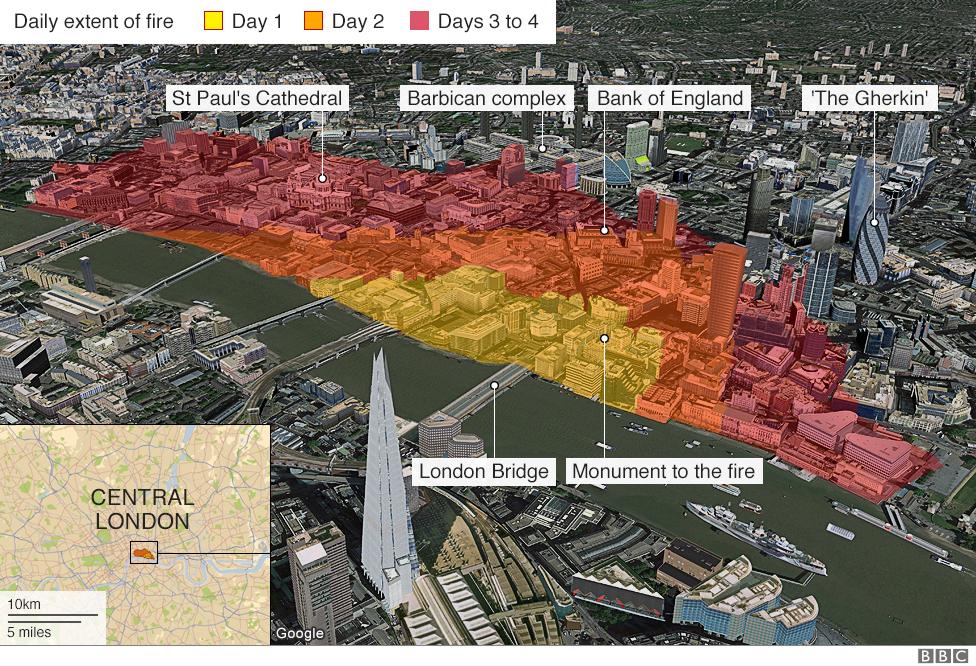

The Great Fire of London raged for four days in 1666, destroying much of the city and leaving some 100,000 people homeless. As the Museum of London prepares to mark the 350th anniversary of the inferno, BBC News looks at how it left a lasting impact on the capital.

A city of stone

The fire raged for five days, making 100,000 people homeless

When a fire began in Thomas Farriner's bakery in London's Pudding Lane in the early hours of 2 September, no-one could have foreseen the damage it would cause.

In a city where open flames were used for heat and light, fires were common. In fact, when Lord Mayor Sir Thomas Bloodworth saw the flames, he was so unconcerned he went back to bed.

But the fire spread quickly - a combination of a strong wind, closely built properties and a warm summer which had dried out the wood and thatch used to construct homes meaning an area mile and a half wide along the River Thames was almost completely destroyed.

But with that came the chance to rebuild the city.

A royal proclamation put a stop to construction until new regulations had been ushered in.

The 1667 Rebuilding Act aimed to eradicate risks which had helped the fire take hold, including restrictions on upper floors of houses no longer being permitted to jut out over the floor below.

The buildings in Pudding Lane 'jettied' out into the street, much like Shambles in York

A flat sign for a London tavern after hanging signs were banned

Importantly, building materials also changed. The 1667 act stated: "No man whatsoever shall presume to erect any house or building, whether great or small, but of brick or stone."

Anyone found to be flouting the new rules would be punished by having their house pulled down.

Not only were houses made of wood in 1666, but so were water pipes, and much of the water supply infrastructure was destroyed.

There were no access points to get to the water without stopping the flow, and in the panic to try and extinguish the fire the pipes were broken and the water drained away.

Steps were taken to rectify this and make the water easier to access - essentially the beginnings of a fire hydrant system.

The Fire Prevention Regulations, printed by the City of London in 1668 stated: "That plugs be put into the pipes in the most convenient places or every street, whereof all inhabitants may take notice, that breaking of the pipes in disorderly manner maybe avoided."

