Paddington rail disaster: Survivor fears safety 'could be slipping'

- Published

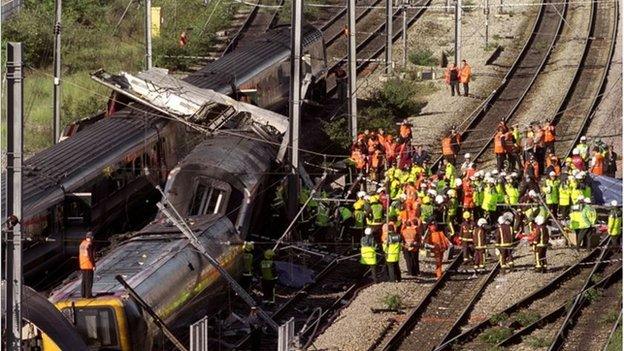

More than 500 people were injured when two trains collided head-on after a train driver missed a red signal on 5 October 1999

A Paddington rail disaster survivor has said he fears safety standards may be slipping 20 years after the crash.

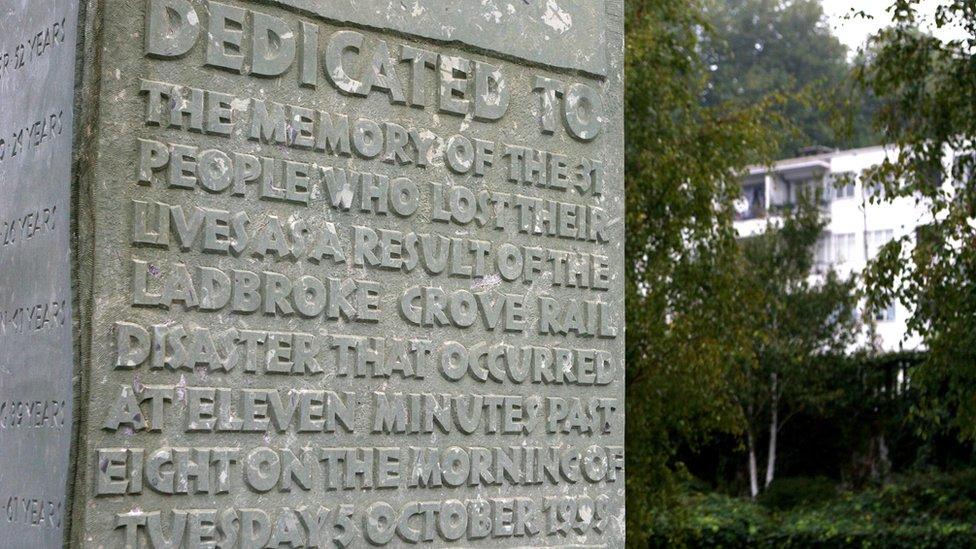

Thirty-one people died when two trains collided almost head-on after a driver missed a red signal on 5 October 1999.

