London nail bombings remembered 20 years on

- Published

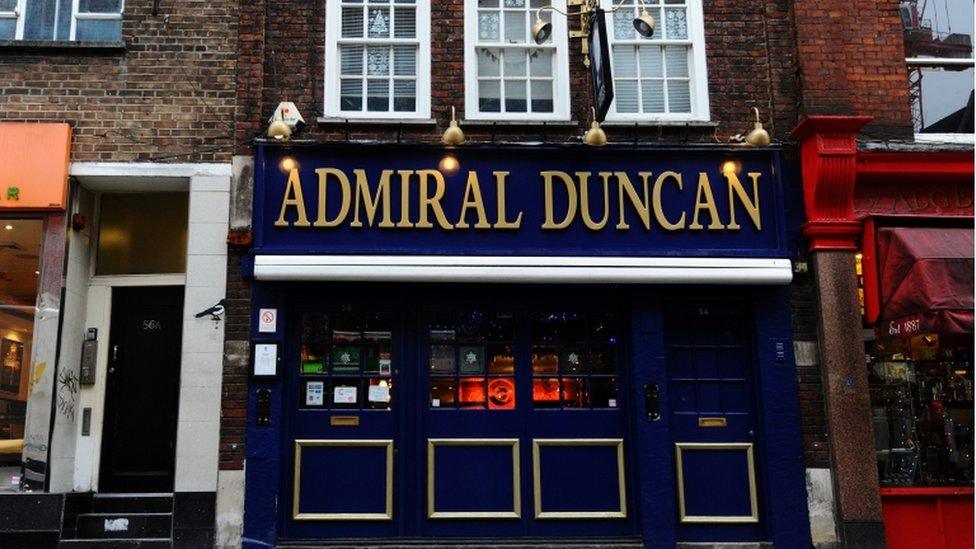

The aftermath of the deadly attack at the Admiral Duncan pub in Old Compton Street

On 30 April 1999, a third nail bomb attack inside two weeks was carried out in London, killing three people and injuring dozens more. It was the final bombing by David Copeland, a self-confessed racist and homophobe.

Twenty years on from the explosion at the Admiral Duncan pub in Soho, those who were affected by the 22-year-old's campaign of hatred have been speaking about their experiences.

Dozens were injured in the first explosion outside a Brixton supermarket

Sandra Mills was walking past the Iceland supermarket near Brixton market in south London late in the afternoon of Saturday 17 April 1999 when a bomb went off, "sending thousands of nails flying in all directions".

"I remember hearing a loud, deafening blast, like a huge gust of wind that blew all the windows out," she said.

"My heart sank to my stomach in sheer panic and I just stood still.

"After what seemed like an eternity of silence, I saw an injured man lying in the road which was covered in glass. I ran to his aid and saw he had nails lodged in his legs.

"The attack just came out of nowhere. It was so frightening."

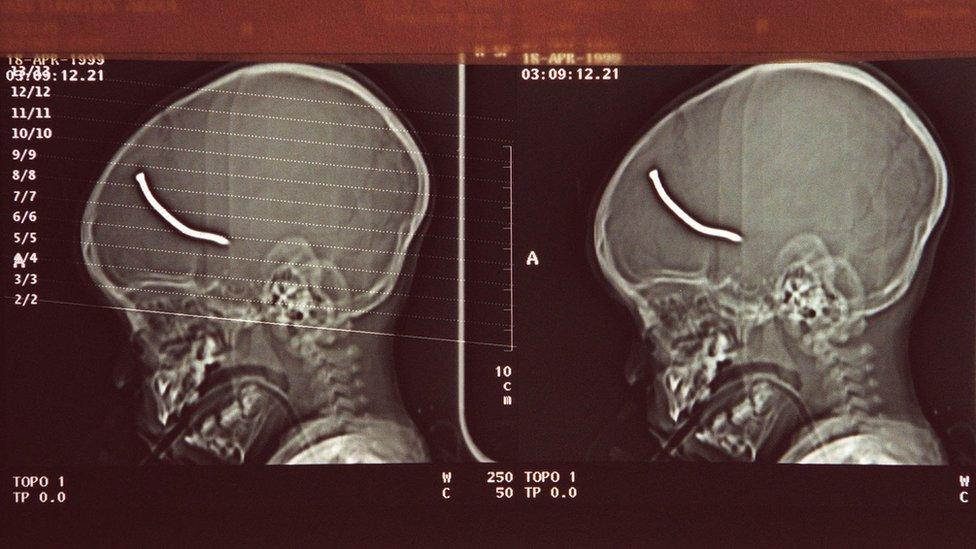

Forty-eight people were injured in the bombing, which was intended to target Brixton's black community. One of the victims was a one-year-old boy who was left with a nail lodged in his skull.

