Gay Ugandan asylum seekers 'in danger if sent home'

- Published

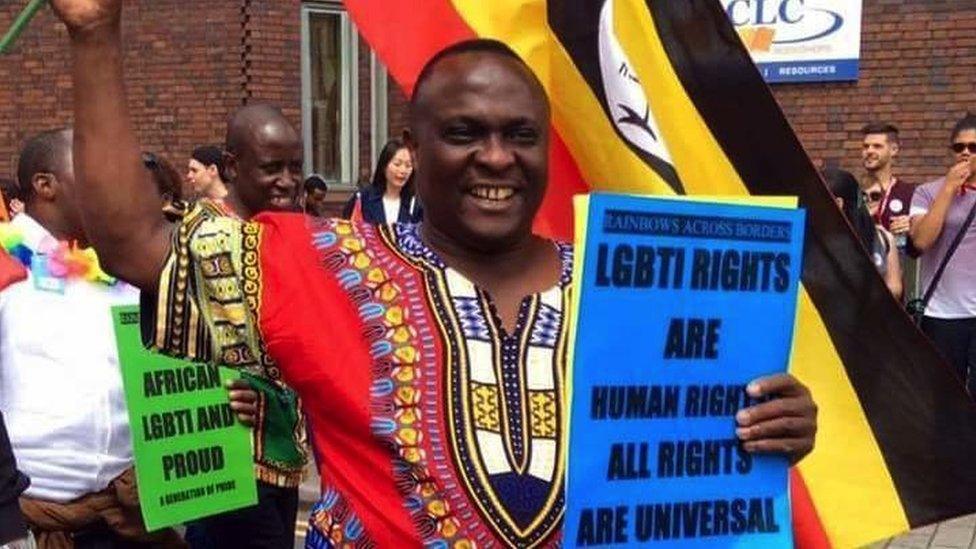

Godfrey, pictured here at a protest in the UK, says he watched a friend shot dead for being gay

Same-sex liaisons are illegal in Uganda. People convicted of homosexual acts can be sent to jail for the rest of their lives. Some gay Ugandans survive by staying under the radar and live a shadowy half-life, presenting a straight face to the world. Others manage to leave their homeland, seeking asylum where they won't be persecuted for being who they are.

Because Godfrey is both gay and Ugandan, he says he was expelled from school, rejected by his family and sacked from his job.

Because Yudaya is both gay and Ugandan, she says she cannot contact her family and is being sought by police.

Because Rodney is both gay and Ugandan, he says he was forced to live on the streets and used to carry poison in his pocket in case he needed to kill himself before getting arrested again.

Rodney, Godfrey and Yudaya are now in the UK and have applied for asylum.

None has succeeded.

These are their stories.

