London's callings: Odd, obsolete and old jobs in the capital

- Published

Headwear of choice: a halibut

The parameters of the workplace are always in flux. One day a job has merit and meaning; the following day a supermarket cashier might be surplus to the robot army which has taken over the tills. An automated voice can remind a passenger to mind the gap just as well - and more economically - as a platform inspector.

Some professions look almost the same today as they did in the past - publicans still serve drinks, ironmongers continue to sell hardware and hairdressers carry on crimping.

Others are obsolete: employment-seeking official deathsmen (executioners) are out of demand; opportunities for dripping men (who collected and dealt in meat fat) are nowadays somewhat limited; and opium sellers, also mentioned on the census, are understandably reluctant to poke their head above the parapet (lest the Peelers spot them).

But what about badgy fiddlers, bummarees, or nob-thatchers? Cullet pickers and perruquiers? It may sound like they have disappeared from the Big Smoke - but have they?

Here are some of the capital's oldest, oddest jobs.

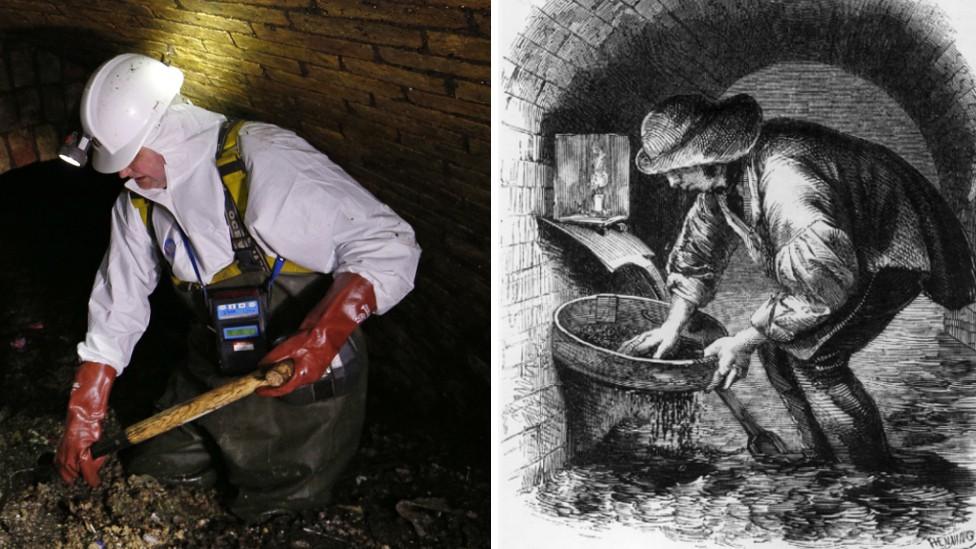

Tosher

It appears that "greasy velveteen" is no longer de rigueur in subterranean circles

A tosher was a person who scavenged in the sewers for valuables, "tosh" being a word for copper. Journalist-cum-sociologist Henry Mayhew's four-volume London Labour and the London Poor, external observed and interviewed a number of men who worked in "that subterranean city of sewerage".

They wore "long greasy velveteen coats, furnished with pockets of vast capacity, and their nether limbs are encased in dirty canvas trousers", Mayhew noted.

The toshers, Mayhew added, "appear to have a fixed belief that the odour of the sewers contribute to their general health". One of his interviewees described the smell as "roughish but not as bad as you might think", but there were places "where they tell me the foul air will cause instant death".

Somewhat unnecessarily, he added: "I never met with anything of that kind".

He was, however, less stoic about the rats: "I often see as many as a hundred at once, and they're whoppers in the sewers, I can tell you. Them there water rats, too, is far more ferociouser than any other rats. Do you recollect hearing of the man found in the sewers about twelve years ago? The rats ate every bit of him, and left nothing but his bones."

Today's equivalent might be a sewer worker - but rather than scrabbling through effluvia for scrap metal they go underground for maintenance, such as the grim job of clearing fatbergs.

Mayhew calculated that toshers would make in the region of £2 a week (the equivalent today of about £170). Today, degree apprentices with current water companies earn just over double that - and death by ferocious rat is less of a hazard.