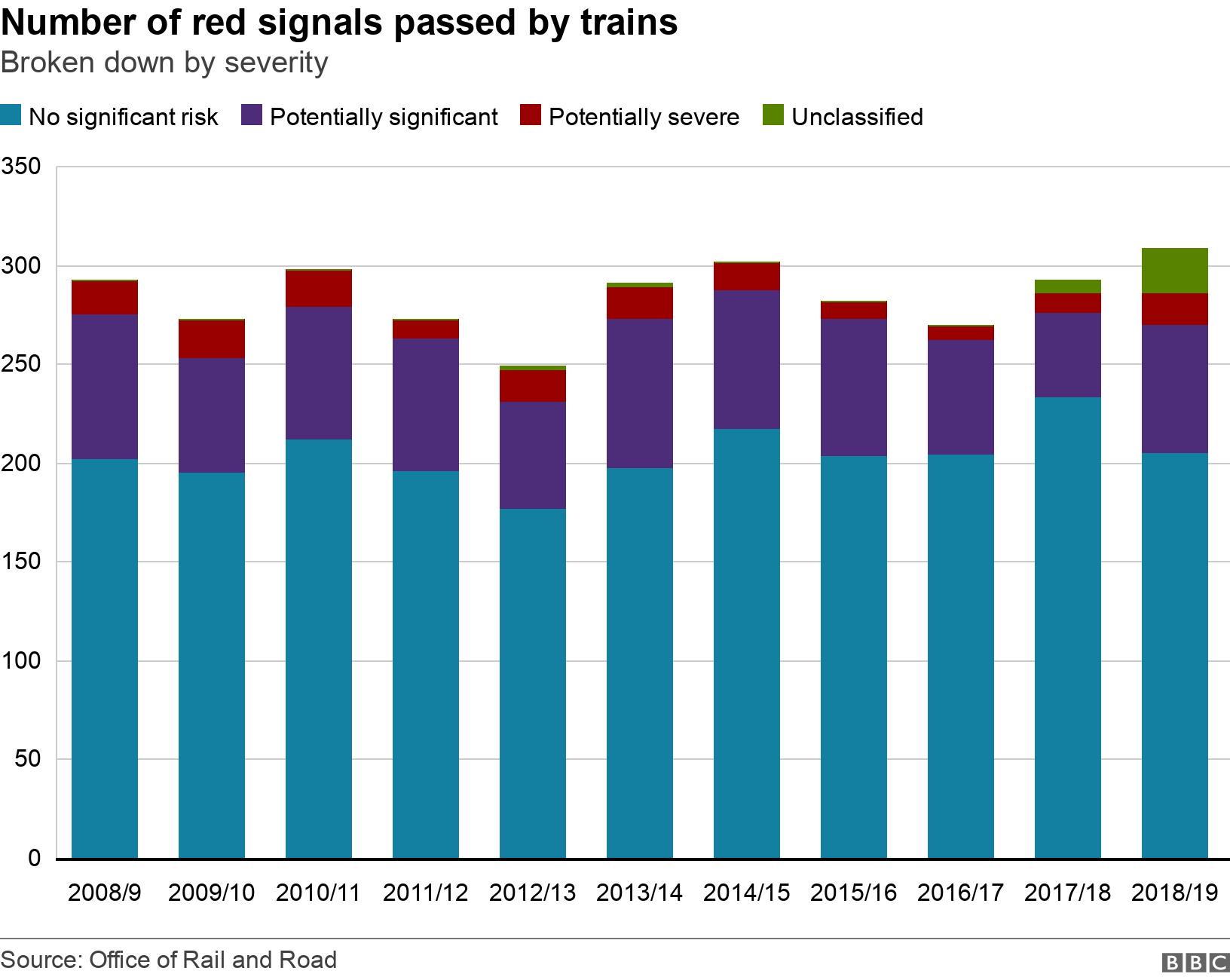

In 2018-19, 304 trains passed through red signals, a 10-year high, according to official data for England, Wales and Scotland., external

"The risk now is that standards might drop," said Jonathan Duckworth, chair of the Paddington Survivors Group.

He was one of 227 people hospitalised when his First Great Western train collided with another train at Ladbroke Grove, about two miles from its destination of Paddington, at a combined speed of about 130mph.

'Continually learning'

In the 10 years following 1999 the number of Signals Passed at Danger (Spads) more than halved, from 593 to 273.

But the number has begun to creep up again and July saw 41 Spads, more than one a day, the highest number in a single calendar month for 12 years.

The UK has "one of the safest railway networks in Europe", rail minister Chris Heaton-Harris said.

He added: "We are continually learning how to make our railways safer, that is the legacy of a terrible disaster such as this.

"But disasters could happen any time. That is why one of my many jobs is to ensure we have safety hardwired into every decision that they make."

Emergency services freed 20 trapped survivors and took eight days to clear the scene of the crash.

A 70-metre wall of fire engulfed the two trains as fuel caught alight following the collision at about 08:10 BST on a Tuesday morning 20 years ago.

"We went through a massive fireball. I could feel the heat coming through the windows," Mr Duckworth said.

"I had no idea what was going on. I thought perhaps it was a bomb.

"We basically derailed and overturned, so our coach ended up on its side.

"There was a bit of a battle to get out. It's not easy to get out of an overturned carriage."

When he got out Mr Duckworth saw "smoke billowing out from charred carriages" lying on their sides as police and rescuers swarmed over the wreckage to try to locate trapped survivors.