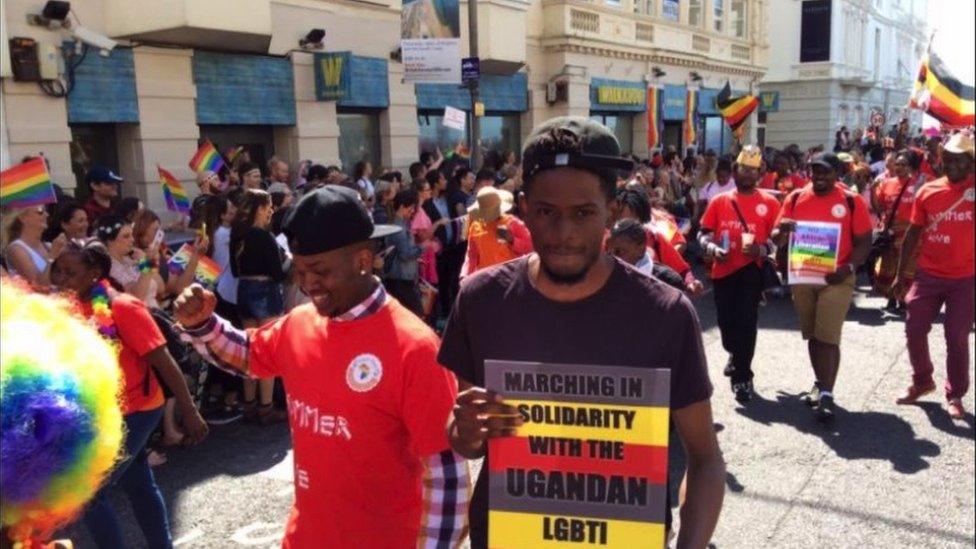

Rodney could not believe how different attitudes to homosexuality were in London compared to Kampala

Rodney, who is now 23, was reported to his school because he was seen cuddling a boy. When he got home, his family beat him up.

About two weeks later, under cover of darkness, he says he was woken by bright lights and taken away by six men who hit him and crushed his throat with a crowbar. The men, one of whom was a community leader, slapped him and interrogated him.

They rubbed something on his lips, something that burned and hurt and caused a scar he still bears.

He was 15.

He was kept in a house for two weeks with other boys - some he recognised from his neighbourhood or football team - who were in the same kind of trouble. Some of them had been tortured, Rodney believes.

"Some of the boys there, they had no fingernails. They had been pulled off. [Their captors] would call us one by one. Most of the time the person called would not come back. One time my friend Ruby was called. They brought him back dead."

After various misadventures, Rodney managed to get away and lived on the streets of Kampala. Eventually a woman took him in.

Rodney is staying with a relative until he finds out what the Home Office decides

Rodney says he was expected to cook and clean and shop for the woman in her one-room rental home. He hated himself, he says. He bought himself some poison and kept it in his pocket, doing his best depending on how he was feeling, to either ignore or obey his internal voice telling him to drink it.

Eventually he went back to his family, who had believed he was dead. His father told him to leave or he'd kill him, but an aunt pointed out that Rodney was clever and had done well at school. She also said she could "cure" him, could "turn him back".

Rodney did well enough in exams to get into a British university. Arriving in Portsmouth, the 18-year-old couldn't believe his eyes.

"It was a different world. Life was different, it was good. You could go to a club and all the gay people would be there. I met another Ugandan man and he took me to Pride in 2017.

"I was like, 'oh my God'. I took so many pictures. But I put them on Facebook and my cousin saw them.

"Then I was called into college and was told my tuition fees had not been paid. I tried to call my father and my phone had been cut off. I checked my email and I had a message from him. It said that from now on I am dead to them. That was in 2017 and it was the last time I heard from them."

Africa and homosexuality laws

Laws outlawing same-sex relations exist in 31 out of 54 African countries, according to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association, external (ILGA).

Gay sex can be punishable by death in northern Nigeria, Sudan, Somalia and Mauritania.

Same-sex liaisons are illegal in Uganda. People convicted of homosexuality can be sent to jail for the rest of their lives.

However, Angola, Mozambique and the Seychelles have all scrapped anti-homosexuality laws in recent years.

The chaplain at Rodney's college put him in touch with the Citizen's Advice Bureau, which told him about the asylum process.

Rodney was interviewed and asked about his relationships. He told them that he had never been in a serious one. His application for asylum was turned down. He says he was told it was because he was not in a same-sex relationship, and his nature was quiet rather than flamboyant.

"Basically they were saying I was not outgoing or camp enough. That I could go back and behave in a discreet manner.

"I had been hiding for a lifetime, I came to a country where I can go out and be myself. Now I'm just waiting to see if I really have to go back and hide again."

Godfrey says he saw his friend shot for being gay

In 2002, after being discovered in a same-sex act, 18-year-old Godfrey went on the run with a friend. Armed men found them and attacked them. Godfrey hid in the latrine, and stayed there as he saw his companion tortured and murdered.

"They came with guns and surrounded the house. They grabbed the shotgun and shot him in the side of the head when he was kneeling down. I thought they were coming to the latrine to take me.