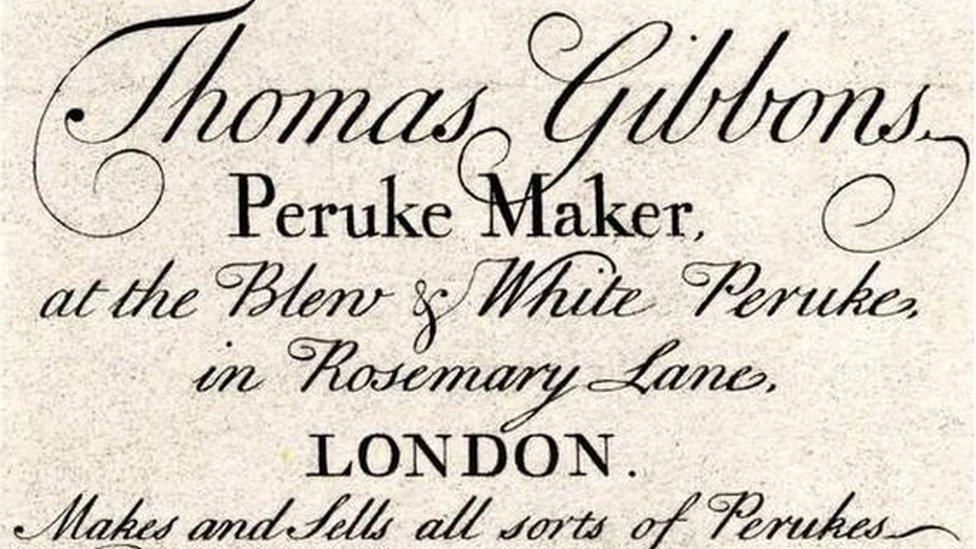

Nob-thatcher

It may sound like a fairly coarse insult to be bandied about after a couple of ciders, but a nob-thatcher was someone who made perukes, or men's wigs. A peruke was made of long hair, often with curls on the sides, and was sometimes drawn back on the nape of the neck.

The perruquier used goat, yak, horse or human hair and wove and knotted individual strands around threads, which were then attached, in rows, to a base of netting. The final stages included curling, dying, powdering, and pomades.

An individually tailored wig by a good maker was a signal of wealth and social rank and could cost the equivalent of thousands of pounds today.

The preface to Memoirs of an Old Wig, external claims that "in 1700, a young country girl got sixty pounds for her head of hair, and the grey locks of an old woman, after death, sold for fifty pounds". The Bank of England's inflation calculator translates that £60 in 1770 into more than £12,000 in 2020.

The wig and hairpiece trade is still strong today - according to industry figures, the UK female hairpiece, wig, and extension market, valued at £460m in 2019, is expected to reach nearly £900m by 2027.

Cullet picker

Glass is made by melting a mixture of various inorganic substances and cooling the melt under controlled conditions. Cullet, added to the original mixture at the beginning of the process, lowers the melting temperature

Cullet-pickers were another type of scavenger - this time of used glass. It could be sold to glassmakers who would use it in their furnaces to make a new batch - the addition of cullet makes the melting temperature lower.

It is a form of recycling still going strong. The Port of Tilbury, London's major port, is the starting point for trains carrying up to 1,200 tonnes of raw glass cullet travelling to Cheshire, where it is turned into new bottles and containers.

The cullet is made from glass from kerbside collections and bottle banks, which is processed in a recycling hub at the port.

The census

Since the first census of the UK there has been some attempt to catalogue occupations - in 1801 there was a broad classification of the fields of work: manufacturing, agriculture or neither.

Later 19th Century censuses simply asked for "Rank, Profession or Occupation", without any distinction between personal occupation or industry of employment.

It was not until 1851 that a comprehensive system, of 17 orders broken down into 19 sub-orders, of occupations was devised. The most common London jobs that year were in manufacturing (373,000 people) and domestic service (250,000).

The most uncommon job? The Queen (one person). Queen Victoria described her occupation as The Queen in the 1851, external census. Despite her status, it was Albert who was listed as the head of household. A decade later, though, this was addressed and Albert was relegated to the title of "husband".

Bummaree

Described by journalist James Greenwood in 1875 as "great burly fellows with bluff faces, deep chests, and still deeper voices, with a smack of the waterman about them... and a faculty for mental arithmetic which is perfectly surprising", a bummaree was a middleman between the large salesman and the retailer at Billingsgate fish market.

They would buy in bulk from the auctioneer and portion his purchase into convenient parcels to sell on to fishmongers.

Greenwood, known for his humorous social commentary, said of bummarees: "They may be classed under three heads : Rough, rougher, roughest.

"There is the swell bummaree, whom you can hardly tell from the auctioneer (the aristocrat of the market), and who 'bids out' freely for the choicest consignment of turbot and the highest-priced parcels of Tweed and Severn salmon, knowing that he will make his money out of West-End fishmongers, who must buy the pick of the market, no matter what the price may be."

The lowest on the scale were the costers who bought a single lot from the auctioneer and sorted it into quantities "he knows will suit the twopenny-halfpenny customers who are all he can hope for".

"These casual Bummarees are principally found about the pillars supporting the water-front of the market, and are objects of the special vigilance of the market constable, who often finds it a matter of some difficulty to extract from them the market fee of sixpence".

Later, the term was - and still is - used for the same role at Smithfield meat market.

Loblolly boys

Loblolly was a thick oatmeal fed to unwell people on board a warship. A loblolly boy, therefore, was the surgeon's assistant who did the feeding.

Other duties, more onerous than doling out oatmeal, included pouring tar into open wounds for healing, cleaning bed pans and clearing up vomit.

Sailors who served as loblolly boys would also have the grim job of holding patients down while their limbs were amputated - and collecting the limb afterwards.

