Erin Pizzey: The woman who looked beyond the bruises

- Published

Warning: This article contains descriptions some readers may find upsetting

Fifty years ago, the first sanctuary for "battered wives" opened its doors. It went on to become Refuge, the UK's largest single provider of help for those experiencing domestic violence.

Erin Pizzey, the woman who began it all in a small house in west London, later developed a theory that would lead her to leave the organisation and decry feminism. She now campaigns for men's rights.

What happened?

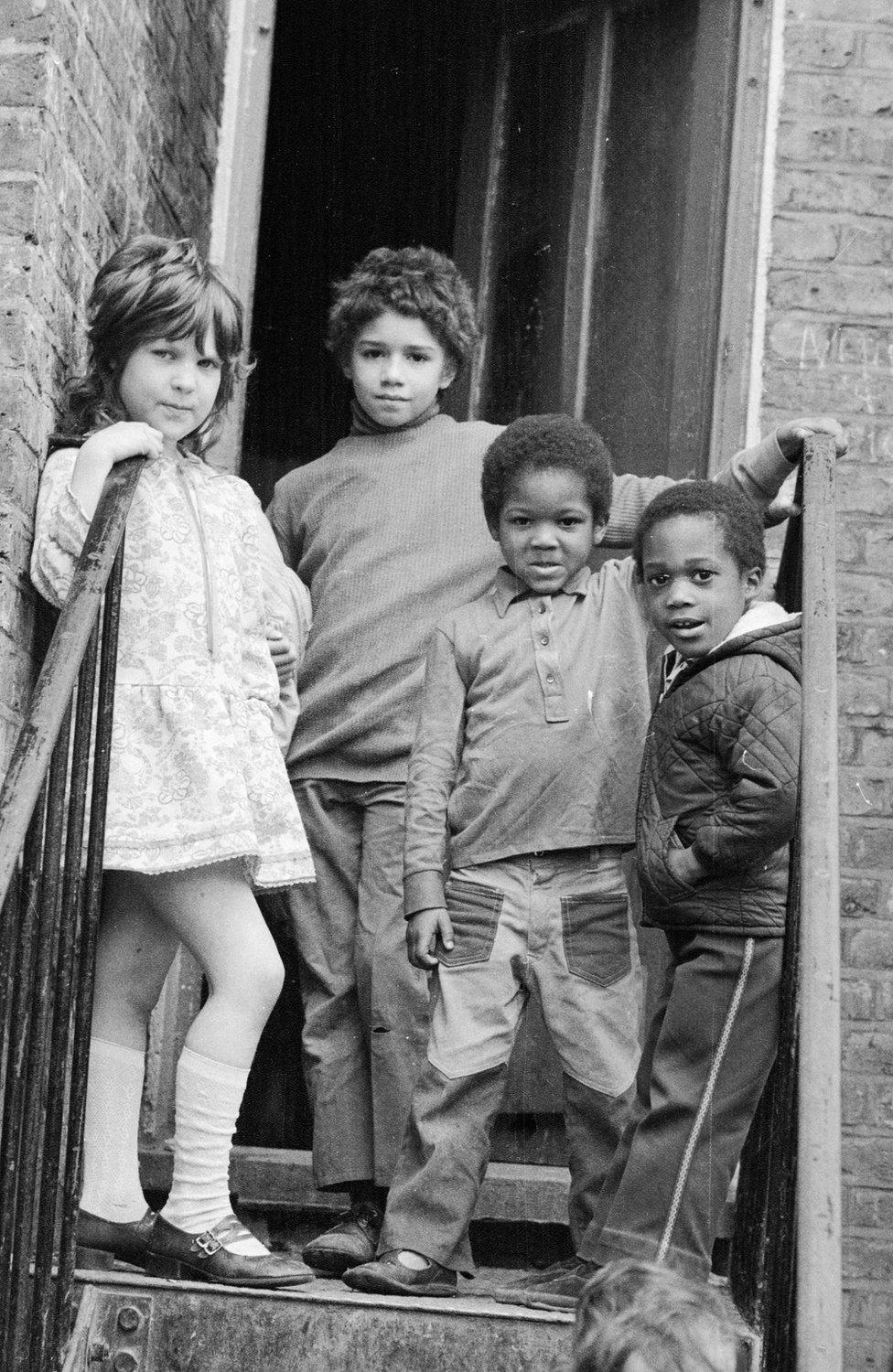

Up to 32 children at a time in eight beds were crowded into a bedroom in the original refuge