"What is next for me? I am so scared, the police are looking for me and I've already committed the gay sex," he said.

Godfrey and his friend had already fled the capital, Kampala, and were in the rebel-held territories of northern Uganda. He was unpopular with the authorities, he says, not just because he was gay, but because he'd spoken out against the president, Yoweri Museveni.

"I was dismissed from school. When I was dismissed from school I was rejected by my family. My father said 'there is no way I can keep you here, because already the school has informed the police'".

After his friend was murdered, Godfrey managed to get to Kenya and from there he was smuggled to England.

Nine years later he applied for political asylum. He was refused.

He then applied on the grounds of his sexual orientation. Again, he was refused. He has appealed and is waiting for the Home Office's decision.

Godfrey said the screening and interviews involved in the process made him anxious because he felt his questioners did not believe he was gay.

"There's no way I can prove it," he said.

"I mean, do you want me to find a man and kiss him? Would that do it?"

Yudaya said her family no longer want to speak to her

Yudaya has been studying in the UK since 2018. She was not openly gay back home but she did have a girlfriend, who is still in Uganda.

Her family recently found out she is a lesbian.

"My big sister called me. She said the police came, and to please not contact my family again.

"She said: 'We asked why the police were looking for you and they explained you are a lesbian. You are with people spreading homosexuality around.'"

Yudaya said the Home Office, although it accepted she was gay, was not convinced she would be in danger if she had to go back to Uganda.

"To them, if I lived my life quietly, if I concealed my sexuality before, then it's possible i can go back and live in another area [of the country] and conceal my sexuality again, but I don't think that's the case any more".

The Home Office said:

"The UK has a proud record of providing protection for asylum seekers, and the Home Office recognises that discussing persecution may often be distressing, which is why our caseworkers receive extensive training, and also work closely with a range of organisations specialising in asylum and human rights protection which can provide support for LGBT+ asylum seekers during the asylum process.

"However, the Home Office rightly expect individuals to be able to satisfy us that they are at a genuine risk of persecution in order to be granted asylum, which has to be obtained through oral testimony at interview."

Leila Zadeh, executive director of the UK Lesbian and Gay Immigration Group, external, said that refugees were often disbelieved by officials who then asked inappropriate and demeaning questions.

"The interview is particularly hard, because they have to try to prove something which is virtually impossible to prove, which is your sexual orientation, gender identity, gender expression or sex characteristics.

"We are working with people who've been through a really traumatic past, very often fleeing persecution or fear of harm by members of their own family.

"When they get to the UK and they enter the asylum system it's quite sad if they don't feel supported, but rather they feel like they're going through even more trauma and even more stress, which is the last thing that people who need our care and protection should have to experience."

Ugandan ethics minister Simon Lokodo wants the death penalty to apply to those caught in same-sex acts

If Godfrey, Yudaya or Rodney are forced to return to Uganda, they face deeply entrenched and violent prejudice like that of the country's minister of state for ethics and integrity, external, Simon Lokodo.

A former Catholic minister who believes the current penal law is "limited" and wants same-sex acts to be punishable by death, he has described [heterosexual] child rape as "preferable to homosexuality".

He claims "homosexuality is not natural to Ugandans" and a "massive recruitment by gay people" took place in schools, promoting a "falsehood that people are born like that".

"The current law only criminalises the act. We want it made clear that anyone who is even involved in promotion and recruitment has to be criminalised. Those that do grave acts will be given the death sentence," the politician said.

Godfrey, who 19 years ago says he watched his friend being shot through the head, is terrified of having to go back to Uganda. The UK, he says, is his "safe haven".

Yudaya's family can offer no support or protection. If she returns she will be alone and forced to live a lie.

And Rodney might finally be driven to use that poison he kept in his pocket.

Related topics

- Published21 June 2012

- Published18 February 2019

- Published25 February 2014