Instagram filters: 'Our skin is for life, not for likes'

- Published

'Our skin is for life, not for likes'

"Some Instagram filters make a mockery of my Asian features. I find them triggering because I was bullied about this exact thing as a child."

British-born Chinese vlogger Shu Lin uses Instagram as an everyday tool for her storytelling, and, like many, has used filters to retouch her posts in the past.

But the 28-year-old, who lives in north London, says she has recently noticed a more sinister side to the technology.

Filters, which began as cute puppy dog ears and love heart eyes, have now evolved into face, eye and skin colour-transforming toolkits for the everyday user.

Some Instagram filters have triggered bad feelings for Shu

One filter, which attempts to mimic Asian features, has particularly offended Shu.

She believes it perpetrates offensive stereotypes.

"I'm of Chinese heritage - and I spent a lot of my childhood being made fun of," she said.

"People would pull back their eyes and point out my high cheekbones and thick lips, so when I see filters called 'Asian Beauty' or 'Geisha' - which completely transforms the users face for, essentially, a trend - it hurts.

"Growing up, I had a lot of identity struggles, so when I came across the 'Asian Beauty' filter, I found it very offensive as it negatively reinforces all the stereotypes about Asian features.

"This filter triggered those bad feelings I had about myself when I was bullied about my features at school."

And she's not alone.

Vaani said the "choco skin" filter made her look unrealistically orange and not at all like her natural self

Vaani Kaur, a 29-year-old teacher and activist from Harrow, north-west London, discovered a filter titled "choco skin" on the platform.

She shared before-and-after images of herself using the filter to show its "outrageous" skin-darkening effect, calling it a form of "blackface".

She claims filters that darken skin are harmful to the self-esteem and mental health of BAME users.

"Our skin isn't an exotic look for selfies. People of colour don't have the privilege to be white when it might help us," she said.

"I can't, for example, turn my dark skin off to walk down a street in a potentially racist area.

"The choco skin filter is brownface - basically a form of blackface.

"People can't just wear us like an accessory and ignore all negative connotations to dark skin," she said.

"We are in our skin for life, not for likes."

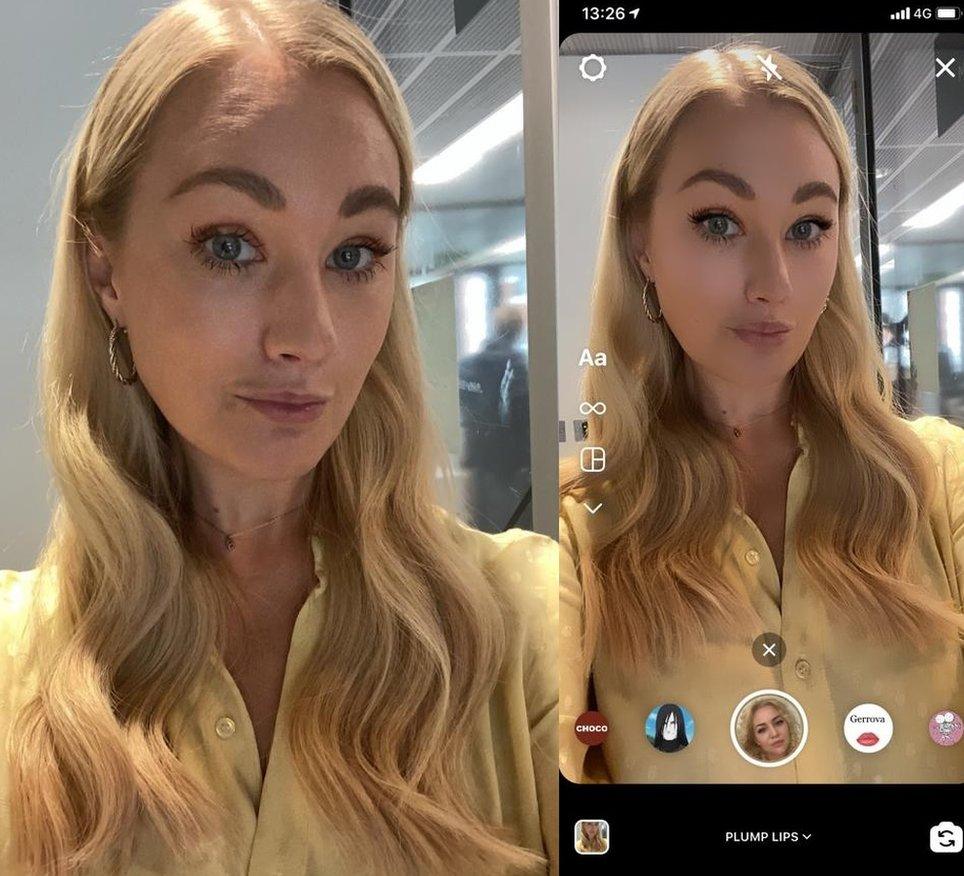

BBC reporter Sarah Lee using a lip-plumping filter that still exists on Instagram despite the platform's face-altering ban

Vaani sent a message to creator of the filter to raise her concerns, but was shocked by the response.

"She replied saying she didn't see any problem with it, that she preferred how she looked with a tan and that being dark was a virtue," Vaani explained.

The filter was eventually removed from the platform, but Vaani says hundreds of discriminatory filters, with similar names, still remain.

