'We don't train to give care in corridors'

- Published

The BBC saw about 20 patients being treated in corridors at Queen's Hospital, with more arriving

The BBC has visited Queen's Hospital in east London, where patients have had to wait in corridors for as long as 24 hours before being treated on a ward. This is not a localised issue, with similar reports across England; the pressure on the NHS is "intolerable and unsustainable", according to the association that represents doctors.

Medics told us they were working through their hardest winter - even worse than during the pandemic. During a two-hour period on Tuesday morning, we saw about 20 patients being treated in corridors, with more arriving.

David and Wendy Anderson's son Ben, 43, spent about 11 hours waiting to get on to a ward for treatment for suspected sepsis, they said.

Amid such trying circumstances, David Anderson was nonetheless full of praise for the staff here.

"It's been a bit hectic but under the circumstances, we haven't got any complaints at all," he said. "It is tough all round, but I can't praise them enough."

David and Wendy Anderson waited about 11 hours with their son, Ben, to get to a ward

Separately, we spoke to Hannah Newing, who came into the Romford hospital over Christmas with her father, who has early-onset dementia.

She told the BBC he had to wait a day and half to get on to a ward, adding that his medical records were lost and he was not given enough food.

Ms Newing said she saw a lot of patients with paramedics staying with them; the trust that runs Queen's, external ranks second bottom in London in terms of ambulance handover times.

Your device may not support this visualisation

Many elderly patients are coming into Queen's with respiratory illnesses, including flu and Covid. As well as caring for them, staff also need to minimise transmission.

Across the country, the NHS is trying to manage multiple infectious illnesses and post-pandemic demands amid a shortfall of available GPs.

The chief executive at Queen's, Matthew Trainer, tells us that it will not be before March that the pressure eases and staff are able to give uncompromised care.

Alice Kenny has been redeployed as a corridor nurse while the hospital manages ward shortages

One of the workers here, junior sister Alice Kenny, has been redesignated as a corridor nurse for the past two weeks to help those arriving in ambulances.

She said: "We don't train to give care in corridors. It is really not nice and if we were in their shoes, we'd be really upset as well. We're supposed to look after patients like we do our own family and we're not able to do that.

"The morale has been quite low recently, we've not felt as if we've got that support."

She added: "We've got multiple strikes going on. Everyone knows that we've got issues, that's part of the reason we were striking. With Covid, there was support coming from everywhere, the morale was supported by that; it motivated us to keep going.

"We never recovered from Covid. We never had a break and we're very tired. We've been playing catch-up with everyone that couldn't see their GP, with conditions worsened and people are coming in sicker."

Ms Kenny attending to a patient in a corridor

The clinical lead at the emergency department, Dr Ignatius Postma, said the care some people were receiving at Queen's was not what he would want for his own family.

"Arriving here every day and seeing patients outside my office - it's very demoralising," he said. "It's not what I expected when I started out in emergency medicine.

"We try to our best for our patients in the corridors but I don't think it's right, to be honest.

"It's not what I would like to see for my own family, to see them being treated in the corridor, to be treated with people walking past. We try to make it as private and as dignified as possible but it's still not what it is supposed to be."

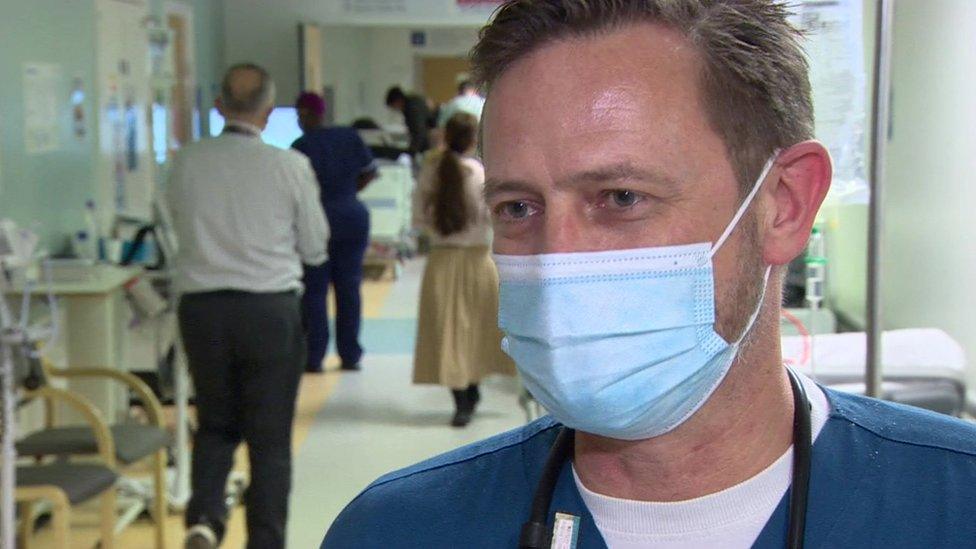

Ignatius Postma says the situation is "demoralising" and "not right"

He added: "What I wish is to have more places and spaces for these people to go to. When we've done our emergency work, they need places to go to get the proper and continuous treatment.

"We can't deny it's not as good to treat a patient in a corridor as it is on a ward.

"At the moment the service is so stretched that we have to use whoever we can to look after patients, so I think patients' care definitely gets compromised - therefore we definitely have to do something about it."

Lead nurse Ruth Green says she feels "at a loss"

Lead nurse Ruth Green told the BBC she felt out of options.

"I feel at a loss about what to do and how to make it better," she said. "Part of my role is trying to make things better for staff and for patients, and I can't see anything that I can do."

As at many other hospitals, one of the major challenges for Queen's is a delay in discharging patients who are medically fit to leave. This is often because of problems relating to care home staff and primary care across the community.

At Queen's about 120 patients a day are typically ready for discharge. This is not always possible though, leading to blocked beds that cannot be used for new arrivals.

The chief executive of Queen's, Matthew Trainer, says it is the worst winter he has seen

Mr Trainer said: "We've got a really big focus on understanding what's causing those delays. Some of that stems from us, getting our processes quicker - everyone has got a story about being ready to go home and having to wait all day until they get their drugs - we need to fix that ourselves.

"We also need to understand why homecare agencies provide those packages of care, and what can we do to fill more of the empty care home beds, which can't be staffed in the area around the hospital.

"Also, what can we do working with primary care so that people don't need to come here in the first place."

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published11 January 2023

- Published10 January 2023

- Published10 January 2023