Tate Modern attack: Jonty Bravery had history of violence, report finds

- Published

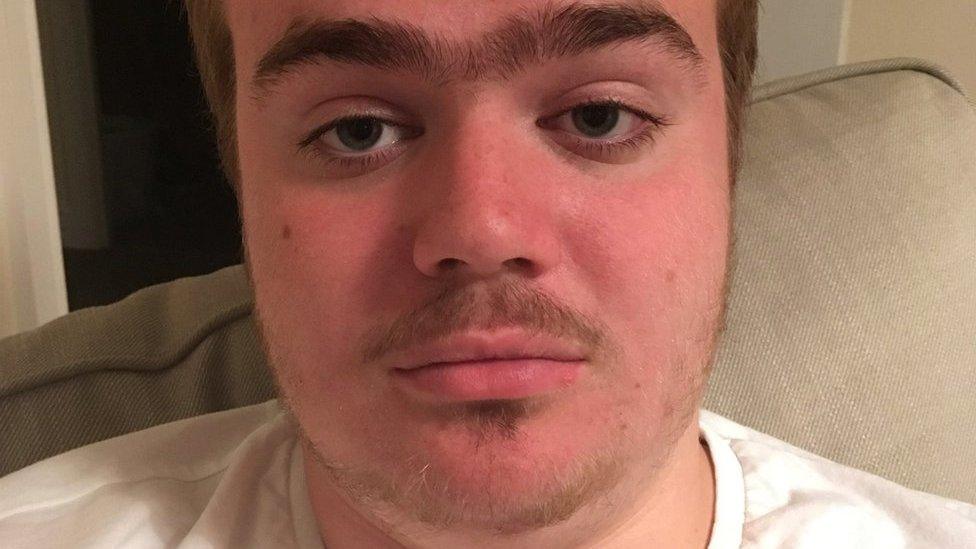

Jonty Bravery, now 19, was 17 years old when he was charged with attempted murder

A teenager who threw a six-year-old from the 10th floor of the Tate Modern had a history of violent behaviour.

A serious case review found that Jonty Bravery had expressed a desire to hurt people prior to the attack in 2019.

The review blamed an undiagnosed personality disorder for the offence, and found professionals failed to distinguish "callous" traits from behaviours linked to Bravery's autism.

It called for "critical lessons" to be translated into action.

It highlighted a series of troubling incidents involving Bravery in the two years before the attack, including threatening to kill members of the public and putting faeces in his mother's make-up brushes.

But his violent behaviour had been less frequent in the period before the Tate Modern attack, while he was living in a placement with two-to-one care funded by Hammersmith and Fulham Borough Council and the NHS clinical commissioning group (CCG).

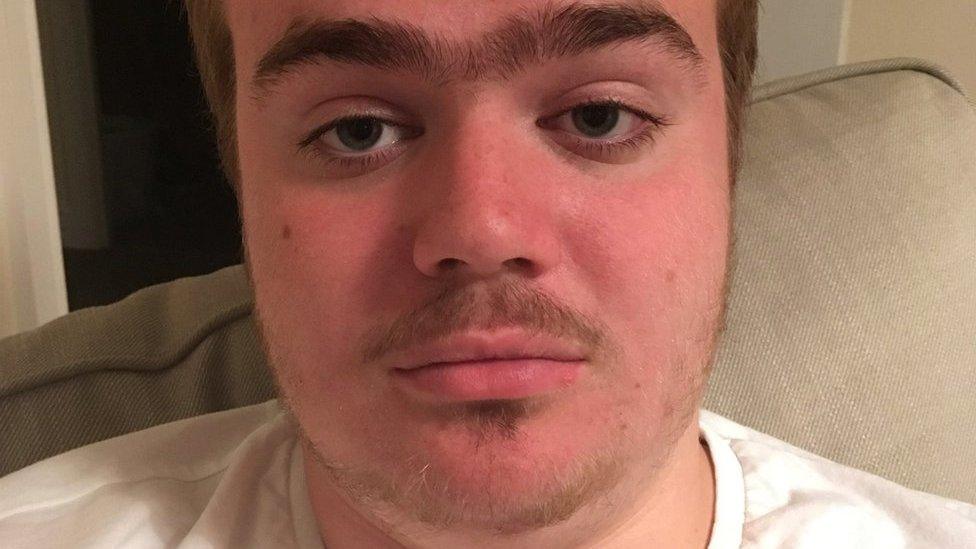

The six-year-old boy was taken by air ambulance to the Royal London Hospital

The report says: "There was no recent evidence that he presented a risk to other children or adults unknown to him.

"It was in this context that he was progressively given more freedoms, which saw him able to visit central London unaccompanied on the day of the incident."

On 4 August 2019, Bravery made his way to the Tate Modern's viewing balcony where CCTV footage showed him following young children and looking over railings.