Among the victims of the first attack was a 23-month-old boy, whose skull was pierced by a 2cm nail

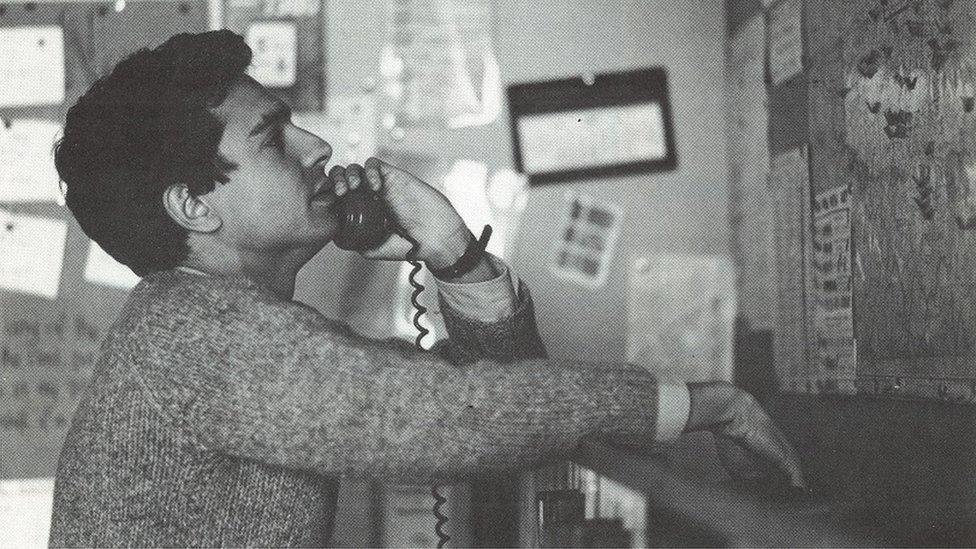

Police worked until they dropped in a bid to find the perpetrator, says Sir Hugh Orde, who was the on-call commander for the Met Police in south London that day.

"Officers ploughed through miles and miles of videotape, 24 hours a day," he said.

"When I received the call on 17 April, the first question I asked was who on earth would put a bomb in the middle of a market on a busy Saturday afternoon?

"My gut feeling was that the only logical explanation for this attack was racism."

His instinct proved to be right.