Cases of women being murdered by strangers tend to make the news, and we are reassured by being told these circumstances are very rare. And it's true. The majority of murdered women are killed by people they know; most of those by a partner or ex-partner. It is far more likely that a woman will spend her last moments bleeding out on the living room carpet than fighting off a nameless assailant in a park.

Why is this reassuring? For most of us, it is because closing the front door behind us means we are safe. For others, though, that door doesn't just keep danger out. It keeps it in.

Half a century ago, when it was the done thing to avoid catching the black eye of a woman with bruises or a split lip, there was no legal provision to ensure a victim of domestic violence could remain in the family home and the perpetrator move out. There were no refuges, and it was difficult for a woman to rent a flat by herself - even if she could afford it. Police largely turned a blind eye when it was "just a domestic". So that woman, with her black eye and broken ribs and cigarette burns, would stay.

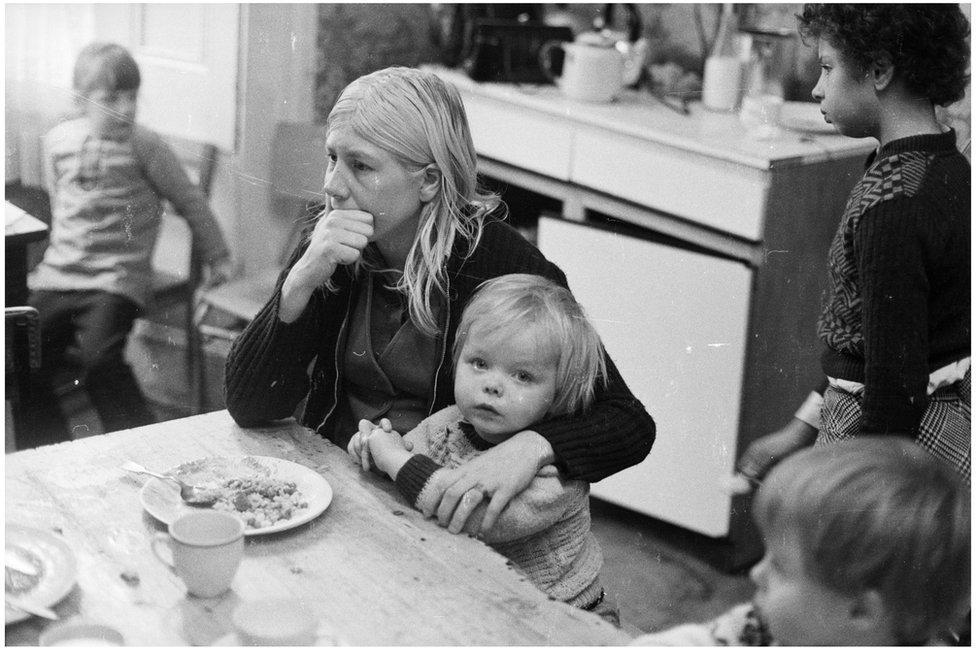

The shelters were run along the lines of a ramshackle and happy commune

November 1971 was damp and foggy. There was a pile-up on the M1, killing nine people. Led Zeppelin released Stairway to Heaven, it was about the time that Spaghetti Junction was opened, the seventh James Bond film - Diamonds Are Forever - was released, and the first of the Mr Men books was published.