He then threw the six-year-old from the viewing platform and he fell 100ft (30m), suffering a bleed to the brain, and other injuries, including fractures to his spine.

Bravery, who was diagnosed with autism at the age of five, was jailed for 15 years in June for attempted murder.

The review, by the Local Safeguarding Children Partnership (LSCP), highlights a national shortage of specialist and residential community care for children and young people with complex and high-risk behaviours.

Bravery spent various periods of time being moved from psychiatric intensive care units, specialist residential schools and hotels from the age of 15 as his behaviour became more troubling.

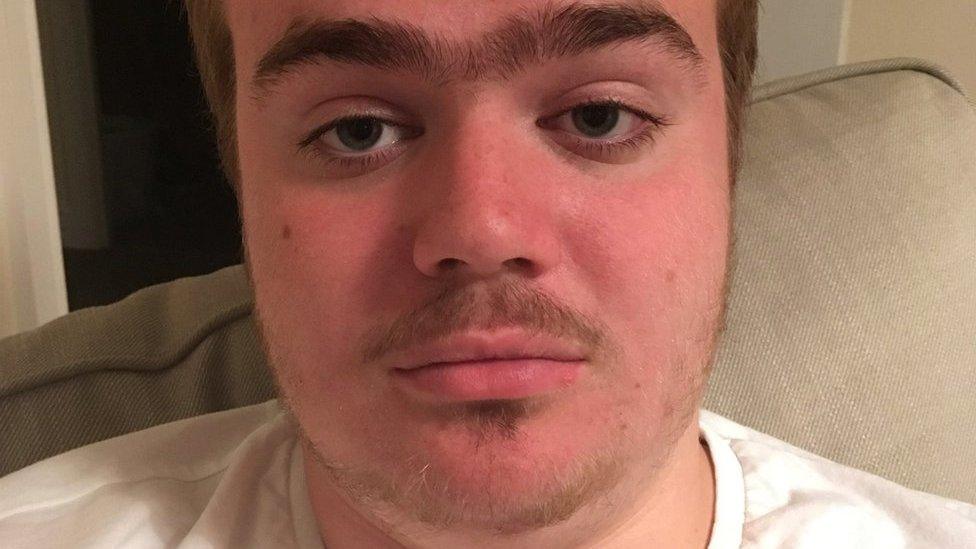

Bravery told mental health professionals that he was planning to kill his stepmother and sister

His parents thought this detrimental to his mental health, the report says.

His father told the review he felt "frustrated" at the apparent lack of expertise among private care providers dealing with his son.

Analysis

BBC special correspondent Lucy Manning

The key question: how was Jonty Bravery, with a history of violence, who had warned he would do something similar, allowed out alone to the Tate?

Today's report only adds to the disbelief that he was allowed to visit the gallery unaccompanied.

The report says there was no "recent" evidence that he posed a risk to other children or adults he didn't know.

Yet in the two and a half years before the attack at the Tate, Bravery was involved in at least eight assaults.

He attacked and bit another child, he attacked a support worker with a brick, he dragged a care worker by her hair, he assaulted police not once but three times, he confessed he had thoughts about killing himself and others, he punched a member of staff in a restaurant and racially abused his care worker.

The last attack was just four months before he threw the young French boy from the Tate.

No-one is blamed for letting Bravery out although the system is criticised for the lack of treatment and residential places for him.

Last year, the BBC revealed a recording from 2018 where Bravery told some of his care workers he planned to push someone off a building and go to jail.

The serious case review accepts the care agency's statement that it had no prior knowledge of this and says the review didn't identify anything to undermine that.

It's unlikely this will provide much comfort to the injured boy's family as he relearns how to walk and speak.

During a four-week placement in a children's home in 2017, Bravery hit a climbing wall instructor at a leisure centre, deliberately damaged a car and assaulted a member of staff with a brick.

Later that year, he dragged a member of staff along the floor by her hair and, in 2018, he disclosed he was planning to kill his stepmother and sister.

The review says: "It is evident that professionals working with (Bravery) at this time did not think he would act on these statements, which were seen as attention-seeking behaviour.

"This was because all of (Bravery's) actions were viewed as products of his autistic behaviour and there was no consideration of these threats in a context of conduct disorder."

The boy had been visiting London from France with his parents

A psychiatric report in 2018 said Bravery, who is now 19, had learnt to use his autism as an excuse to evade responsibility for dangerous behaviour.

The review says Bravery needed residential therapeutic solutions that could enable him, as an autistic young person, to engage in a treatment regime for his conduct disorder.

"But such a residential option did not exist," it adds.

The LCSP says it is continuing to make improvements across police, health and social care in the delivery and co-ordination of support for autistic children and those with complex high-risk behaviours.

- Published22 December 2020

- Published9 December 2020

- Published25 June 2020

- Published7 February 2020

- Published4 August 2019

- Published6 December 2019