Why Transport for London's finances are far from healthy

- Published

- comments

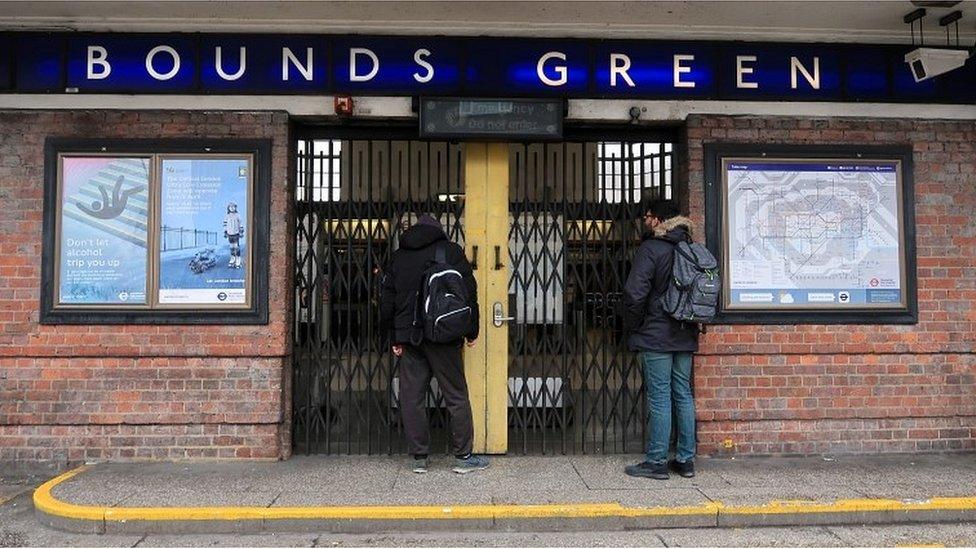

Transport for London has significantly reduced the number of Tube services because of coronavirus

Sadiq Khan has clashed with his mayoral predecessor Boris Johnson over claims made by the prime minister that Transport for London (TfL) was "effectively bankrupt" even before the Covid crisis. Mr Khan rejects this, and has called Mr Johnson a "liar". He insists he was balancing the books until the UK was crippled by the coronavirus pandemic. What is the bigger picture?

Let's start at the beginning, in 2000, when TfL was created. Over the past 20 years, TfL has been run by three mayors with differing ideas about how best to repair London's Tube network and to build for the future.

Both of those things cost money. Over the past two decades, TfL has received a mixture of government grants, fare income, sponsorship and huge investment loans from banks in order to keep the Underground on the move.

Sadiq Khan has accused the prime minister of lying about TfL's finances

Mr Johnson enjoyed two consecutive stints as mayor of London, between 2008 and 2016. A TfL report, external published a month before he left office showed TfL had a nominal £9.148bn of debt.

Three years later, about 12 months before coronavirus hit the UK, TfL published new accounts showing its nominal debt had increased to £11.175bn in real terms - stripping out the effect of rising prices or inflation.

What factors help to explain TfL's current financial state?

Crossrail - more money, more problems

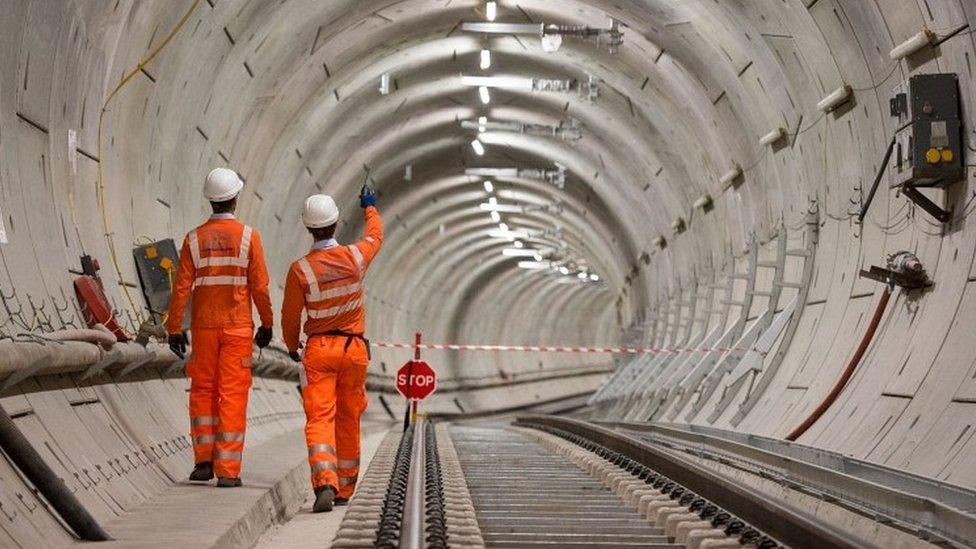

TfL's commissioner Andy Byford has been asked to review the latest Crossrail delays

TfL is dealing with financial pressures on several fronts - before coronavirus, arguably the biggest issue was the Crossrail project, which is overspent and late.