A new St Paul's

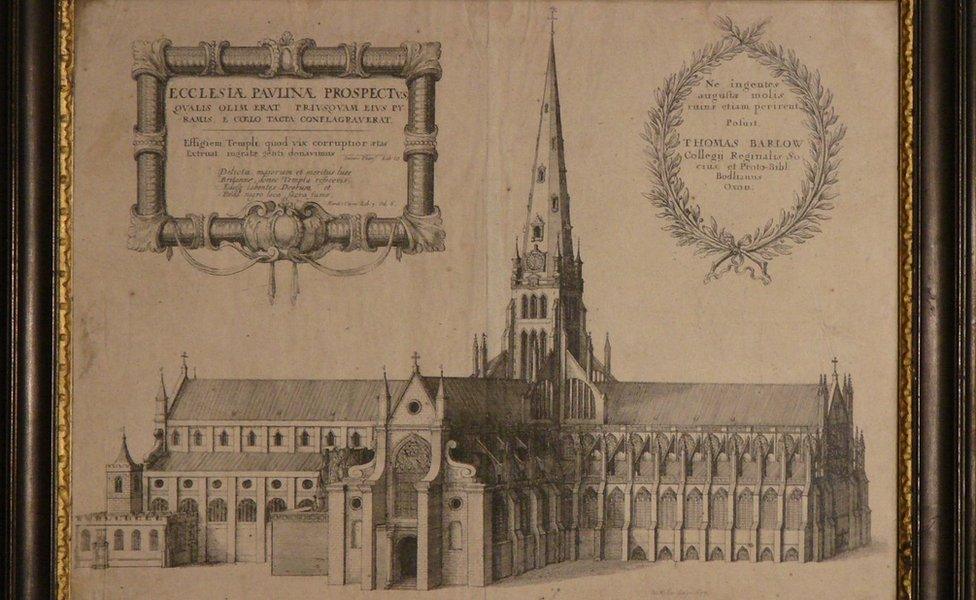

St Paul's is now one of London's most iconic buildings, but in 1666 it looked very different.

The medieval cathedral, which was more than 500 years old when the fire broke out, had suffered years of neglect and was even used by Oliver Cromwell as a stable for his horses.

An engraving of the old St Paul's Cathedral, built in 1087

A reconstruction of the north churchyard at St Paul's cathedral before the fire

Architect Sir Christopher Wren was involved with improvements to the pre-fire cathedral and had submitted designs just weeks before the fire, including cladding it in Portland stone and putting a dome on top of the existing tower.

The age of the building and attempts to support it contributed significantly to its destruction.

When cinders, carried by the wind, set the roof alight, the wooden scaffolding around the cathedral increased the intensity of the blaze.

Not only that, but Londoners' hoped that the cathedral churchyard would be safe and inadvertently made the damage even worse.

"There are reports that local people brought their furniture to the churchyard as they thought it would be safe and stacked it high against the cathedral walls," said Simon Carter, head of collections at St Paul's Cathedral.

"The Worshipful Company of Stationers loaded the crypt with books and paper, and sealed it to keep them safe. But it is likely that when the roof collapsed it smashed through to the crypt beneath, and the books then burnt with exceptional ferocity."

"The heat must have been intense because we have some medieval stones in the cathedral collections which have changed colour as a result of the fire, a witness described some of them as exploding like grenades."

At the time, diarist John Evelyn wrote of "the lead melting down the streets in a stream and the very pavements of them glowing with a fiery redness".

A stone from the medieval cathedral which survived, but the heat of the fire made it change colour

The devastation meant Wren was able to completely redesign the building - but he did not have much concern for preserving any salvageable remains.

