London's long-term lav affair: A history of public toilets in the capital

- Published

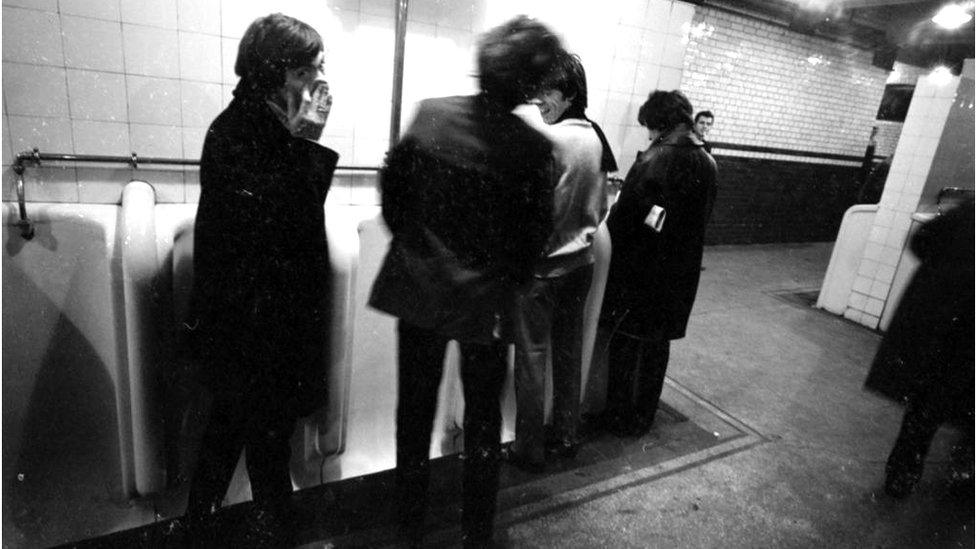

Powdering their noses? The Rolling Stones in the public toilets at Victoria station in 1964

London is home to many fine and famous firsts: the first one-way street; the first commercially made jigsaw puzzle; the first sale of a banana in Britain - and the first public flush toilets.

The provision of lavatories has always been about more than simply somewhere to do one's business. For women in particular, to have access to a toilet outside of the home was something that had to be fought for - both in terms of public facilities and also in many workplaces.

But although they are essential in allowing human society to function, there are fewer public toilets available every year. Some fall into ruin, others have been sold and turned into tiny coffee shops, external or minute art galleries, external.

So, in praise of the public pissoir, here are some of London's toilet-based tales you didn't know you'd been waiting for.

Dick Whittington's giant toilet

"I thought the streets of London were paved with gold, not human waste," as Dick Whittington - illustrated here - might once have said but probably didn't

Public toilets, as you might expect, were fairly rudimentary before the end of the 19th Century. Men - as ever - were able to find a discreet alleyway and relieve themselves there. Women, on the other hand, had to either find a dark corner or go to a communal longhouse.

In 1423, a 128-seat toilet hanging over the River Thames at the mouth of the Walbrook was established by London's first mayor, Richard Whittington. (He is the Dick of talking cat pantomime fame - although it seems he probably didn't have a cat, and almost certainly not one that could speak.)

This "house of easement" was divided into 64 seats for men and the same for women, and is believed to be the first segregated-by-sex public toilet. Its location meant it was washed out by the tide twice a day.

Working-class women could be thus catered for, but for the more genteel ladies, a chamber pot in their curtained carriage was the way to go. If this was not possible, well-heeled women were restricted by their bladder capacity. They had to remain within reach of places they could relieve themselves - either their own home or those of respectable friends or family.

Recurrent mayor of London Richard Whittington gave money to a number of charitable causes - and apparently had an incredibly tiny cat

