Last call: What's happened to London's nightlife?

- Published

Some 50% of London's nightclubs have closed down according to London mayor Sadiq Khan

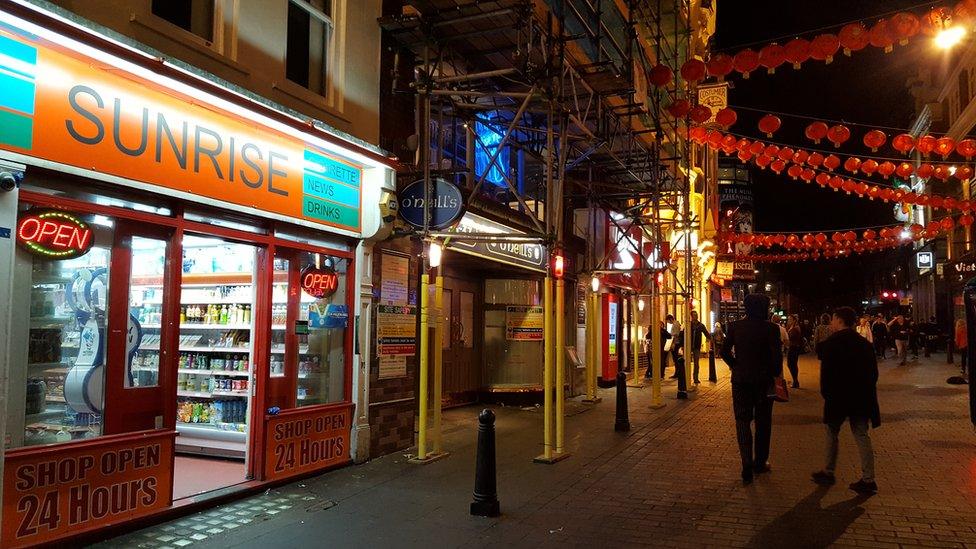

Another night Tube means more options for Londoners to exploit the nightlife of one of the world's greatest cities. But with half of its nightclubs closing in the last five years will there actually be anywhere left to go "out out" at 2am on a Sunday?

The Tropicana club in Covent Garden is a rarity.

The "rum-soaked tropical paradise", which can be found down a largely anonymous street in central London, is said to be the first "brand new" nightclub to open in the centre of the capital for a decade.

In contrast, during the past five years the number of nightclubs across all of London's 33 local authorities has decreased by 50%, according to the Mayor's office.

Bars, pubs, social and comedy clubs have also seen numbers drop.

And music venues do not fare much better. Of the 430 that traded in London between 2007 and 2015, only 245 are still open, research by the London Assembly suggests.

There was an outcry when Fabric nightclub lost its licence

The Astoria in central London hosted artists including David Bowie, Radiohead and Muse

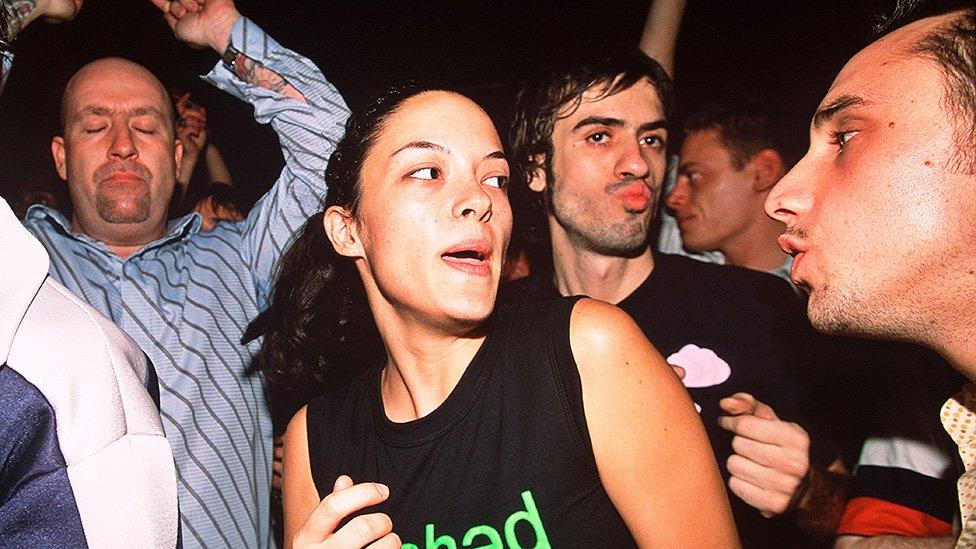

The closure of one of Britain's best-known nightclubs Fabric, which lost its licence after two people died from drug overdoses in the club, provoked a flurry of questions about the future of UK's club culture.

But the picture appears particularly bleak in the capital, where Fabric was just the latest in a long line of closures.

Cable at London Bridge went in 2013 when Network Rail took back possession and Turnmills, the first club to get a 24-hour licence, closed in 2008 when the lease ran out. Offices are now on the site.

"The first reaction when there's a problem by city officials is often 'ok we have to stop this now'," says Amsterdam's night mayor Mirik Milan, who is in charge of boosting the Dutch city's night economy.