It would take days to remove all the bodies from the wreckage.

Jonathan Duckworth said the crash gave him PTSD and ruined his career

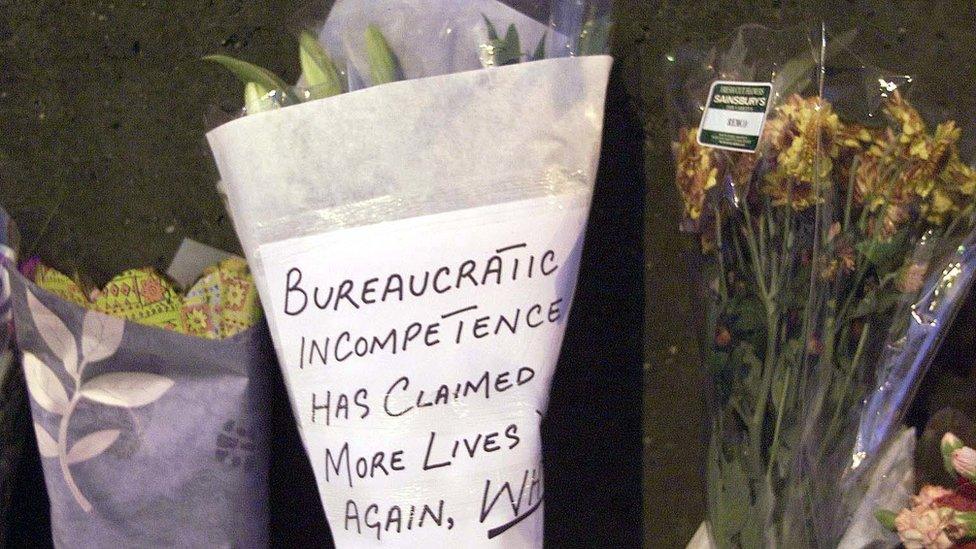

The outcry that followed led to the biggest-ever safety reform of the country's rail network.

A series of complex public inquires culminated in two reports by Lord Cullen.

The inquiry found the crash was caused by the Thames Trains service travelling from Paddington passing through a red signal.

But Lord Cullen concluded the crash was the culmination of "a catalogue of failures to act".

He levelled severe criticism at Thames Trains for its "slack and less than adequate" safety culture. It was fined £2m in 2004.

Railtrack, Network Rail's predecessor, was accused of a "lamentable failure" to introduce safe signalling systems in the entrance to Paddington station.

Lord Cullen levelled severe criticism at the rail industry for "a catalogue of failures to act" on known rail safety problems

Paddington was supposed to be a watershed but a series of fatal rail crashes followed at Hatfield in 2000, at Selby in 2001 and at Potters Bar in 2002.

The Paddington Survivors Group, set up to help victims and bereaved families cope with trauma, campaigned to improve rail safety.

Under pressure from the group, a train protection warning system that halted trains passing through red signals became industry standard.

The group worked with the Office for Rail and Road and Network Rail to reorganise the industry in the wake of the crash.

Network Rail, which superseded Railtrack in 2002, was fined £4m in 2007 for health and safety breaches in the run-up to the Paddington crash, after years of campaigning by the survivors group.

In addition to July seeing the highest number of Spads for more than a decade, the past 12 months has seen 10 trains pass red signals and reach the "conflict point" - the position along the track at which a collision could theoretically take place.

The average over the past five years has been between four and five.

Carriages overturned as the two trains crashed

A memorial garden has been created, partially overlooking the site of the rail crash

Concern over the increase led the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB) to write to Network Rail and all train and freight operating companies.

Mark Phillips, RSSB chief executive, said the 20th anniversary of the disaster was "a timely reminder of what can go wrong if we don't keep our eyes on the ball".

"We need to look at current train protection technology and industry initiatives, and ask whether enough is being done," he added.

Mr Duckworth said: "The risk is now that there hasn't been a serious rail crash for 20 years, standards might drop and focus might change.

"The industry needs to keep recognising that safety is of great importance, because though these incidents don't happen anymore, when they do occur they are devastating."

- Published5 October 2014