London bus drivers: 'Unanswered questions' over Covid deaths

- Published

- comments

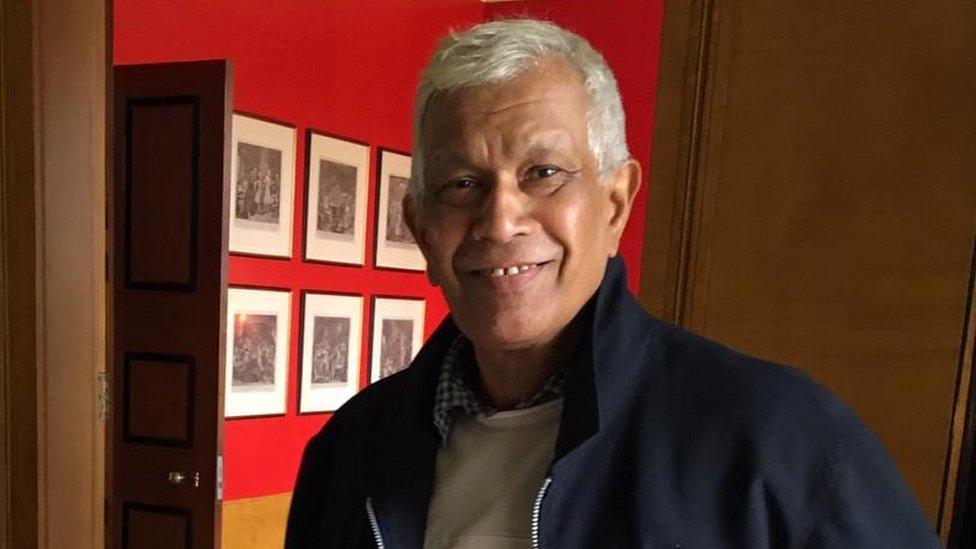

Leshie Chandrapala said her father was "incredibly proud" to be a bus driver

Leshie Chandrapala lost her father Ranjith nearly a year ago and the past 12 months have been incredibly hard.

He was 64 when he died on 3 May, having been a driver on the 92 bus route which serves Ealing Hospital.

It was a job he loved doing, but when the pandemic began last March year, he was not given any personal protective equipment (PPE).

Leshie wants a public inquiry into bus driver deaths to find out why even basic safety precautions took so long to introduce.

"It's incredibly raw," she said. "The more I read about measures that were or weren't taken, I just have so many questions that have been left unanswered.

"I don't think Sadiq Khan's report dug deep enough because to my mind safety measures that were asked to be put in place weren't brought in soon enough at the bus companies, especially my dad's bus company."

As of 15 March 2021, the number of bus worker deaths in London is 65. Fifty-one of them were drivers.

Ranjith Chandrapala was a driver on the 92 bus in Ealing

"Bus drivers were told they didn't need PPE at the start [of the pandemic] and we need to know why that was, why lives like my dad's weren't thought valuable enough," said Leshie.

"I think dad could be still with us if he had been given the proper PPE and the cabs had been secured properly, and had the public been boarding from the back and had lockdown happened earlier."

Bus drivers are not included in the assurance scheme that pays £60,000 to families of health and social care workers, external if they die.

A preliminary report published in July, external by the Institute of Health Equality at University College London - which was commissioned by City Hall - made difficult reading for many families, who felt it was blaming the victims.

It showed that between March and May 2020, the mortality rate in male bus drivers was 3.5 times higher than men of the same age in other occupations.

The report highlighted underlying health conditions as possibly being a contributory factor.

It found that: "Additional risks of Covid-19 related mortality for bus drivers include: age, living in areas characterised by deprivation, having a high proportion of members of black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) groups; and the presence of underlying health conditions - hypertension, cardiovascular disease and diabetes - which are associated with increased likelihood that infection with Covid-19 becomes fatal."

But many families do not recognise those health conditions among those who died.

The report also highlighted how different bus operators implemented measures, such as rear-entrance boarding for passengers and cab screens, at different times.

There are 10 privately run bus companies operating services in London and, according to the report, several were "slower in initiating some of the actions recommended and there was inconsistent action and advice".

Measures introduced to protect bus drivers included stopping passengers boarding through the front doors

The first lockdown in England began on 23 March, but there were then weeks of campaigning by unions and bus drivers, as well as media coverage of the issue, before protections were introduced.

Mr Chandrapala's company introduced middle-door boarding on 19 April and he was also given hand sanitiser - but there were no masks. He first showed symptoms of Covid five days later.

His daughter wants to know "why there was such a lag between the Department of Transport asking for these measures to be put into place and them actually being put into place".

She said: "I know that with my dad's bus company, the public were still front boarding as late as 18 April. That's a huge time period where these measures could have been implemented quickly."