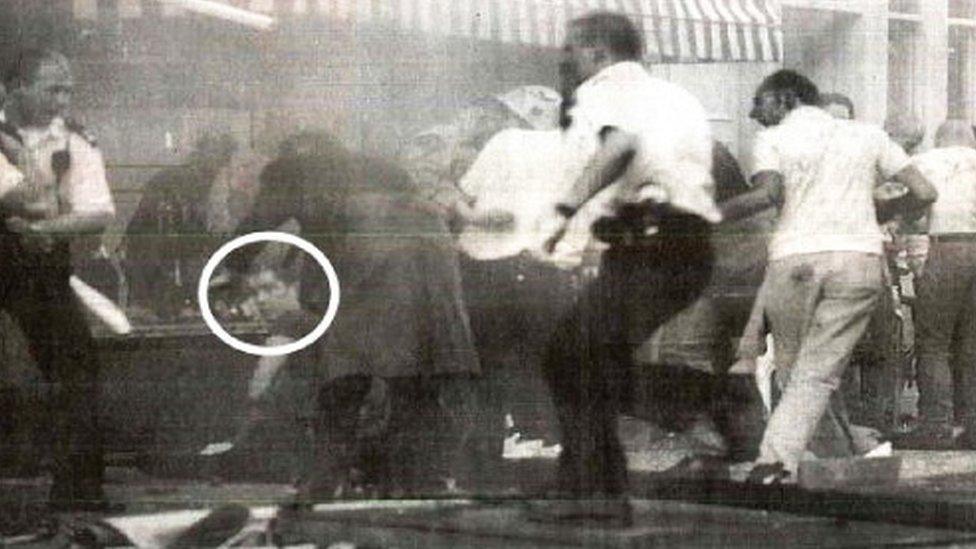

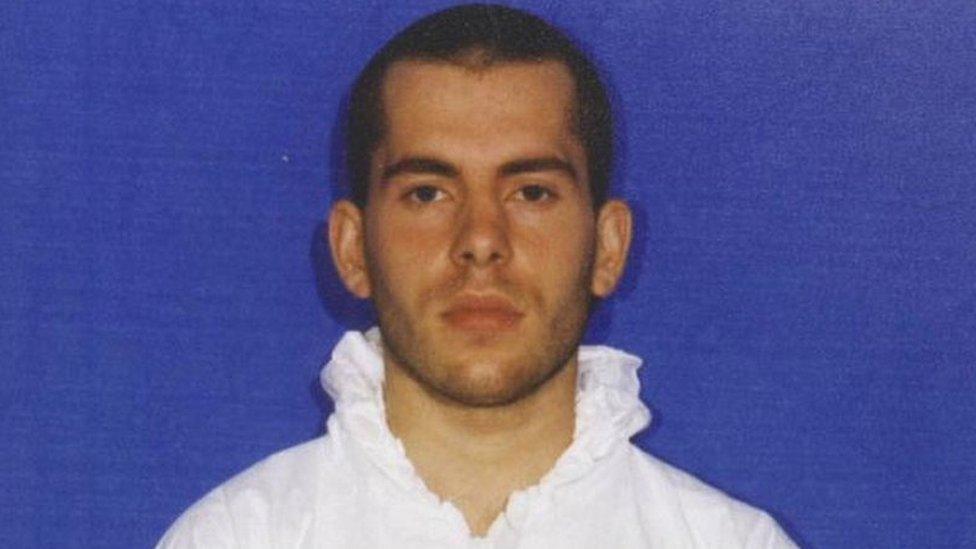

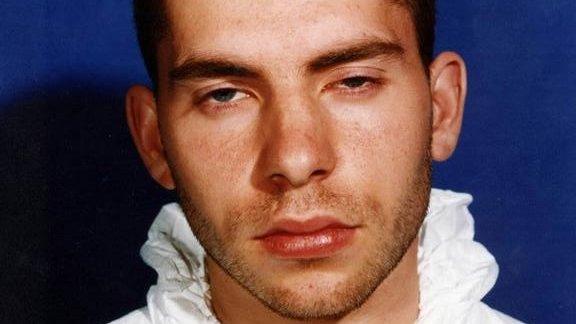

David Copeland was caught on camera in Brixton about 90 minutes before the explosion

A week after the Brixton attack, the bomber who would later be identified as Copeland went on to target the centre of the capital's Bangladeshi community in Brick Lane, east London.

A stroke of good luck meant that a sports bag containing a second homemade device went off inside the boot of a car - a passerby had found it in the street and put it there for safe-keeping.

While he was away from the car, phoning the police about what he thought was lost property, the device exploded.

Copeland had actually intended to target Brick Lane's busy market day, which he thought was a Saturday. In the event, the street was much less crowded than it would have been had he left the bomb on the Sunday.

Emdad Talukder was left covered in blood when the bomb exploded

Emdad Talukder was near the scene when the device went off at 18:00 BST, throwing debris from the car "four storeys high".

Mr Talukder, who had been walking along Brick Lane, told BBC Newsnight the car's doors flew up "like pieces of paper" and a shard of glass hit him on the head.

"The glass was about four inches long and immediately I was showered with blood. My whole body was a sea of red."

He said he would never forget the fear he saw in people's eyes as they ran.

"People had no idea where to go, or how to save themselves."