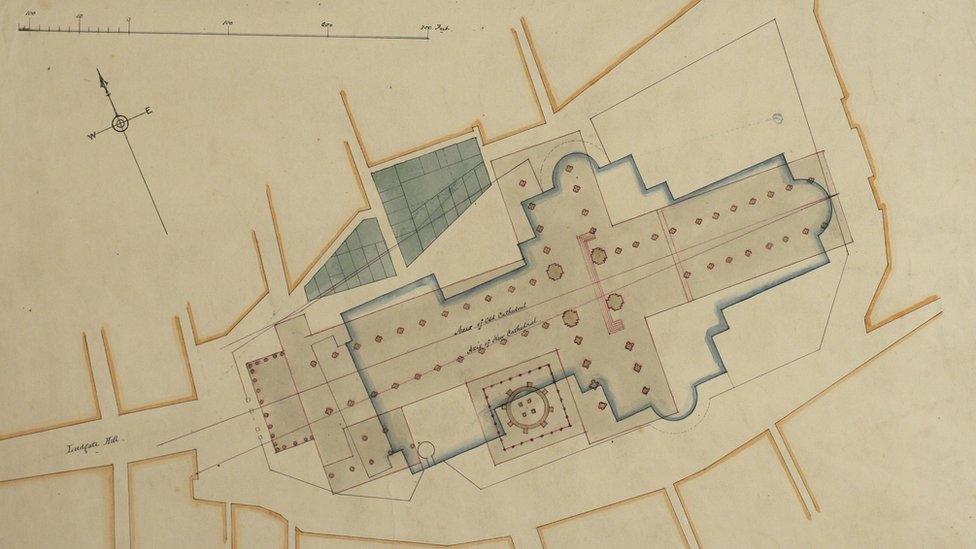

Despite his love of symmetry and mathematics, Wren skewed the alignment of the cathedral from east to west to avoid the old foundations, which he did not trust.

It was also the first cathedral built in a Protestant England and Wren's design reflected the change from Catholicism.

The footprint of the new St Paul's Cathedral laid over the old, showing how the positioning had been skewed

It is unlikely the medieval church would have stood for much longer, but the fire enabled Wren to realise the full extent of his vision for a new cathedral for London.

Wren's gravestone in its grounds bears a Latin inscription which translates as: "If you seek his memorial, look about you."

Other notable buildings

Wren built the Monument to the Great Fire of London. Its height marks its distance from the site of the bakery where the fire began

Five plans were submitted to rebuild the City of London, including one from Wren, who envisaged wide streets branching out from a huge memorial to the fire.

However his vision could not be fulfilled due to a lack of money - landowners still owned the plots where their houses once stood and would have to be paid if a drastic redesign went ahead.

The new King Street was built by carving through private land, which opened up access to the Guildhall - one of the few surviving buildings.

The street layout mostly remained the same, and within 10 years the area ravaged by fire had been rebuilt, bringing new architecture to the old city quickly and on a large scale.

In all, Wren oversaw the rebuilding of 52 churches, 36 company halls, and the memorial to the great fire, Monument.