Monkey closets and money-spinners

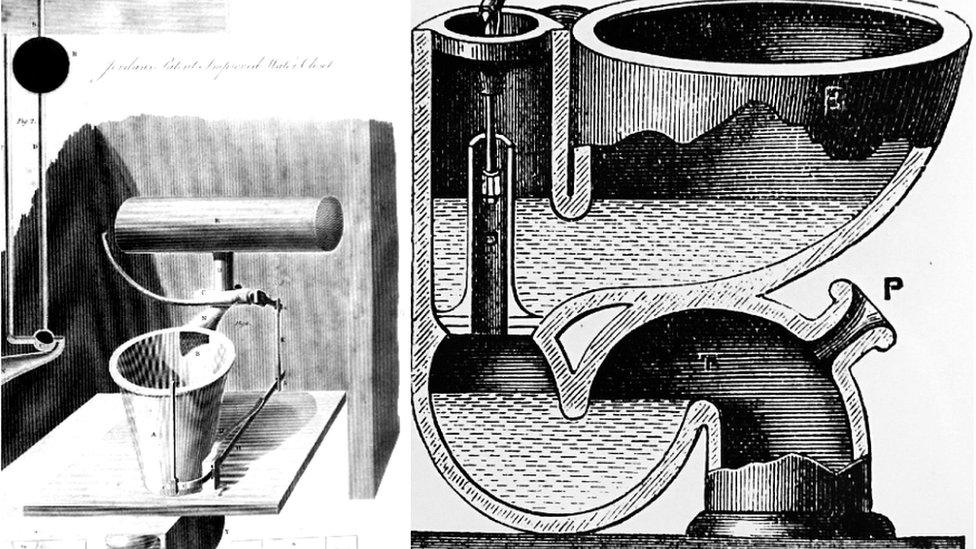

George Jennings installed toilets with the above designs for the Great Exhibition of 1851

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was held at Crystal Palace, where plumber George Jennings installed flushing toilets he called "monkey closets" - a slang industry term inspired by the shape of some of the plumbing. By the time the exhibition closed, more than 800,000 visitors had used the facilities.

Jennings then persuaded the organisers to keep the toilets open. They were quite the earner, generating a penny-a-go revenue that amounted to a yearly income of about £1,000 (a six-figure sum today).

Since those heady days, the city's public conveniences have been through a number of highs and lows.

The urinary leash and the urinette

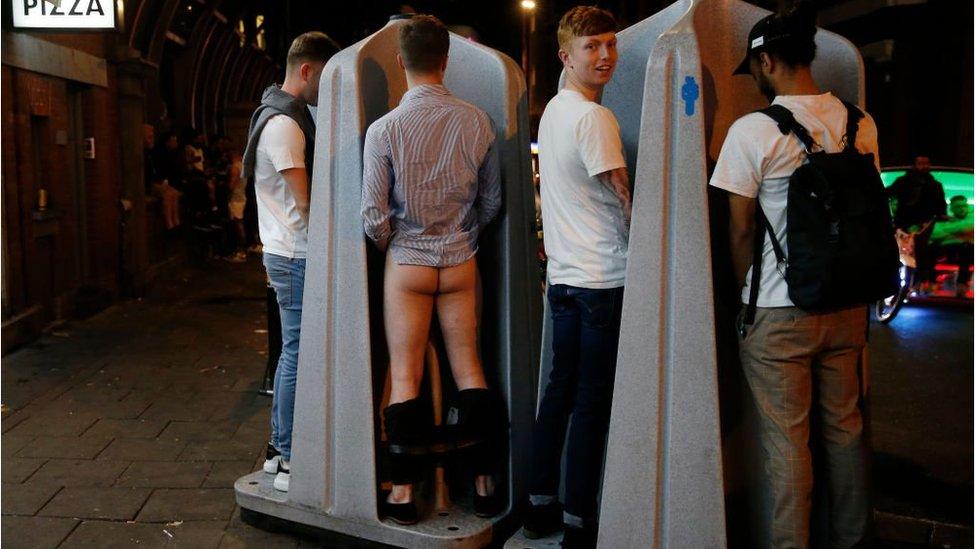

It is still easier for men than women to access toilet facilities - such as these in Soho

By the end of the 19th Century, "public waiting rooms" were more widespread - but were overwhelmingly for men. The so-called "urinary leash" continued to impede women's access to public spaces.

The Ladies Sanitary Association, organised shortly after the creation of the first public flushing toilet, campaigned from the 1850s for "special erections placed in a well-frequented part of the parish" to provide "water closet accommodation for women".

Secretary of the association, Rose Adams, described the "grievous suffering" of women "who naturally find it difficult to ask for public consideration in this matter".

It's true! Women do need to expel waste from their bodies, just like men!

Her urging was backed up by medical (and perhaps even more influential than that, male) advice. Dr Stevenson, the medical officer of health for Paddington, asserted women had "the same physical necessities" as men and the call for female toilets was "no imaginary want created by sentimentalism".

By 1898 the Union of Women's Liberal and Radical Associations had formed. It demanded a public toilet in Camden, where there was already provision for men. This met with opposition: from people who feared it would devalue nearby property; from men who did not want the ladies' facility to be next to theirs; and from those who claimed it would be a traffic hazard.

It wasn't until December 1905, after then-vestryman to St Pancras, the Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw, championed the cause, and a report was published by the Highways, Sewers and Public Works Committee, that the borough agreed to a public ladies' convenience in Park Street.