BBC Newsnight looks back on the three nail bombs that shook London in 1999

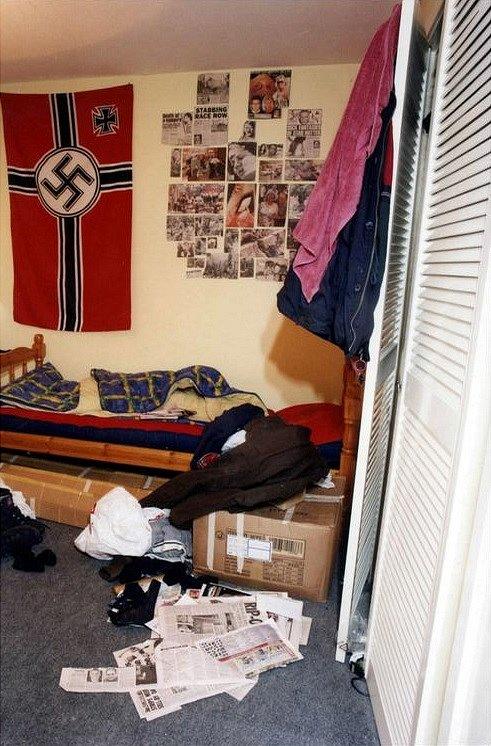

When Copeland was arrested a week later, police discovered a Nazi flag hanging on his bedroom wall along with clippings of the newspaper coverage of his attacks.

Mr Talukder was one of the people visible in the grisly collage on Copeland's wall.

"Within all these pictures, my picture was very prominent," Mr Talukder said.

"I stared at it and just thought 'oh my goodness'.

"It's still a nightmare."

A Nazi flag and newspaper clippings showing the aftermath of the bombings were found on Copeland's bedroom wall

The final bomb, containing 1,500 nails, went off on 30 April at the busy Admiral Duncan pub on Old Compton Street in Soho, central London, where the clientele was predominantly gay.

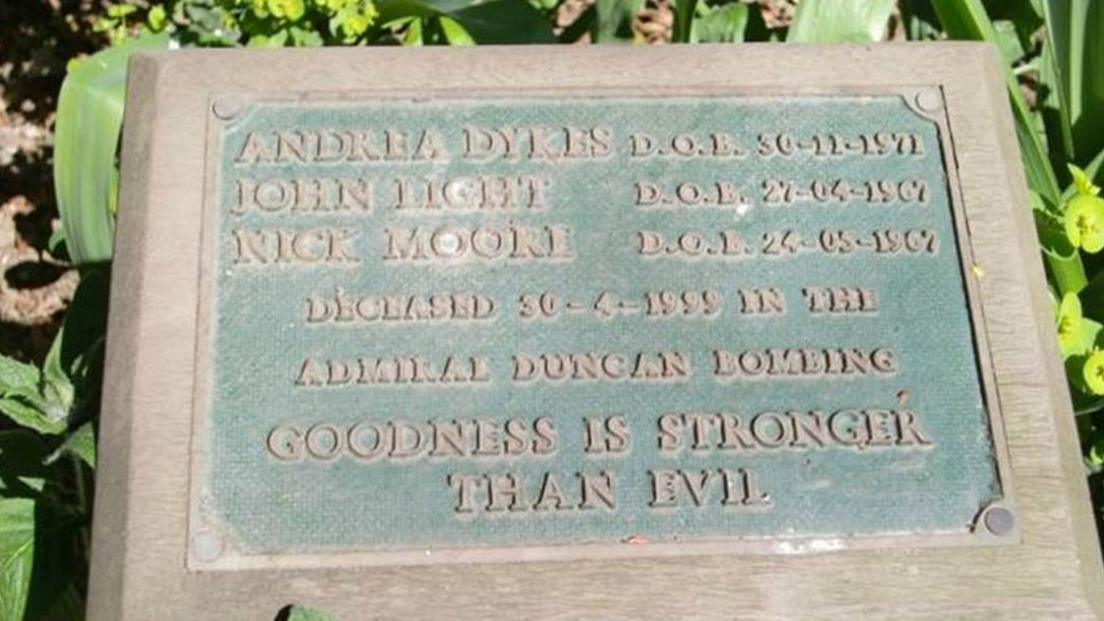

Andrea Dykes, 27, John Light, 32, and 31-year-old Nick Moore were killed in what proved to be the last attack of the two weeks of terror.