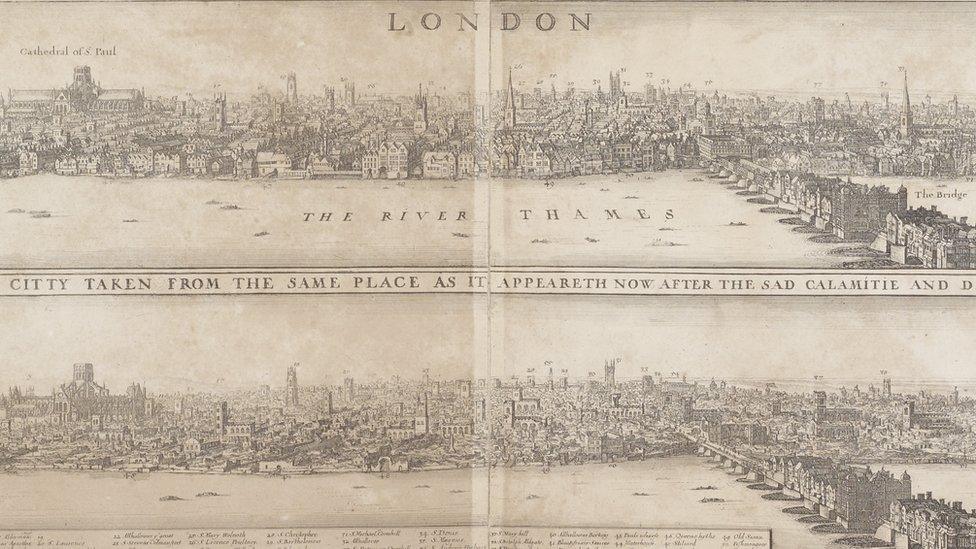

An illustration showing London before the fire, top, and below, after the fire

Birth of the insurance industry

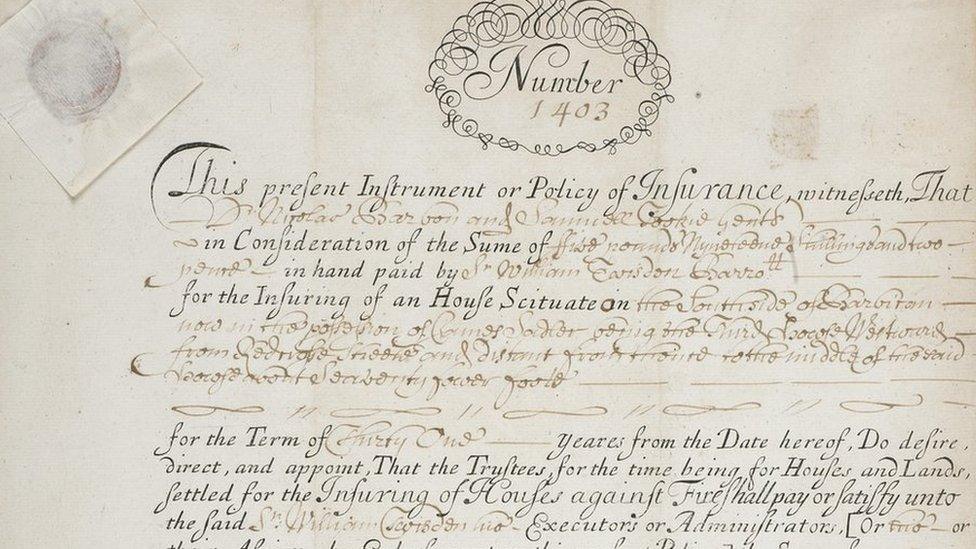

One of the first ever insurance policy documents, signed by Nicholas Barbon

The fire destroyed more than 13,000 homes at a time when insurance did not exist.

The Fire Court was set up to deal with property disputes and decide who should pay - and did so for a decade after the fire.

Physician Nicholas Barbon capitalised on the business opportunity, setting up the first insurance company, the Fire Office, in 1667.

His company even had its own fire brigade for those who had bought insurance and policyholders were given plaques for their homes displaying their policy number, so the brigade would know which fires to put out.

Further insurance companies were set up, including the Sun Fire Office, which was established in 1710 and is now the oldest insurance company in the world.

James Dalton, from the Association of British Insurers, said: "The Great Fire of London led to the modern insurance industry we know today."

The Hand in Hand Insurance Company fire mark, which belonged to Thomas Boules who lived near St Paul's Cathedral

Fire brigade

A fire squirt was like a large syringe, and would be used to shoot water at burning buildings

In 1666 there was no fire brigade, no hosepipes and no protective clothing. Each parish church had to keep equipment in the event of a fire - including buckets made of leather and fire hooks, which were used to pull down burning buildings.

An inventory from the same year shows the parish of St Botolph's, Billingsgate, half a mile from Pudding Lane, had 36 buckets and a ladder. But these proved of little use in the event of a fire which spread so fast.

A fire bucket, believed to be from 1666. The markings of the parish of St Botolph's, Billingsgate, are just about visible

Early fire engines were essentially a large barrel on wheels. They only delivered six pints of water per squirt, were hard to steer and unreliable.

After the fire, new rules were brought in and every parish had to have two fire squirts, leather buckets and other fire equipment.

The new designs for the City also included a requirement for a quayside to be opened up along the River Thames to make homes by the river accessible.

An example of a 17th century fire engine

Fire engines outside King's Cross station on July 7 2005

Finally, the Metropolitan Fire Brigade was formed, bringing with it new fire stations, a new uniform and a new rank system.

Now the London Fire Brigade, it celebrates its 150th anniversary this year.

The exhibition Fire! Fire! opens at the Museum of London on 23 July.