As sponsors of Crossrail, in October 2007 TfL and the Department for Transport (DfT) agreed funding of £15.9bn for the project., external

However, more money was needed and so in 2009, in his first term as mayor, Mr Johnson announced he had "secured one of the largest loans ever for a transport project" - an extra £1bn from his "good friends at the European Investment Bank", external for "the unstoppable force that is Crossrail".

Project Manager Andy Alder says he is proud of the first tunnel

Fast-forward to 2020 and there still is no Crossrail running through central London.

In fact, in August it was announced that the central section of Crossrail, between Paddington and Abbey Wood, is not expected to open until the first half of 2022 - a further delay to the line since the previous planned summer 2021 delivery date and well beyond the initial intended opening date of 2018.

The escalating costs of Crossrail are huge for TfL and the DfT and, at the same time, TfL has been denied a source of income from fares, commercial advertising and retail units at stations.

In 2018 TfL's then-transport commissioner Mike Brown said Crossrail's initial delay would cost TfL about £20m in fare revenues.

Add another four years of lost income and it is easy to see the drain Crossrail continues to have on the accounts.

Crossrail's original budget was set at £15.9bn in 2007 but cut to £14.8bn in 2010

But, it gets murkier.

Crossrail CEO Mark Wild also said in August, external: "Work is ongoing to finalise the cost estimates" - effectively the actual final construction cost of Crossrail is not known.

Even as Mr Johnson and Mr Khan were exchanging harsh words last week, investment service Moody downgraded TfL's long-term ratings to A1 from Aa3 and "changed the outlook to negative", external.

Essentially, the lower the rating the tougher it is to borrow money cheaply in the future.

Moody's said in a statement: "The downgrade to A1 from Aa3 reflects TfL's vulnerability to a weaker economic climate and the impact of the coronavirus pandemic, which will continue to depress fare revenues and other income over the medium term.

"The negative impact on TfL's budget has reversed its progress towards operational self-sufficiency, with TfL now reliant on continued support from the UK government."

Government grant down the tubes

George Osborne phased out the government's previously sizeable contribution to London's transport network

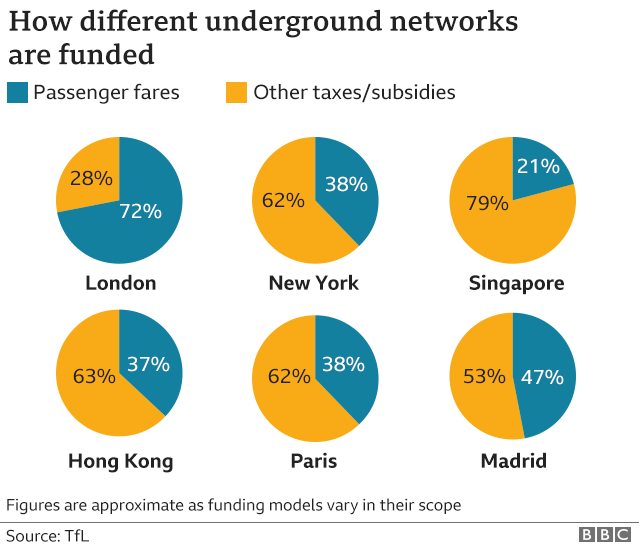

TfL documents show London, external is one of the only cities in the world that does not receive government funding to support the operating costs of its transport network - in comparison, fares on the Paris Metro make up only 38% of its income.

The UK's capital city used to get grants from the government, amounting to £700m a year.

This all changed in 2015 when Mr Johnson, as London mayor in the final full year of his term, and then-Chancellor George Osborne agreed to phase out this government operating grant.

A report in November 2018, external showed that TfL received only £55m in grants - a stark contrast to the help it received only a few years before.

It said: "The loss of the government operating grant within just a few years has been the single largest change to TfL's income streams. Just four years ago, TfL received £876m in grants."

Since then TfL has been heavily reliant on fares as a source of income.

Dwindling passenger numbers

People have again been encouraged to return to work from home, after being advised in the summer to travel into the office where possible

In order for fare income to flourish, TfL needs passengers; over the years, the number of people using the Tube has always been expected to rise.

This is especially the case when you consider London's population in 2000 was 7.5m, compared with 9.1m now.

However, in the past two decades, people's habits have changed.

In 2017, a year after Mr Khan took office, there was a 5% drop in rail journeys in London and 13m fewer Tube journeys were made compared with the previous year.

Passenger numbers on the Tube had been increasing since 2018 - until the coronavirus pandemic hit

It turns out bus travel activity in London reached its peak in 2014, external, and has been struggling ever since.