Inequality continued - even if women could find a public toilet, unlike men using a communal urinal, they usually had to pay. The "water closet" necessary to accommodate a woman and her needs took up much more room and required more maintenance than the simple system for men.

One attempt to get around this was the installation of "urinettes", which were similar to water closets but smaller and had curtains instead of doors. Like a urinal, they were automatically flushed and had limited privacy. They were soon removed, partly because of complaints they were being used in an "uncleanly manner". Presumably unlike the male version, which is well-known for being fragrantly pleasant.

Keeping women in their place (i.e. the home)

World War One saw unprecedented numbers of women enter the workforce - where they needed to access lavatories

The upheavals of World War One saw the greater presence of lone female travellers, and women taking over jobs previously done by the men who had gone to fight. With many fewer men in the factories, women could of course make use of the already-installed toilets. After the war, women were expected to return to the domestic sphere and not "steal" a job from a man.

Workplace discrimination on the basis of sex was outlawed in 1919, with the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act, which made it illegal to ban people from jobs based on their sex. But there was no law about providing toilets - and, according to the Museum of London, many professions used the fact of insufficient female facilities as an excuse for not hiring women.

Since the 1992 Workplace Regulations Act, failing to ensure that men and women employees have separate toilet facilities is unlawful.

What are your rights?

There is no particular right to access a toilet in public, external and local authorities do not have a duty to provide them

Businesses that provide toilets for their customers have no legal duty to do so for non-customers

Workplaces, external must provide suitable conveniences for their staff

Anywhere that offers goods or services to the public must make sure disabled people have equal access, external to their facilities, including toilets

The lav that dare not speak its name

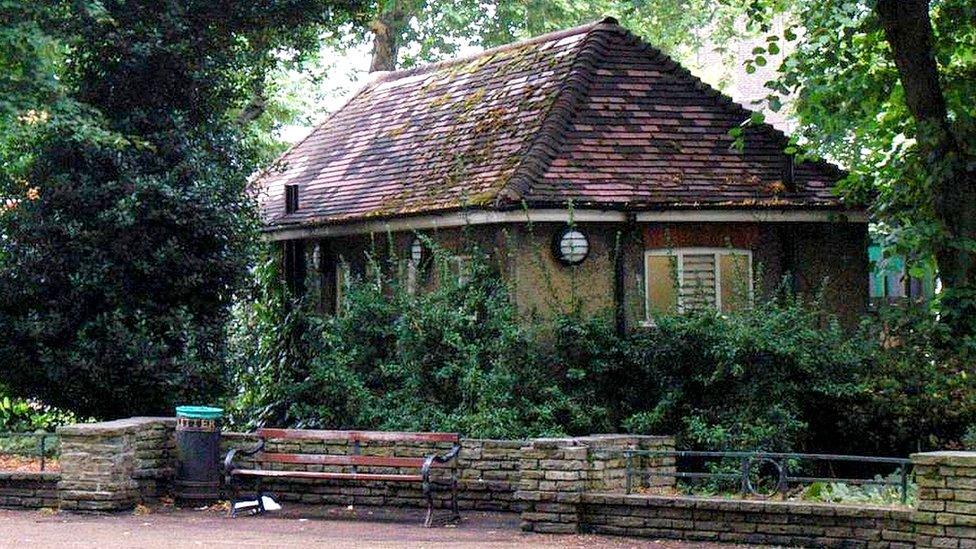

The activity of "cottaging" got its name from public toilets like these in Pond Square, Camden

Public toilets have also had uses other than that for which was originally intended. Cottaging, which takes its name from the small brick and tiled toilets built from the Victorian period onwards, saw men make use of a venue where they were sure to meet other men, and where a degree of personal exposure was common.

The gents' at South End Green near Hampstead Heath - a listed building - is a Victorian underground lavatory block that has been lavishly restored to its former glory.

Star-spotters might like to know it is the place where George Michael was arrested for drugs offences in 2008 - and, according to Historic England, is the "only public convenience still in use that we know was used by [playwright] Joe Orton to cruise".

The actor Sir John Gielgud was arrested in a gents' in Chelsea at a time when the law stipulated that a man could be arrested for merely the intent of committing an act of "gross indecency". He was unlucky enough to encounter an undercover policeman lurking by a urinal.

Fans of Joe Orton can emulate the writer by using the gents' at South End Green

In 1937, a book called For Your Convenience was published by the Limehouse Nights author Thomas Burke under the pseudonym Paul Pry. It was a barely veiled cottaging guide to London's public toilets and detailed the distinctive reputations each had developed.

"If you wanted a piece of rough you'd look round the cottages in Covent Garden," he wrote. "If you wanted the theatrical trade, you would do some of the cottages round the back of Jermyn Street. If you were looking for a good class of trade, you would visit the cottage at Waterloo Station."