The BBC also contacted the creator of "choco skin" but did not receive a response.

'Systems aren't perfect'

Instagram, which is owned by Facebook, told the BBC that it does not ban effects simply for adding cultural or religious makeup or clothing, but it does ban effects that focus on harmful stereotypes linked to a protected characteristic.

It said it was investigating the effects brought to its attention by the BBC.

"We don't allow effects that focus on harmful stereotypes or directly promote cosmetic surgery," a Facebook company spokesperson said.

"We use a combination of human review and automated systems to review effects before they appear in the gallery.

"These systems aren't perfect, which is why we're constantly working to improve and we encourage anyone to report effects they think break our rules."

Instagram filters are created via Spark AR software, and range in complexity.

The social media company recently banned filters that depict or promote cosmetic surgery, amid concerns they harm people's mental health.

Effects that make people look like they have had lip injections, fillers or a facelift were also among those banned.

Despite this, at the time this article was written, the BBC found dozens of face and lip-altering filters still exist on the site.

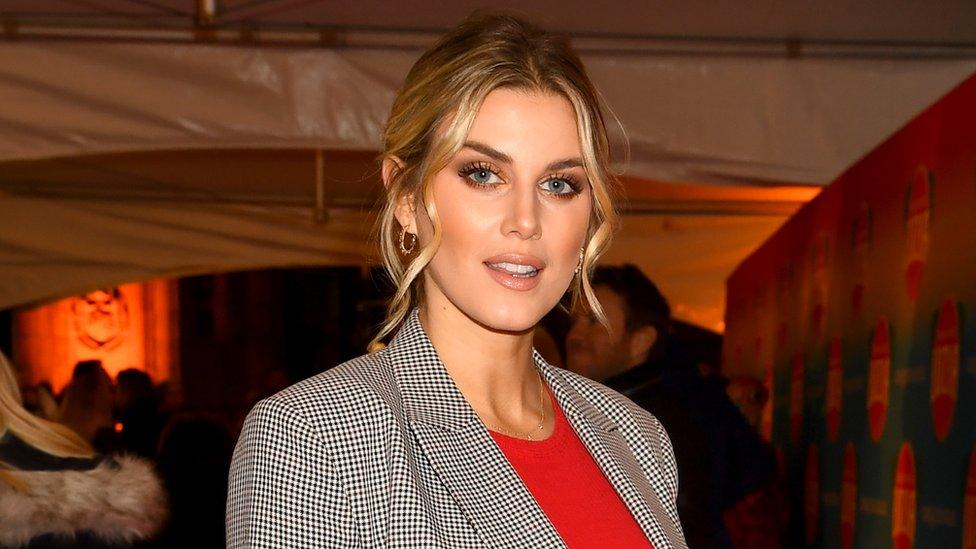

Former Made In Chelsea star Ashley James says Instagram filters are having a negative impact on girls and women

More needs to be done to help safeguard its users, according to body positive influencer and former Made in Chelsea star Ashley James.

"When filters first started they were just kind of cute and silly - like dog ears - it wasn't ever face-altering, and I know it's having a devastating impact on people's mental health," she said.

"Altering our appearance has become a commodity. We are almost being forced by these filters to change how we look offline to match the online version of ourselves.

"As for filters that change your ethnicity, I find that horrifying. Anything that is exaggerating different ethnicities is completely wrong and I believe all filters should be modified by Instagram."

Allow Instagram content?

This article contains content provided by Instagram. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read Meta’s Instagram cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The 30-year-old, who has gone "filterless" on social media, said Instagram should either remove filters altogether, or ensure edited photos are stated as such.

"Social media has a simple responsibility - it doesn't need to create filters that change your face shape, your skin colour or eyes."

But creative director Andrew Foxall said there should not be a uniform approach to monitoring filters.

Mr Foxall, who runs a design studio in Shoreditch, had his "Rhinoplasty" filter - which imitates the aftermath of a nose job - removed after Instagram's face-altering ban came into force last year.

American supermodel Bella Hadid (right) used Mr Foxall's Rhinoplasty filter

"I don't think Instagram should have removed our filter. It was uncalled for," he said.

"I've seen a lot worse out there and Instagram shouldn't have a one-size-fits-all approach to this.

"We must also take creative freedom into account when deciding what is wrong and right."

The filter has since been pushed "underground", forcing Mr Foxall's studio to send out secret links to those wanting to try it.

Liam Preston, head of the YMCA's Be Real campaign,, external said while he would never want to destroy creative freedom, social media could do more to safeguard younger people.

He believes filters that change a user's ethnicity reinforce racial stereotypes and legitimise cultural appropriation.

"By encouraging schoolchildren to mimic different ethnicities digitally it may lead to the normalisation of such practices away from their screens," he said.

"If they believe it is fine to do so online, why would they not perceive this to be OK in the real world?"

Vaani said people shouldn't be able to cherry pick the colour of their skin when racial discrimination is a very real problem

"Having a filter to darken yourself or change your ethnicity for a trend is not acceptable when racial and cultural discrimination are still very real problems," Vaani added.

"People shouldn't be able to just try us on for a bit of fun and Instagram needs to realise that."

Follow Sarah Lee on Twitter at @Sarahkatelee_, external

- Published22 July 2020

- Published2 September 2020

- Published23 October 2019

- Published7 September 2020