A City Hall source told the BBC "there are a lots of reasons" for this.

"It seems the big reason is the decline in bus travel for leisure and non-work reasons. Less people are getting on a bus to go shopping."

If this does help to explain falling numbers of bus passengers, there was no such impact on Tube travel after 2017 - it had been increasing since 2018 until the middle of March of this year.

Crippling cost of coronavirus

In 2019-20 Transport for London earned £4.9bn from fares - 47% of its income

TfL has just come through the most challenging financial quarter in its 20-year history.

Bosses recently said the coronavirus pandemic had caused a "catastrophic impact" on the business. The most damaging consequence has been the calamitous drop in fare revenues.

In March, passengers were urged not to travel unless absolutely necessary and 40 Tube stations across London were closed in order to deal with staff absences.

Since the pandemic, TfL's fare revenues have fallen by 90%. There has been the same drop in advertising revenues, as companies cancelled contracts to advertise on the London Underground network.

Significant health and safety changes to projects such as Crossrail and the Northern Line extension to Battersea also cost money.

In March, TfL reported up to a third of its workers were off ill or were having to self-isolate

In May, TfL bosses and the mayor had to come to an agreement with the government over a £1.6bn bailout deal to keep London moving.

The deal came with the imposition of strict conditions on the London transport network, such as the congestion charge rising from £11.50 to £15 and being enforced every day from 07:00-22:00, and the removal of free travel cards for children.

About 800 sanitiser units have been put up across the London Underground network to help reduce the spread of coronavirus

As lockdown measures eased, cleaning regimes across the Tube network were ramped up, also at a cost. Passenger numbers slowly rose during the summer months - but to nowhere near the level before the pandemic.

Figures from 8 September show 700,000 people used the Tube before 10:00 BST - which was up 10% on the previous week but represented only 32% of the number of passengers on the Tube before the March lockdown.

Now Londoners and commuters into the capital are again being urged to work from home, TfL commissioner Andy Byford admitted earlier this month that its finances were "right on the wire".

Last month Boris Johnson announced a range of new restrictions to combat the rise in coronavirus cases in London

Last week, the government said it would continue to abide by the terms of the £1.6bn bailout package until 31 October - an extra fortnight on the deal representing a sum roughly equivalent to £113m - but stricter conditions are being demanded by the government, as TfL seeks a £3bn package to last throughout 2021.

Prof Tony Travers, of the London School of Economics, said bankruptcy was "never quite the right word" when describing TfL's finances.

"By law TfL is required to balance the books year on year," he added.

"It can borrow for capital projects but it cannot borrow for day-to-day spending. If it can't [balance the books] then by law it has to file a Section 114 order (the equivalent of a public company bankruptcy) that bans expenditure and would lead to mass redundancies and services stopping.

"TfL's operating costs are about £6bn a year and its fare income is [usually] about £5bn. It would be amazing if it could get around £2bn this year, which means TfL is going to be £3bn down."

Fares freeze

Fares are due to increase in 2021 for the first time in years

Much has been made about Mr Khan's flagship policy of freezing fares across the London Underground network for the duration of his four, now five-year, tenure as mayor (the term was extended due to the 2020 mayoral elections being postponed amid the coronavirus crisis).

Although controversial at the time, the fares freeze has been fully paid for through TfL's efficiencies programme, outlined in its December 2016 Business Plan, according to City Hall.

In 2018, then-TfL commissioner Mike Brown, said the mayor's TfL fare freeze had helped address the decline in passenger numbers overall.

Currently passengers face fines for not wearing a face covering on the London Underground network

The total forgone revenue of the fares freeze over the past four years is estimated to amount to £640m - the equivalent to roughly a year's worth of the government grant that was axed a few years ago.

Nevertheless, after four years of frozen prices, Tube and bus fares are set to increase in 2021 after Mr Khan said this policy would come to an end.

How expensive these new fares will be is still very much up for negotiation between the government and the mayor.

For Caroline Pidgeon, the deputy chair of the London Assembly's Transport Committee, Mr Johnson and Mr Khan need to stop squabbling over who has done what.

The Liberal Democrat assembly member said: "No-one is to blame for the devastating impact of Covid on TfL's day-to-day finances, and petty party politics about meeting the gap in funding is helping no-one.

"However, the real elephant in the room is the true cost to Londoners from the huge delays in the opening of Crossrail, which have pushed TfL's long-term borrowing to new heights."

Prof Travers's simple observation is that coronavirus has clearly been detrimental to TfL's financial situation.

"By far the biggest impact on TfL's finances is the loss of passenger income, which has been a direct response to government lockdown or the three tier policies.

"Against that backdrop of that scale, it is not something the mayor could have done anything about."

- Published21 August 2020

- Published8 September 2020

- Published14 May 2020

- Published18 November 2016