Yet it was still 20 years before marital rape became a crime, external; 10 years before a woman had the right to be served at a public bar, external; and three years before the Equal Credit Opportunity Act, external was passed, stopping lenders from requiring women to have male co-signers on loans.

It was in this climate that women passed through the doors of Chiswick Women's Aid. They shared common experiences: fear, loneliness. Nowhere to go, nobody to turn to. An air of broken resignation.

In a matter-of-fact tone, one woman remembers: "He strangled me once. He had me over the end of our settee, hitting me and all I could remember in the end was all this blood. Thick, slimy blood coming out of my mouth.

"He said after, he knew that was the moment I was on the line between life and death. And his eyes were very cold, very scary. And he was smiling."

Erin Pizzey in 1979

Meanwhile Ms Pizzey, "a bored mother of two with a pathological hatred of housework", was feeling increasingly isolated. Her husband often worked away, and she decided to start a social centre for women near her home in west London. Somewhere for a cup of tea and a chat, and support navigating the benefits system or accessing healthcare.

One day a woman arrived with her children and a body covered in boot print-shaped bruises. "No-one will help me", she said. The phrase touched a nerve with Ms Pizzey, who remembers feeling the same way when she was a teenager.

Born in China at the beginning of World War Two, the daughter of parents who didn't like each other or their children, Ms Pizzey describes a troubled, itinerant childhood.

Cyril Carney, her father, was a diplomat and an alcoholic. After China, he was variously posted to Iran, South Africa and Senegal, his family trailing after.

Chiswick Women's Aid put discreet notices in the newspaper so victims would know there was help available

Of her parents, Ms Pizzey says her mother was the more physically abusive towards her, and beat her until blood ran down her legs. She was cruel and manipulative, with a barbed tongue.

Ms Pizzey's father was perhaps more straightforward. He was an angry, violent man who looked up to his own angry, violent father. He was a heavy smoker as well as a drinker, and refused to take baths as he believed they were "weakening". He was easy to smell, another trigger for Pizzey.

Having returned to England in the 1950s, Ms Pizzey's mother died. Rather than have his wife buried, Mr Carney arranged to have her laid out on the dining room table. He and his children would visit the body every evening for six days to watch the progress of decomposition.

"I distinctly remember there was cotton wool sticking out of her nose," Ms Pizzey says. She asked the neighbours to help her bury her mother, "but no-one would help me".

She also found the lack of compassion shown by the community to her childhood self "disturbing". She says: "I would never be one of those indifferent neighbours and turn my back on those in need."

And so, as that first woman peeled off her jumper to show her emaciated figure, red and black and blue with injuries, and uttered those same desperate words, Chiswick Women's Aid was unexpectedly born.

One of the reasons many women did not leave violent households was the fear of abandoning their children

Nobody seemed prepared for how much demand there would be.

Notices were placed in newspapers, reading: "Victims of domestic violence? Need help?" alongside a telephone number.

It was a literal lifeline for Jenny, another early client. She snipped the ad out and hid it under a corner of the carpet so her husband would not find it: "He would have killed me."

She had already approached her GP and even her priest, trying to find a way to leave her husband.

She was told to "kiss and make up" with the man who had beaten, cut, burned, bitten and tried to drown her. She had near-constant black eyes and was painfully thin. Her pleas for help were ignored, even as she was kicked and punched in the street while heavily pregnant.

Women arrived at the shelters covered in injuries

Ms Pizzey felt her first sense of "home" when she was sent, with her twin sister, away to school in England. In the school holidays they boarded at St Mary's Guest House in Dorset, where a number of children with parents abroad were presided over by a Miss Williams, living like a large, happy, ramshackle family.

"If it was sunny, we were given a packed lunch in the morning, and allowed to run free all day. We were treated like puppies," Ms Pizzey says.

It was an approach echoed in the refuges. They were run along communal lines, with everyone mucking in. Housework and childcare were provided by the women. Important decisions were made by vote.

