Grunwick dispute: What did the 'strikers in saris' achieve?

- Published

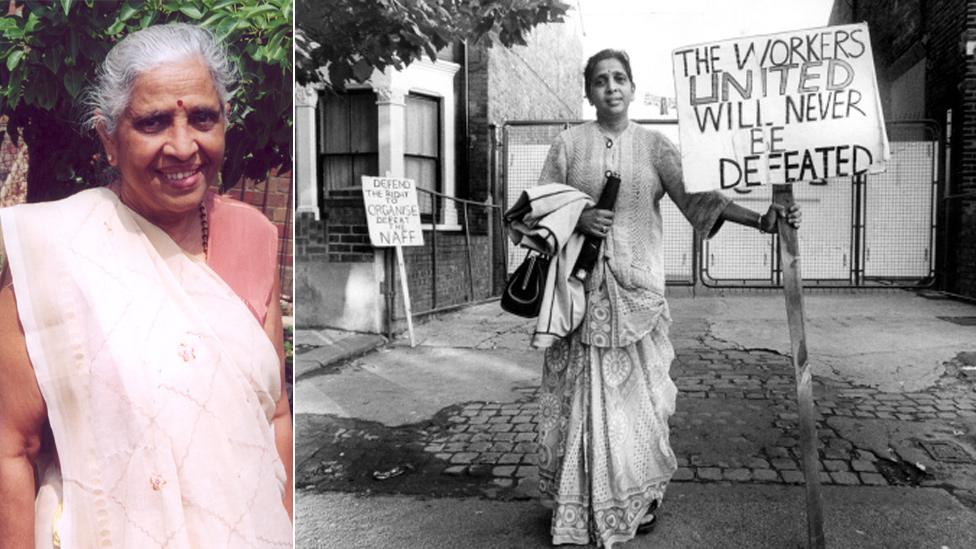

Jayaben Desai, pictured in 2001 and 1977

The long hot summer of 1976 saw Britain in the grip of a gruelling heatwave, struggling with a drought lasting for months. But it was not the only draining battle taking place. In north-west London, a group of South Asian women took to the streets in revolt at poor working conditions at the Grunwick film processing factory. Eventually more than 20,000 people joined in the protest.

The women behind the dissent eventually found themselves taking on not just the factory bosses but the trade unions that initially supported them.

So what is the story of the "strikers in saris"? It is a story not just of a groundbreaking movement, but of an extraordinary woman - Jayaben Desai.

In the 1970s, black and Asian workers were typically relegated to the lowest paid jobs, were often paid less than their white colleagues and were "more often than not, ignored by the trade unions," says Amrit Wilson, a writer and activist on race and gender issues.

Many of the women, originally from India and Pakistan, had been settlers in East Africa when it was under British colonial rule. They lived comfortable lives and worked in middle-class jobs such as teaching or administration.

When Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda gained independence, new governments adopted policies that discriminated against these Asian migrants. As British citizens they were entitled to settle in the UK and many decided to do so.

In London's unwelcoming post-war society, the only work they could get was low-paid factory work and manual labour.

The Grunwick factory, in north-west London, took on many migrant women workers, mostly Indian women from East Africa, who were considered to be "hardworking and docile," according to research, external.

On 20 August 1976, mother-of-two Mrs Desai walked out of the factory in support of a sacked colleague.

As she left, the line manager compared her and her colleagues to "chattering monkeys".

She replied: "What you are running here is not a factory, it is a zoo. But in a zoo there are many types of animals. Some are monkeys who dance on your fingertips, others are lions who can bite your head off.

"We are the lions, Mr. Manager."

Her son Sunil Desai, who also worked at the plant, helped her set up picket lines outside the factory. The pair began a passionate campaign to improve standards at the company and egged on many more workers to walk out.

Mr Desai remembers it as "a hot summer with hot tempers".

Mrs Desai, who died in 2010, said at the time: "They got more work out of us. Asians had just come from Uganda and they all needed work.

"So, they took whatever was available. Grunwick put out leaflets saying 'come and we will give you a job. We give jobs to everyone.'

"Door to door. When I went, a friend of mine followed. And soon they were full of Asians."

Hardworking the women may have been - but when roused, docile they were not.

Research by Dr Sundari Anitha, from the University of Lincoln, and Professor Ruth Pearson, from the University of Leeds, suggests that, while these women were "willing to accept jobs that had low status and low pay, they were unwilling to accept the degrading treatment that in those days was typically handed out to 'unskilled' non-white immigrants in workplaces".