Full circle

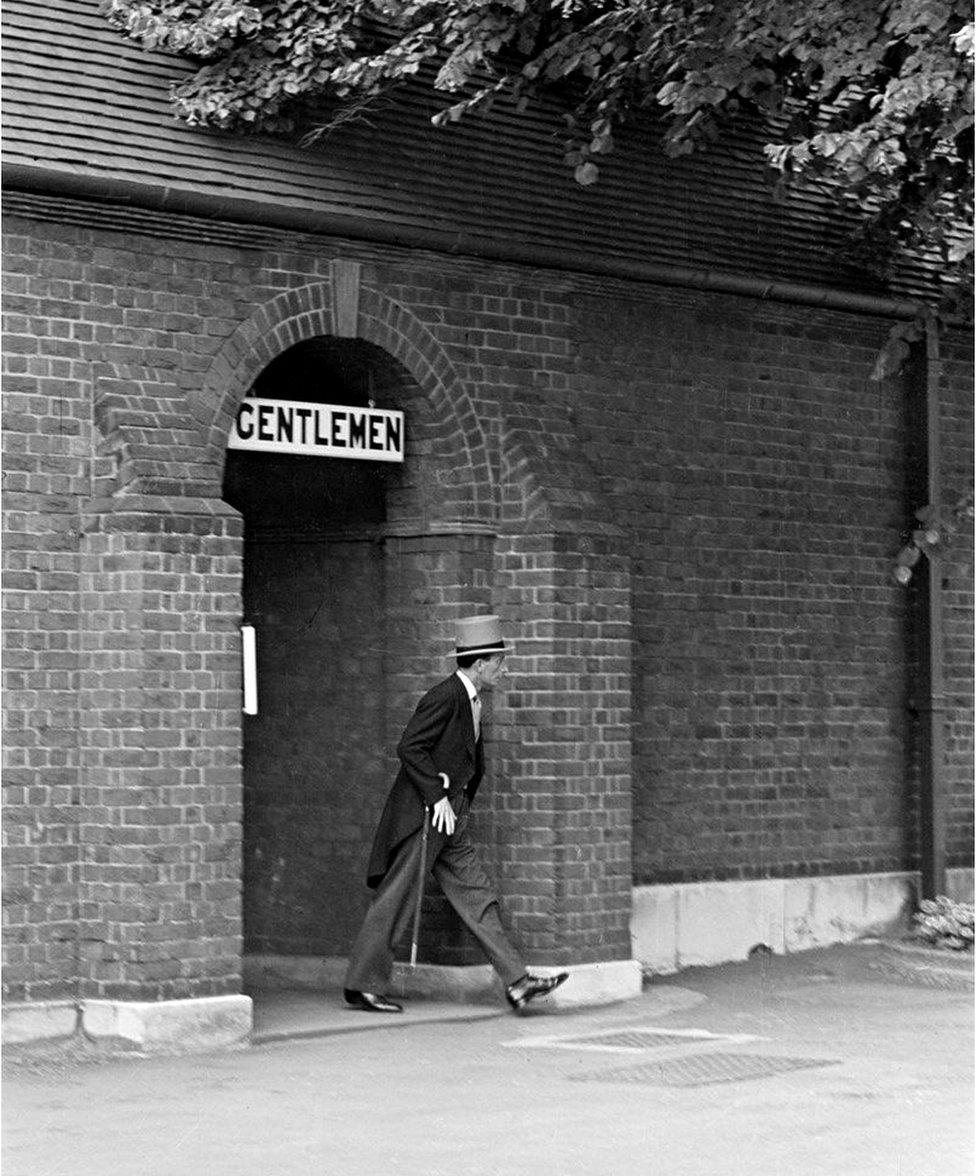

A gentleman leaves the gentlemen's at Lord's Cricket Ground

An 1878 report in medical journal The Lancet highlighted the need for female conveniences, pointing out that "to obtain this much-needed accommodation, some ladies go to restaurants and order refreshments which they do not require, and others to milliners and confectioners' shops. It may be safely assumed that the money thus spent, even when it is only a few pence, cannot always be conveniently spared".

It's a situation familiar to many today - having to buy a coffee in order to get the code to use a customers-only toilet because there are no available public ones. And like in 1878, there is a growing movement of "toilet activists" determined to alleviate the problem.

London Loo Codes, external maintains an openly accessible database with many codes on it, while organisations such as the British Toilet Association, external campaign for better provision. The Royal Society for Public Health argues that public toilets should be considered "as essential as streetlights, roads and waste collection, and equally well enforced by legislation and regulations".