"When you suddenly stop something, then you can also kill an industry with it - and this is something that I think is happening with London."

'Out out'

to be spending your evening in a nightclub, rather then just going to the pub for a beer

Source: Urban dictionary submission by Chris Wayman

Figures obtained by BBC News show there are only 30 nightclubs or bars trading with a 24-hour licence in the whole of London.

Westminster Council, which covers much of central London, has three nightclubs with this licence, while Camden, long known for its nightlife, has none.

"There should be places - this is London - but there is a massive lack of places which are open late. That's a real shame," says the founder of Secret Cinema, Fabien Riggall.

"It's so sad what's going on with London at the moment. There's such a lack of support in these cultural spaces."

Lambeth Council, which also covers large swathes of central London by the River Thames, says there are 96 businesses which hold a 24-hour licence, but could not provide a breakdown by type.

The majority of 24-hour licences are held instead by supermarkets and off-licences. Many bars open until 02:00 to 03:00, but the figures obtained by BBC News show how many can trade right into the early hours.

Dan Beaumont, the co-owner of Dalston's Superstore nightclub, is not surprised by the lack of places with 24-hour licences. The reason? He says it's extremely difficult to meet local authorities' conditions that form part of the Licensing Act, external.

He believes nightclubs have become the "battleground for lots of competing agendas" and that hugely inflated real estate prices, the demand for housing and pressure on local authority and police budgets have all contributed to a climate which makes it very difficult to operate in.

"As the pressure mounts on some of these institutions, it seems that clubs are pretty easy targets," he says.

"As an operator it [Fabric's closure] is terrifying and I think everyone is very nervous because it does set a very scary precedent.

"But it's also an opportunity to figure out what went wrong and to try to take a step back to see how we can do things differently and how we can come back from this, not only as Londoners but also as local authorities, as police, as DJs, as artists."

One issue to overcome is licensing. In London there are 33 local authorities, all pursuing their own specific policies. There is no specific plan for London as a whole.

Some boroughs, such as Hackney and Tower Hamlets, operate a late-night levy - this means nightclubs help to pay for policing and clear-up costs.

And it's an "inflexible licensing policy" that is the biggest problem, according to Kate Nicholls, chief executive of the ALMR - the national trade body representing pubs, bars and restaurants.

"We're a world-class city and we're governed by little town halls and bureaucrats who believe they know what's best for customers," she said of Fabric's closure.

"Unfortunately, those making the decisions about the vital and vibrant part of London's economy seldom have any experience themselves of going out, particularly late at night."

"Too often we see culture two-dimensionally; we see it as the Royal Opera House and not the bar opposite."

Most of the businesses with a 24-hour licence are supermarkets, off-licences and petrol stations

Londoners now have more options for night time Tube journeys

With many closed venues being turned into property, developers have insisted it is local councils that are responsible for closing nightclubs and deciding what happens to particular sites.

And when more people move in to areas with an existing night time economy, the inevitable complaints about noise follow.

This is an issue the Ministry of Sound in Elephant and Castle successfully resolved when it encouraged a developer to improve sound proofing for a new 41-storey building.

About 100,000 people have used the Night Tube since its launch in August

But for residents who live near nightclubs the noise, "streams of urine" and rubbish is not pleasant.

Mathew Hill, who lives on a residential road just off Hackney high street, says: "It's not the nicest. If you had the option I think most people would say they wouldn't want to walk through that in the morning."

Mr Hill has lived in the area for a few years, but is now moving because he believes "you have to be a certain age and [of] a certain mindset to really enjoy what's going on here".

"I think most of us get to the point where it's not for us any more," he adds. "The issue - with London being London - is pretty much every residential street has a commercial street on the end of it, so if you can't accept it you have to move away."

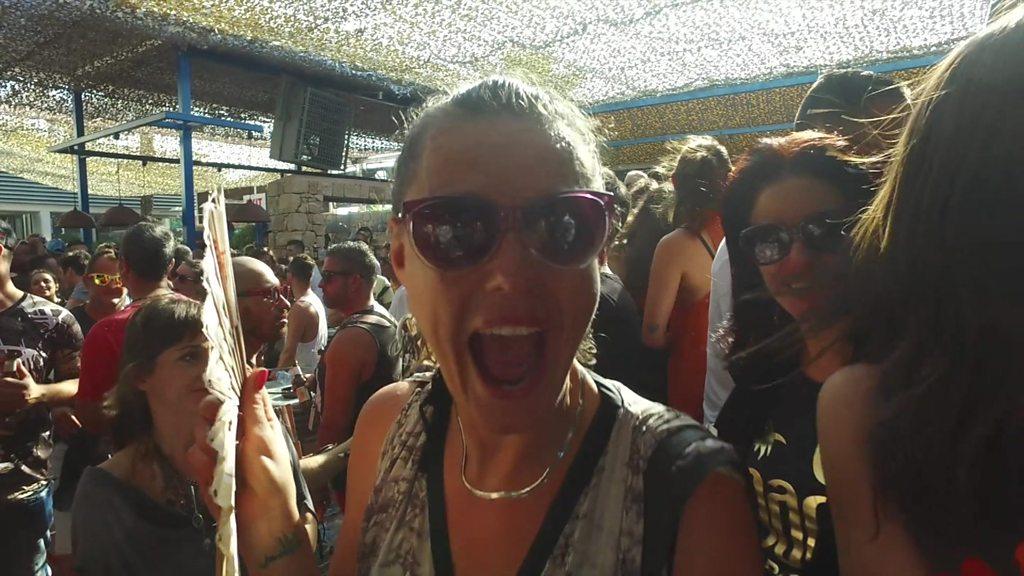

But London's nightlife is also facing a threat from a cultural shift that it didn't expect - an entire generation choosing increasingly to stay in, rather than go out.

