London violence: Children as young as 10 fear being stabbed

- Published

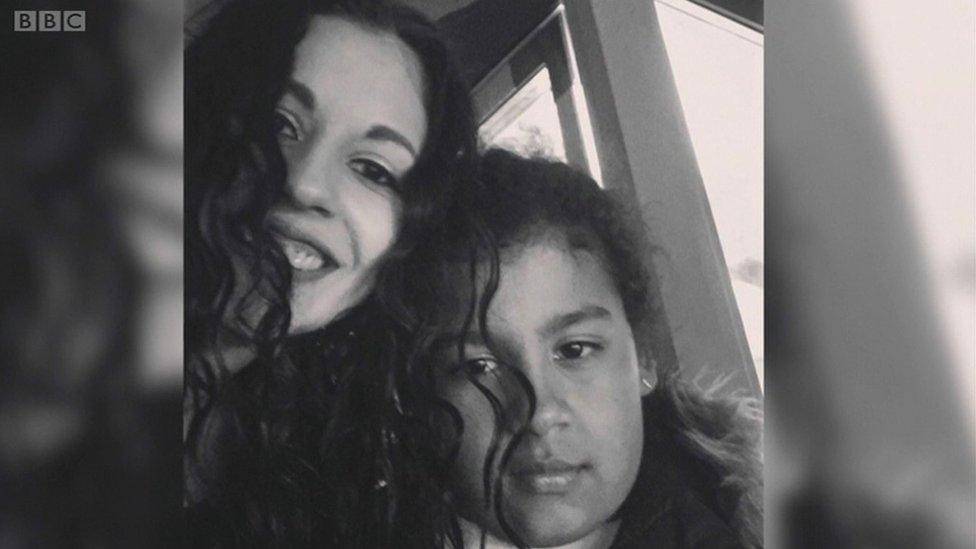

Jermaine Cools, 14, pictured here with his mother Lorraine, was the 27th teenager to be stabbed to death in London last year

London set an unwelcome new record of 30 teenage stabbing homicides in 2021, while a third of all of England's stabbing deaths are reported by the Metropolitan Police.

The picture in the capital is bleak: fearful for their safety, more children are carrying knives, community workers say. Some pupils are so afraid of being attacked they are being shuttled to school by taxi.

What can be done to save young people's lives in 2022?

Activist Tilisha Goupall: "Thirty young people died last year, which is a whole classroom"

At recent crisis talks the BBC attended with police, youth workers and school leaders, community activist Tilisha Goupall recounted the traumatic story of watching her 15-year-old brother Jermaine die on the pavement in front of her. Since his death in 2017 she's worked to try to prevent similar tragedies.

She explained that when she asked a group of children about to start at secondary school what they were most afraid of, "100% of them, all primary school children, said they were [most] scared of being stabbed".

Speaking of the trauma some of these 10 and 11-year-olds have experienced, Ms Goupall said: "Thirty young people died last year, which is a whole classroom."

For the activist, who founded the Justice for Jermaine Foundation, the way to tackle the issue of knife-carrying is to let campaigners like her into schools to speak to pupils.

She said that by telling young people how her brother bled to death, it meant they could relate to the tragedy and, she hopes, will be less likely to carry a knife.

"We try to sugar-coat it but they are already exposed to all this, so we shouldn't sugar-coat it any more."