Nowadays, the equivalent would possibly be a medical assistant with the Royal Navy - no special qualifications are needed before training, and there's a starting salary of £20,000. Or a similar role on a cruise ship - P&O describes the position as a "one-of-a-kind experience" as the medical staff look after patients with health problems "from sunburn to cardiac arrests".

Loblolly is a term not often used today, unless you're a keen reader of Patrick O'Brian's Master and Commander or the Hornblower series of books. The porridgey mess also became a synonym for "swamp" and thus gave its name to Loblolly pines and Loblolly Bay.

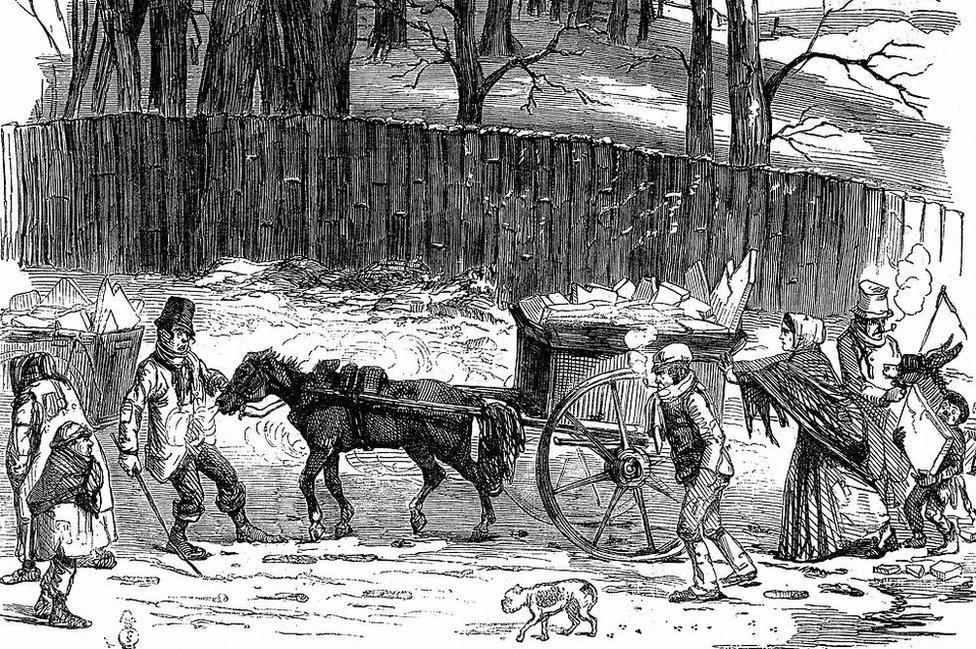

Ice harvesters

Ice harvesters would brave the frigid ponds to gather their stock

Cold winter mornings would see both carts and men on foot, trudging along the country roads to the north of London that led to Highgate, Hampstead, or Enfield. The ponds at those locations were the best sites to reap ice.

Using hooked poles and pickaxes, ice harvesters broke the frozen water into convenient pieces, and "with icicles dangling from the fringe of their ragged trousers, turned up higher than their knees, they plash and dabble in the deadly cold water to bring the ice ashore", wrote Greenwood in the 1870s.

Individual ice harvesters would then help pack the carts for fourpence a load, and as quickly as possible the ice-carters would take their haul to one of London's ice wells - which were about 72ft (22m) deep and had a circumference of about 42ft (13m). The well at Islington held 3,000 tonnes of ice. The ice trade with fishmongers and butchers would then begin when the weather was warmer.

This was originally the ice house for the Holland Estate in Kensington and Chelsea, before it was converted into an exhibition space

The home-harvested ice would be used up by the end of July and many of the well owners also had interests in ships trading in icy areas. A block of Norway ice (sold by the hundredweight) was almost twice as expensive to buy as rough ice from the suburbs.

Ice is still for sale in London, although nobody has to go wading with pickaxes to get it. Instead, Central Ice, for example, which is based in Lewisham, uses reverse osmosis to turn its water into "crystal clear" ice. It produces 7,000kg of ice a week, cutting 35,000 pieces by hand. A block measuring 50x25x25cm retails for £30.

Badgy fiddler

Boy trumpeters and buglers, known as "badgy fiddlers" or "badgies", were a fixture of the British army for centuries. It's thought the word badgy comes from the Hindi "baju", meaning "music".

They were used when there were no other means of notifying large numbers of soldiers that they were required for various duties. From reveille to lights-out, the boy trumpeters sounded calls for all activities of the day.

About 3,000 of them were trained at the Grand Depot at Woolwich.

During the mid 1800s, the bugle replaced the trumpet as the main means of signalling, and after the invention of radio, the trumpet was relegated to a ceremonial role.

The specific calls for trumpet and bugle, with regimental variations and instructions - ranging from warning the officers to dress for dinner to telling the artillery to withdraw at sunset - were published in 1914 by the War Office., external

The British army currently has a Royal Corps of Army Music, made up of 13 regular bands and a string orchestra. New recruits can expect a salary of £15,985 during training, and presumably no longer have to toot a special tune to remind the commanding officer to put his smart clothes on.

- Published31 May 2016

- Published27 March 2016