Christmas food orders in doubt as Farmdrop closes

- Published

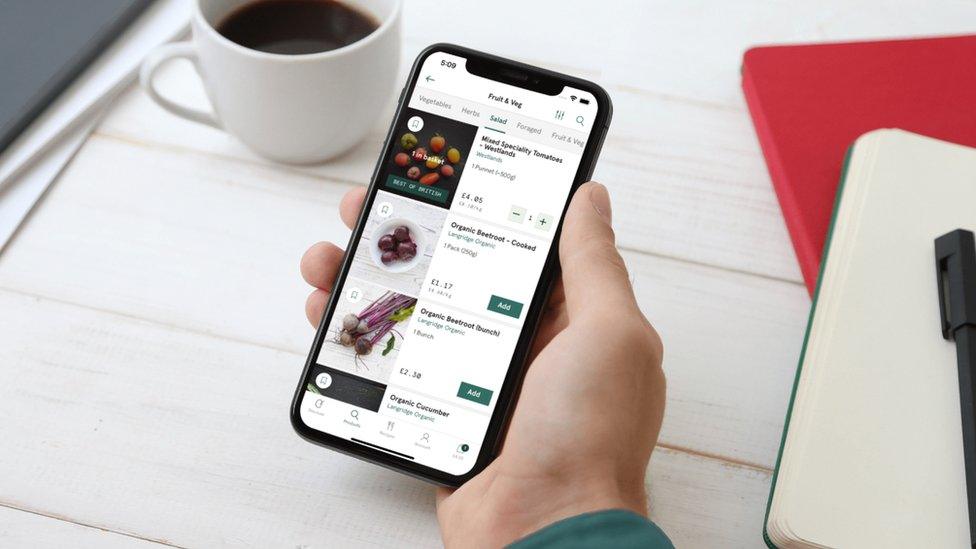

Farmdrop, an online company that delivers food direct from farmers and small producers, has gone bust.

In an email to customers on Friday morning, the firm said that Thursday was the final day of deliveries - leaving many confused about Christmas.

Some suppliers also said they are owed money by Farmdrop but have been unable to get in contact with the firm.

Customers, unsure if they have been let down over their Christmas orders, have shared their disappointment online.

Customer Kate Marfleet wrote on Twitter that she had been charged for a Christmas order which was supposed to arrive on Friday, while others sought advice about where else they could order in time for 25 December.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

The BBC has contacted Farmdrop for a response.

In an email to a customer which was seen by trade magazine The Grocer, Farmdrop advised customers to contact their card suppliers for refunds.

"If you have paid for an order with us, we would recommend getting in touch with your bank or card supplier to initiate a chargeback," the email said.

'Unpaid'

Nicola Simons, founder of fruit preserves and chilli jam producer Single Variety Co, said that Farmdrop still owed her £2,200 in unpaid invoices dating back to August.

"It's absolutely shocking, we've sent three reminder invoices for each unpaid invoice and have had no response from their accounts teams," she told the BBC.

"It's made me really angry and upset as they were meant to be supporting small suppliers but they've caused us much more harm than good."

She added: "They must've seen this coming so why did they continue to order from us, the lack of openness or transparency is appalling."

Kate Clark, founder of the ice cream and custard company Luscious, also said she is been owed money on invoices from May, despite requests for payment.

"The most appalling part of this story is that they continued ordering from suppliers, ourselves included, (many of us small producers) whilst not paying the outstanding invoices," Ms Clark wrote in a Linkedin post., external

In the email to customers, Farmdrop said it had not been able to secure the "support and capital" it needed to survive.

The firm wrote that they had aspired to have a great impact by "influencing change in the food system for the better".

But it said: "It has become apparent that we have exhausted all possible options. It is with very heavy hearts that we must let you know that we will no longer be able to serve our cherished customers."

According to The Grocer, Farmdrop had 10,000 customers in 2020.

At the start of lockdown, Farmdrop saw a surge in demand and its orders doubled.

But despite a spike in sales to £12m during the pandemic, in 2021 the company reported pre-tax losses of £10m compared to £11m the previous year.

In June last year it secured £6m in funding from investors including Wheatsheaf Group, which is part of the Duke of Westminster's Grosvenor Estate as well as Atomico, a fund that was set-up by Niklas Zennström, the co-founder of Skype.

The company, founded nine years ago, had expanded its delivery range last year to a further 2.7 million houses, bringing the total to 7.1 million.

Local supplies

Farmdrop had a network of over 450 producers, but Dr Kate McLoughlin, senior lecturer in supply chain management at Manchester Metropolitan University, was unsurprised by the closure amid wider supply chain problems.

"Even if you have the capital pouring in, establishing local supply chains takes time meaning it's hard to respond to such fast increases in demand."

This is a problem of the wider food system, Dr McLoughlin said, highlighting dramatic increases in transportation costs, fuel prices and driver shortages as possible contributing factors to the firm's closure.

"While they had a huge surge in returning customers, the food system itself is really vulnerable," she explained.

The rising cost of living, spiking energy prices and worker shortages have all combined to increase the pressures on the food industry throughout the pandemic.

Many UK sectors, from petrol stations to supermarkets, have experienced problems with deliveries due to the shortages of lorry drivers.

Food firms have struggled to recruit workers, partly due to the pandemic, but this is also compounded by Brexit, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Farmdrop's orders doubled during the pandemic

Price rises in animal feed coming from abroad have also meant that it is "not necessarily the suppliers, but their suppliers" that potentially had issues along the supply chain, said Dr McLoughlin.

"Cost and speed was great for our supply chain but now the free flow of those materials has changed and transitioning to a local economy means shifting how those systems work," she said.

Related topics

- Published14 December 2021

- Published16 December 2021