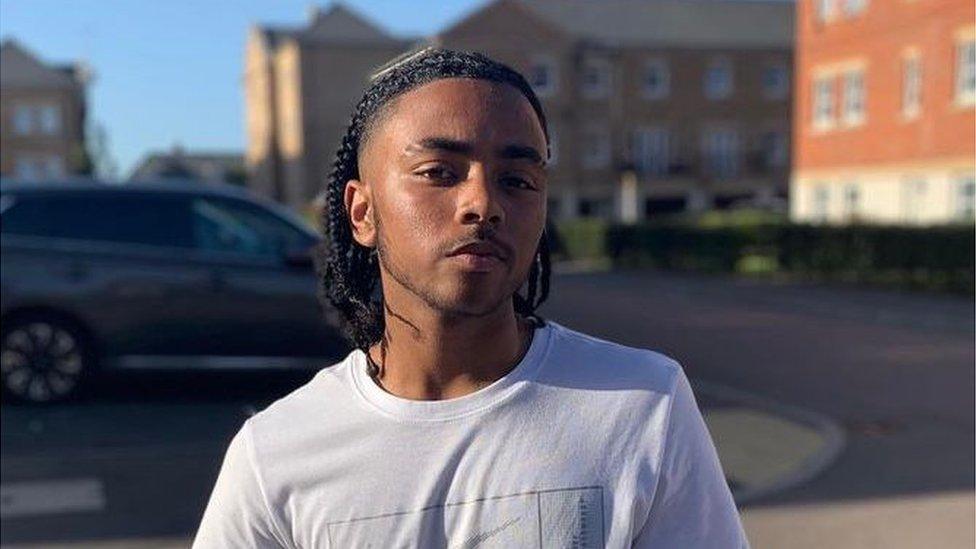

Zaian Aimable-Lina, 15, was killed in Croydon on 30 December - and still was not the last teenage homicide victim of 2021

One of those present at the talks in Croydon, a south London borough where five teenagers were stabbed to death last year, was the principal of Oasis Academy, Saqib Chaudhri.

He has long had reservations about letting activists into his school but said he had changed his mind following the deaths of two of his students in 2021, because he currently felt "powerless".

"I [previously] refused to allow the streets of Croydon into my corridors because I wanted my corridors to feel like a safe space," he said.

"I'm looking at it differently now - I'm thinking how can I get the streets and the community into my school?

"The borough needs to come into every single school for the times the school can't be there."

'He said he would stab me in my face'

"Knife crime is crazy since the summer," according to Aaron Nzita, 19, who explained how he was mugged at knifepoint in September.

Mr Nzita, who works in community engagement, was at a cash machine on Croydon's London Road when he was approached from behind and shoved over a knee-high wall by a teenager.

"This young guy just pushed me over the wall, grabbed me, and said he would stab me in my face if I didn't give him all my money," he said.

"It was really nerve-wracking - I thought I was going to end up in hospital." Luckily, two passers-by approached and the would-be mugger fled.

"Knife crime right now has got everybody on the edge of their seats," Mr Nzita added. "My mum is not letting my little brother out - it just needs to stop.

"Some kids before didn't want to speak to police at all, but now they're frightened so they want to speak to police."

Mr Nzita said he knew of children who carried a knife "just in case".

"Most of these kids are not going to stab someone to kill them, they are just trying to protect themselves and make a statement."

Police officers on patrol are a common sight on Croydon's London Road

Wayne Lindsay, who was also at the meeting at the Croydon Voluntary Action base, is the co-founder of P4YE, a group that supports young people and families in south London.

He said many children felt they could be targeted just for being in the "wrong postcode" and that he knew of various academies calling cabs and minibuses for students who were too scared to walk or take the bus to school.

"It's heart-breaking because it's become more and more common," he said. "I hear it all the time."

However, Mr Lindsay said his organisation was struggling to get access to classrooms to speak to these high-risk children, despite knife possession being an issue in "every school".

He said: "I lost my cousin two years ago so I'd like to be able to go in and support schools - the police can go into schools very easily but it's having people from the community like us that makes the biggest difference.

"The impact is felt by us in the community, and some of the teachers are not necessarily from the community they're teaching in, so sometimes they don't see the problem."

Croydon is one of the parts of London worst affected by knife crime

United by a sense of desperation, it seemed that teachers, community workers - and, significantly, also the police officers present at the meeting - agreed about the need for a change of tack.

Ch Insp Craig Knight said that as far as he was concerned, the activists were "pushing at an open door" to work with schoolchildren, because "we have to do more".

His colleague, Insp Kathy Morteo, said police should no longer be "standing in front of children that don't necessarily look like them, trying to tell them what they should and should not be doing".

And as Ch Insp Craig Knight pointed out, the need for change is urgent.

"In my personal opinion I think the police are doing nothing but keeping a lid on a what is a boiling cauldron," he said.

"We have to better understand it so we can turn the heat down on that boiling cauldron."

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published4 January 2022

- Published19 November 2021

- Published5 March 2021