Low disposable income plus social media, Netflix and music streaming websites have all made it difficult to get millennials - people born after 1981 - out of the house.

But Mr Riggall, whose Secret Cinema events - which offer a mix of film screening, live performance and audience interaction - have grown into a cultural force, believes the audience is still there.

"I'm not trying to criticise certain industries' work, but sometimes people get a little unadventurous when putting on experiences, a club night or whatever, and go back to the old days where people went out and dressed up and going out was a big occasion," he says.

"There needs to be a reinvention; make it an experience, colourful and magical and different and people will come."

Amsterdam's night mayor's plea to make 'London proud again'

Live music is not immune to change either. Earls Court shut in 2014 to become flats, while the Astoria - scene of many a career-defining gig for bands on the rise - had to make way for Crossrail.

But gigs continue to offer an "experience" for music fans, so despite the closure of a number of venues Time Out London's music editor Oliver Keens believes they are not under the same threat as nightclubs.

"They rarely apply for late licenses," he says. "They are able to control the flow of crowds better than clubs as there isn't a constant churn of people coming and going all night, a major reason clubs fall out with residents, police and councils."

Although there are few new music venues, he says places such as Union Chapel or Islington Assembly Hall adapt to become music venues to fill a void.

"While it's true that bookings are skewing to an older, safer market like never before, at the same time Spotify and YouTube, as well as radio and dare I say print media, have fostered a whole new enthusiasm among gig-goers," he adds.

"Take Skepta, for example, who sold out his December show at Alexandra Palace in two hours, way before he won the Mercury prize."

Nightlife around the world

New York and Copenhagen run a subway service 24/7, and Berlin, Vienna, Stockholm and now London run one at weekends.

Paris, Toulouse, Zurich and Amsterdam all have night mayors.

Berlin: Clubs have banded together to protect their businesses and have instigated policies stating that new arrivals to an area cannot complain about noise that predated their move

Hong Kong: Bars are often open into the early hours, but unregulated stores selling cheap alcohol is putting them under pressure

New York: Clubs can stay open all night, but must stop selling alcohol between 04:00 and 07:00

Tokyo: Clubs can now apply for licences to stay open until 05:00 after a 67-year-old law was overturned

Sydney: To counteract noise complaints, the government introduced strict guidelines of no more customers after 01:30, and no alcohol beyond 03:00. This has devastated local clubs, with footfall plummeting by 82%, external.

So what's being done?

London mayor Sadiq Khan is keen to address the issue and is about to appoint a night tsar, in particular focusing on how local authorities, Transport for London (TfL), venues and the police can work together.

It is also hoped the Night Tube, which TfL claims could add £360m to the economy over 30 years, external, will reinvigorate the night-time economy as London looks to become a true 24-hour city.

New York, the 'city that never sleeps' is known for its night life

One place that can already claim that title is New York.

Aided by a 24-hour subway system, the city's nightlife does not truly get going until past midnight, according to Time Out New York's restaurant editor Christina Izzo.

"All-day, all-night amenities go beyond boozing," she says. "There are 24-hour gyms and fitness clubs, 24-hour hair salons and massage parlours, 24-hour supermarkets, pharmacies and laundromats. You can pretty much run any of your usual daytime errands in the witching hours in NYC if you so choose.

"I think having a continuous loop of activity and myriad late-night options are just encoded in New York's DNA."

And the city does not appear to be following London's trend of closures.

"The New York venues that have been shut down have been more of the DIY sort - I'm talking barely-legal music venues or Brooklyn warehouses moonlighting as a dance club.

"But in terms of on-code venues, late-night bars and restaurants with kitchens operating into the wee hours, I haven't seen a slowing down in the opening of those type of spaces."

With the Jubilee Line joining the Central and Victoria lines in going 24-hours at weekends, London could challenge New York's crown.

For now, it's a beach-themed nightclub in Covent Garden that's offering signs of hope for London's night-time economy.

Anthony Knight, marketing manager at the Tropicana club, says the Night Tube has already seen revenue increase by 22% at its other venues.

"With the introduction of the 24-hour Tube, there's a lot more confidence in people going out later at night, which in turn inspired us to open this brand new venue," he says.

"People are staying out later, they're spending a lot more money, and in turn that gives us the confidence in our late-night operations."

- Published5 October 2016

- Published10 August 2015

- Published7 September 2016

- Published20 September 2016

- Published7 September 2016

- Published20 September 2016

- Published1 August 2014