More than 70 people were injured in the blast, some of them very seriously.

Jonathan Cash (circled) shortly after the explosion

Jonathan Cash, then 30, was at the Admiral Duncan waiting to meet friends.

"My foot touched a large sports bag which was on the floor," he said. "I ordered a drink and, thinking about the bag, assumed it belonged to someone. I can remember weighing up the possibility that it might be a bomb thinking, 'but these things only ever happen to other people'."

The bomb exploded at 18:37.

"The table I put my drink on, fixed to the floor, had gone," he said. "I couldn't see more than a few inches in front of my face because of the thick, acrid smoke."

"The next thing I knew, I was on my hands and knees in front of a shop window. I stared at my reflection, unable to to recognise myself. My hair was thick with yellow dirt. I noticed I had left a trail of blood behind me, but I wasn't aware of any injuries.

"I remember a girl in her early 20s appeared from a neighbouring pub, grinning with a pint in her hand."

He told Newsnight that he heard the woman use a homophobic slur and tell someone she "wanted to get a better view" of the injured.

Two decades later, Jonathan said he still gets anxious if he enters a crowd.

Survivors comfort one another after the bomb attack on the Admiral Duncan

Scott Terry had just finished a shift at the Royal Mail head office near Oxford Street and was inside the Admiral Duncan when the bomb exploded.

Blinded by dust and shrouded in smoke, he lay injured and on fire in the street having been hurled from the pub by the blast.

"I looked at my legs and all I could see was blood - lots of it," he said. "I was in so much pain that I held my breath and wished to die quickly."

Mr Terry was badly burned and had 74 nails embedded in his body - nine nails remain in his spine to this day.

He was kept in an induced coma for six months. When he emerged, memories of the blast swiftly returned.

"I later found out I was literally standing on top of the bomb," he said.

"I remember screaming out 'what is happening to me?' It felt as though I was standing in water and my fingers were in a plug socket.

"It was all a panicked blur, but I do remember a paramedic holding me and telling me to stay with him. Then it all went black."

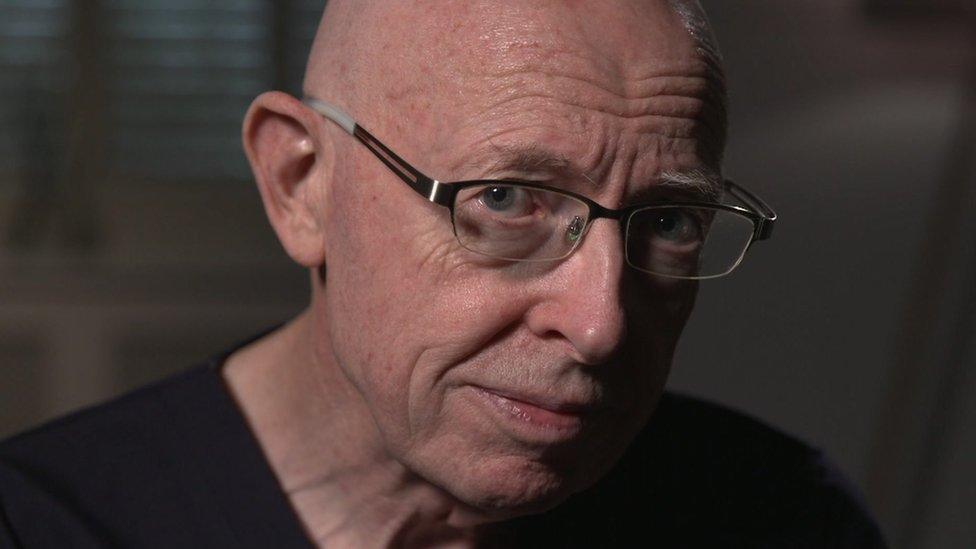

Prof Gus McGrouther said some victims were brought into hospital with partially-amputated legs

Prof Gus McGrouther, the on-duty consultant who treated the Soho survivors at University College Hospital, described some of the injuries as worse than those seen in IRA attacks.