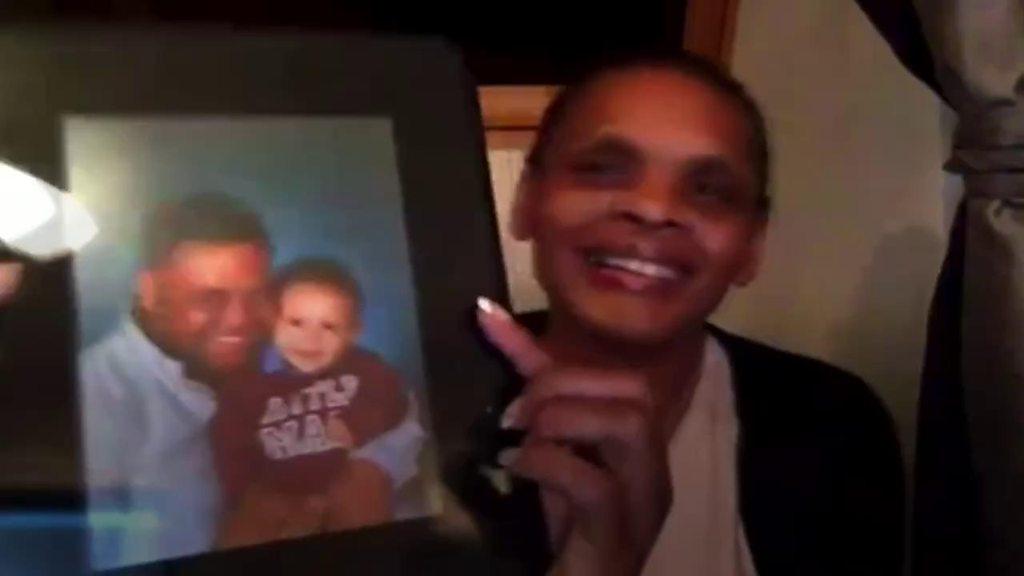

Anne Nyack said her son was not given adequate protective gear in his work as a London bus driver

The UCL report concluded that many of the protections were introduced too late and "after most of the drivers who died had become infected".

The report added: "There is scope for Transport for London (TfL) to develop clear guidance on rapid and simultaneous implementation of measures in the event of spikes of infection in London or increased infection rates among staff."

But has that happened?

There are those who think the problems are much wider and driver deaths are the result of systemic failure.

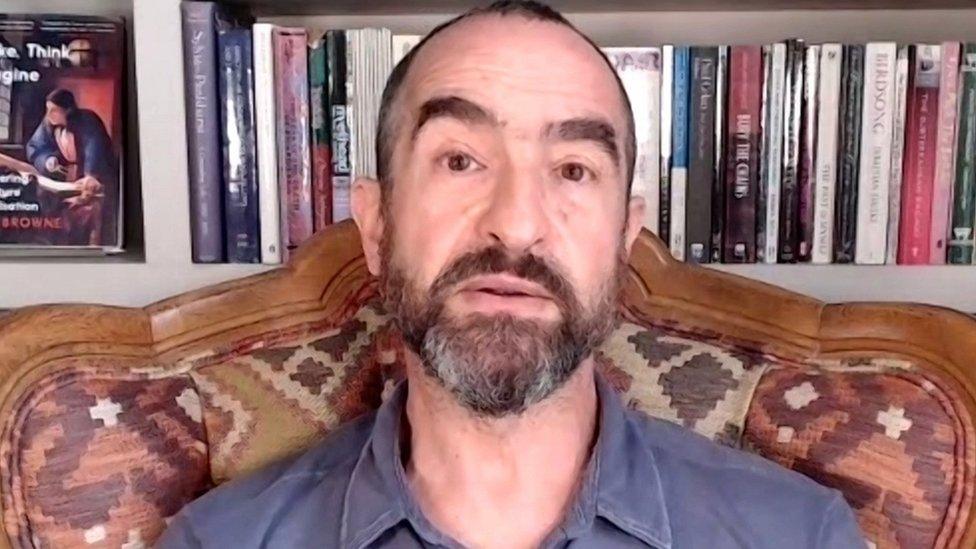

Michael Liebriech said he was not surprised to see very high death rates among London bus drivers

Michael Liebriech was on the TfL board from 2012-18 and was deputy chair on the safety panel.

"Tragically, it has been no surprise to me to see these very high death rates among London bus drivers because the system is simply not in place to ensure their health and safety," he said.

"The safety management system is designed to push responsibility down to the bus companies and not to oversee it in a meaningful and robust way by TfL.

"For an example, we know that they don't even hold copies of the risk assessments for bus drivers by the bus companies."

That is something Mr Liebriech considers "really quite extraordinary".

He added: "They haven't put into place a robust safety system that I would recognise from other industries - energy, manufacturing, airlines, train industry - they simply don't do that and, tragically, we've seen now these consequences."

Up to 15 March 2021, the number of bus workers who have died with Covid is 65

TfL has said the "initial different phasing [by different operators] was due partly to the emerging information around what the most effective interventions were, learning how to best implement those interventions, along with the availability of materials to implement them across all garages.

"The regular meetings between the operators and TfL have enabled us to ensure everyone is aware of emerging changes, share information and agree implementation."

Chief health, safety and environment officer Lilli Matson added that both "TfL and the bus companies have followed PHE advice as it has evolved" and would "continue to do everything that is humanly possible to protect bus drivers".

Over the past year, I have spoken to bus drivers who think miles are put ahead of lives.

They complain about unclean facilities and how hard it is to remain socially distant in their depots.

Leshie Chandrapala's father, like many other key workers, was keen to help London as Covid hit.

She believes the families of drivers who died "deserve answers" and has vowed to fight on to get them.

"He signed up to be a bus driver, he was incredibly proud to be one, to help the city during the pandemic and do his bit, but he did not sign up to give his life."

- Published11 January 2021

- Published27 July 2020

- Published15 June 2020

- Published6 April 2020

- Published17 April 2020

- Published7 April 2020

- Published13 April 2020