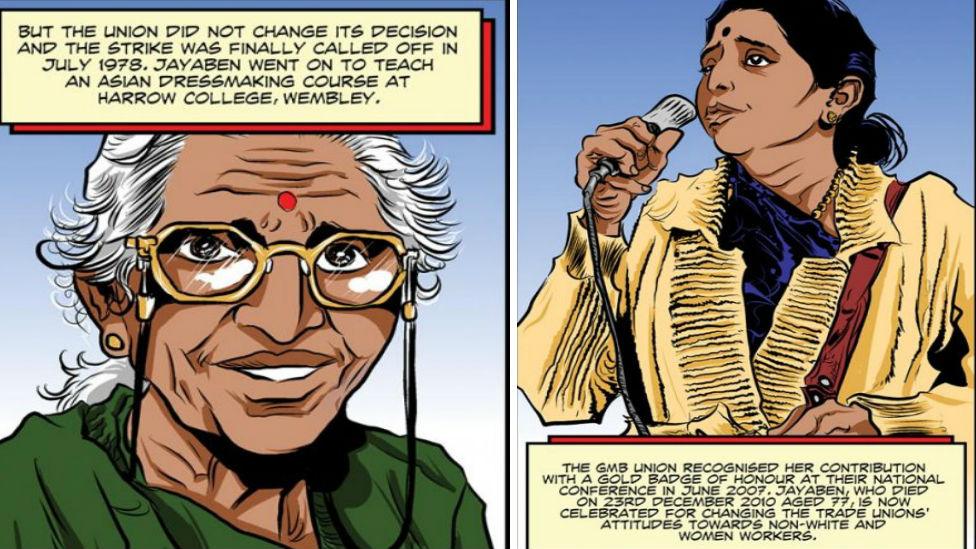

Dr Anitha and Prof Pearson have also produced a comic strip , externalabout Mrs Desai.

What was wrong with their workplace?

One protester described the managers as "being in a glass cabinet. They could see us, and if they called us into their office, the rest of the workers could see them, but could not hear what was going on.

"We used to work out of fear."

The workers decided that they'd had enough. They joined a trade union and began to make demands.

Grunwick refused to recognise they had joined a union and also refused to give them permission to do so - a position from which they refused to budge.

The 137 workers on strike were sacked.

After a few months picketing outside the factory, their cause was taken up by the wider trade union movement. By June 1977 there were marches in support of the Grunwick strikers, and on some days more than 20,000 people packed themselves into the narrow lanes near Dollis Hill Tube station.

The dispute rapidly escalated, culminating in pitched battles between mass pickets and police as the company bussed in other workers. Three of the Labour government's ministers - Shirley Williams, Fred Mulley and Dennis Howell - joined the picket line.

National Union of Mineworkers leader Arthur Scargill and striking colliery workers also joined in.

On a particularly brutal day in November 1977, when 8,000 people turned out to protest, 243 pickets were treated for injuries, 12 had broken bones and 113 were arrested.

Home Secretary Merlyn Rees, who insisted a heavy police presence was "necessary", turned up at the demonstration to appeal for calm but he was jeered., external

The conciliation and arbitration service Acas was forced to withdraw from the dispute because the Grunwick management refused to take part in mediation.

Eventually, both the TUC (Trades Union Congress) and Apex (the strikers' union), felt that the dispute could not be won and withdrew their support.

Yasu Patel, Jayaben Desai and Johnny Patel went on hunger strike

At first, Jayaben Desai and the strikers refused to be dictated to.

The long hot summer of 1976 was now in the distant past and - on a cold day in November 1977 - four stalwart protesters - Mrs Desai, Vipin Magdani, Johnny Patel and Yasu Patel - started a hunger strike.

Mrs Desai and her colleagues felt abandoned and disillusioned. As she said: "Trade union support is like honey on the elbow - you can smell it, you can feel it, but you cannot taste it."

But nothing worked and after two long years of struggle, the dispute ended in defeat for the strikers.

The workers who took action were never reinstated and neither did they win union recognition.

There is now little sign in the narrow streets of Dollis Hill that this was once the site of a long and bitter struggle, other than a small, barely noticeable plaque on the wall of the former factory commemorating Mrs Desai's actions.

Later this year a mural will be unveiled where the factory once stood, the funds raised by Brent Trades Council and local activists.

But did the Grunwick dispute have any lasting impact?

Although the strikers did not get their jobs back, some concessions relating to existing and future workers' pay and pensions were won.

However, the greater victory was arguably the message it sent about immigrant workers' place in society and their determination to stand up for their rights.

"The strike was a unique and transformative moment," says Ms Wilson. "It did not put an end to stereotypes of Asian women, but it certainly challenged them.

"This passionate assertion of strength, and the claiming of a newfound collective identity, bringing with it a sense of hope and new possibilities, arose not only from taking a stand as exploited workers but from collectively confronting racism at work.

"It was also, often, about winning a struggle against the patriarchy of the women's families and communities in order to go on strike in the first place."

There were other knock-on effects from the dispute. The mobilisation of the trade union movement in support of the women was one of the factors that contributed to the outlawing of secondary picketing, external by Margaret Thatcher's Conservative government of the 1980s.

And the period also saw the establishment of state databases of activists, for the purposes of surveillance. Special Branch even had files on the Grunwick strikers and some of their supporters, including Jack Dromey MP, who was at the time the secretary of Brent Trades Council.

He said that the lasting legacy of the strikes was the example set by Mrs Desai.

He said that, in generations to come, "people will look back at a woman who was truly one of the most remarkable women to ever have fought for workers' rights".