He told BBC Newsnight there was a tremendous desire on the part of hospital staff to reverse the evil of Copeland's act.

"As the bomb was placed on the floor, there were a lot of bad leg injuries. There were people coming in with their legs partially amputated," Prof McGrouther said.

After emerging from his coma, Mr Terry was transferred to a burns unit and had to learn to walk again.

Although he feels lucky to have survived, he still faces frequent obstacles.

"Every time I go to an airport I have to show a doctor's letter to prove I have metal in my body," he said.

"Every time I shower and every time I look in the mirror, I look at my scars and think of what happened. It will never leave me."

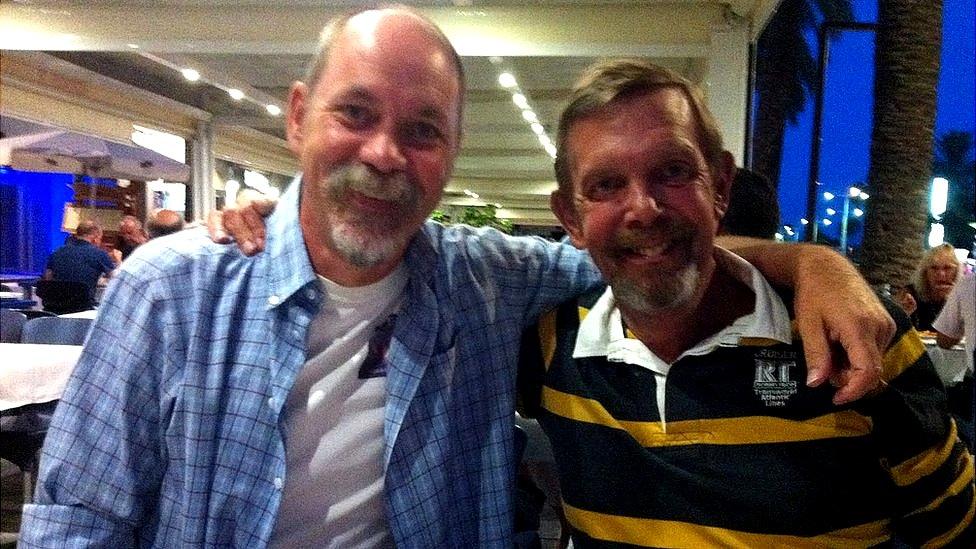

Mark Tullett (centre) was drinking with his friend Kath (in the vest top) and boyfriend Tony (in the denim jacket) when the bomb went off

Mark Tullett was enjoying a few pints in the Admiral Duncan with his partner Tony and friend Kath when the pub suddenly went black.

What should have been an enjoyable Friday evening at the start of a bank holiday weekend became a nightmare.

"We fell through the door, looking like refugees, covered in dust and splinters," Mr Tullett said.

"Had we been just a little slower in getting served, we could so easily have been the parts others would have scrabbled over on the floor."

It was not until a few days later that Mr Tullett realised he had come face to face with the bomber on the night of the attack.

"I remember a young man at the bar slamming down his pint next to me before grunting something and leaving," he said.

What Mr Tullett could not have known was that this drinker was the man who was already responsible for two explosions in London - and that he had left behind a bag containing a handmade nail-bomb.

Mr Tullett went on to marry Tony

"Having been served, I grabbed my pint and moved deep inside the pub where Tony was waiting. We'd had no more than a few gulps of our drinks when it happened."

While the psychological impact of the attack has faded with time, whenever the bombing is mentioned Mr Tullett's stomach lurches.

"Each year as the anniversary comes around, the memories flood back of that night and the aftermath of a terrible weekend.

"It's not something I will ever be able to think about without feeling upset or stressed."

Gary Fellowes saw a poster in the toilet at the Admiral Duncan saying "Bombs Beware" just before the explosion

Gary Fellowes remembers it being a warm and sunny day when he arrived at the Admiral Duncan at about 17:30.

"I remember seeing a poster in the pub toilet saying 'Bombs Beware' - of course it was not long after Brixton and Brick Lane had been attacked."

Mr Fellowes, then 39, had been drinking at the back of the pub near the jukebox for about an hour when he saw "a big flash - like a camera taking a picture".