"We filled every place we opened, as soon as we opened. We had women sleeping against the walls with their heads between their knees and children like sardines on mattresses on the floor; we cooked for everyone using food donated by local businesses and just tried to keep spirits high."

Local businesses donated food for the women and their children, some of whom had nothing but the clothes they were wearing

Women who arrived at the original Belmont Terrace location bore cigarette burns, scalds, bite marks, and bald patches where their hair had been ripped out. Some had sickening internal injuries caused by horrific sexual assaults.

Within weeks, 18 women and 46 children were living in the house in Chiswick, sleeping top-to-toe on shared mattresses. It may have been crowded, noisy and with no personal space but it was safe.

One resident at the time said: "The violence itself isn't as bad as the fear. Not knowing what mood he's in when he's coming up the street. Not knowing if you're going to get a hiding." She was blinded in one eye when her husband beat her and caused a detached retina. He didn't allow her to go to hospital.

This too, resonated with Ms Pizzey. She knew what it was like to come from a domineering household. She can remember "freezing" when she heard the warning note of her father spitting phlegm into the flowerbed immediately before putting his key in the lock.

But the refuge's open-door policy soon meant the two-up, two-down in Chiswick was nowhere near big enough.

The women from the refuge squatted in a number of locations, including the Palm Court Hotel in Richmond

Ms Pizzey, then a writer married to a television reporter, had media connections which helped propel the issue into the spotlight.

Every borough she approached for help refused, so the group started squatting, taking over any unused house.

"The police couldn't do anything because it wasn't illegal then - and no council would want to have to rehome 15 mothers and their children every time. We even squatted in the 47-suite Palm Court Hotel in Richmond."

Police often treated husband-on-wife violence as "just a domestic"

Ms Pizzey parted ways with the charity in the early 1980s after a disagreement revolving around feminism and her belief it was "anti-man" and forced women into the role of victim.

Her childhood was prominent in her mind when "feminists started demonising all fathers", as she puts it. The memories of both parents "reminded me of the truth - domestic violence is not a gender issue.

"I have never been a feminist, because, having experienced my mother's violence, I always knew that women can be as vicious and irresponsible as men."

Her stance now on domestic abuse is that violence is a family issue, usually intergenerational, and men and women are equally capable and culpable of it.

Ms Pizzey believes violence is a "family issue" and intergenerational

In her book Prone to Violence she argues that a significant proportion of domestic violence happens because both partners are "addicted" to the adrenalin high connected with fear and being feared.

"Some women were unable to stay away from violence, however much they claimed they wanted to. They seemed doomed either to return to their violent partner, or, having given him up, to move rapidly on to another violent man."

Now 82, she believes that to equate emotional abuse with violence "insults every battered wife", external, a stance disagreed with by abuse charities., external

Some of the women who lived in a refuge on Marlborough Road, Chiswick

She is now editor-at-large of the anti-feminist website A Voice for Men. She remains a passionate believer in helping families recover from violence but refuses to differentiate accountability by gender.

Ms Pizzey still mourns the ones who didn't escape. The ones who only exist in old group photos of Chiswick Women's Aid. The missing women now only apparent in the gaps, like bashed-out teeth made obvious in a goofy smile, where it is clear where they should be.

These are the ones who went back, she remembers.

In 1974, she described the refuge's "beloved battered grandmother" who had left her stockbroker husband and graced the refuge "in a chaos of mums and kids, her face covered by wrinkles and a black eye".

She was later kicked to death by her own son, who was himself damaged by the violence he saw in his parents' marriage, Pizzey said.

"I grieve for her."

There was also Rachel, a mother of five, who moved back into her own house even after obtaining an injunction against her husband. He stabbed her to death the same night.

And Bel, strangled two weeks after being won around by her tearful husband's bunches of flowers, and promises that were no more than hot air and manipulation.

With the benefit of hindsight, would Ms Pizzey do anything differently?

She says: "I didn't have a choice.

"You know, one of the hardest things to learn, is peace."

The domestic violence charity Refuge is no longer associated with its founding mother