The Admiral Duncan pub is holding an act of remembrance on the evening of Tuesday 30 April

"The pub went black and fell completely silent. No screams, no shouts. Just people still like statues in shock.

"I remembered seeing the poster in the toilet. It was only then that I was certain that a bomb had gone off."

With a "sunbed-red face", a blackened shirt and a nail embedded in his boot, Mr Fellowes was fortunate only to receive minor injuries.

But he said there was a point while trying to get out of the Admiral Duncan that he feared he wouldn't make it out alive.

"I just thought about all the smoke I had inhaled, and being an asthmatic I thought I might not make it.

"I just headed towards the light that seemed to be at the end of a very dark tunnel."

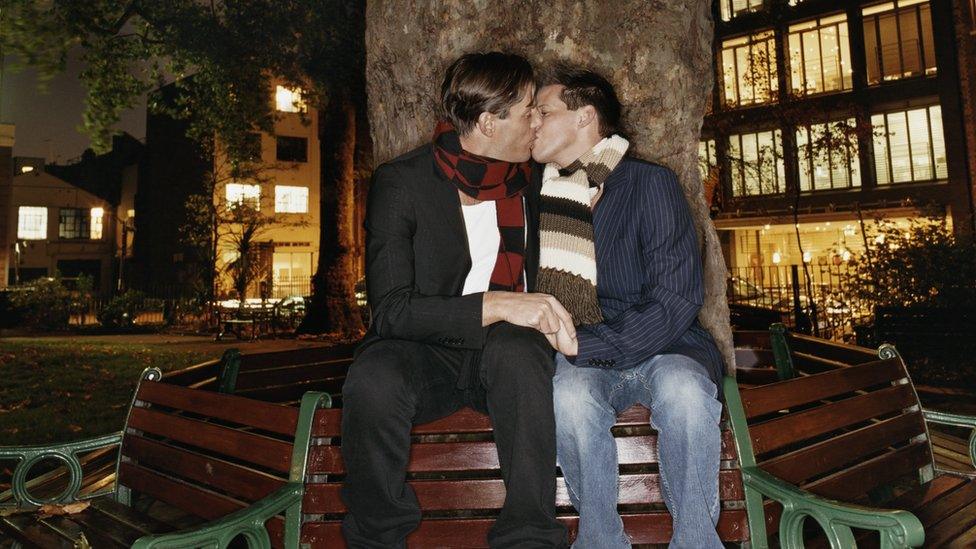

In the years Copeland has spent in prison, the age of consent has been equalised, same-sex couples have won equal adoption rights and gay marriage has become legal

Timeline of events:

17 April 1999 - A nail bomb explodes in the centre of Brixton just before 17:30, injuring 48 people.

24 April - A second nail bomb goes off in Brick Lane at 18:00. Thirteen people are injured.

29 April - Detectives issue an image of a young white man who is their prime suspect in the Brixton attack.

30 April - At 18:37, a device explodes in the Admiral Duncan pub in Old Compton Street. Three people die and 79 are injured.

1 May - Police raid a house in Cove, Hampshire, where they arrest a man and seize explosive materials.

2 May - David Copeland, 22, is charged with three counts of murder and three counts of causing an explosion in order to endanger life.

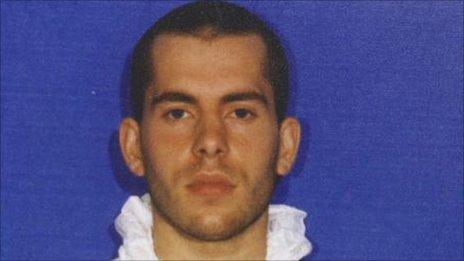

Copeland, pictured in 1999, will be in his 70s before he is eligible for parole

June 2000 - Copeland - a self-confessed homophobic Nazi who hoped to "set fire to the country and stir up a racial war" - is given six life sentences.

He is told he will spend a minimum of 50 years in prison.

'The First Domino', a play written by Jonathan Cash inspired by his experience of the bombing, will be rebroadcast on Radio 4 Extra on Thursday 2 May at 21:00.

- Published28 October 2015

- Published4 March 2019

- Published29 April 2013

- Published28 June 2011