Ulez expansion: Contested claims examined

- Published

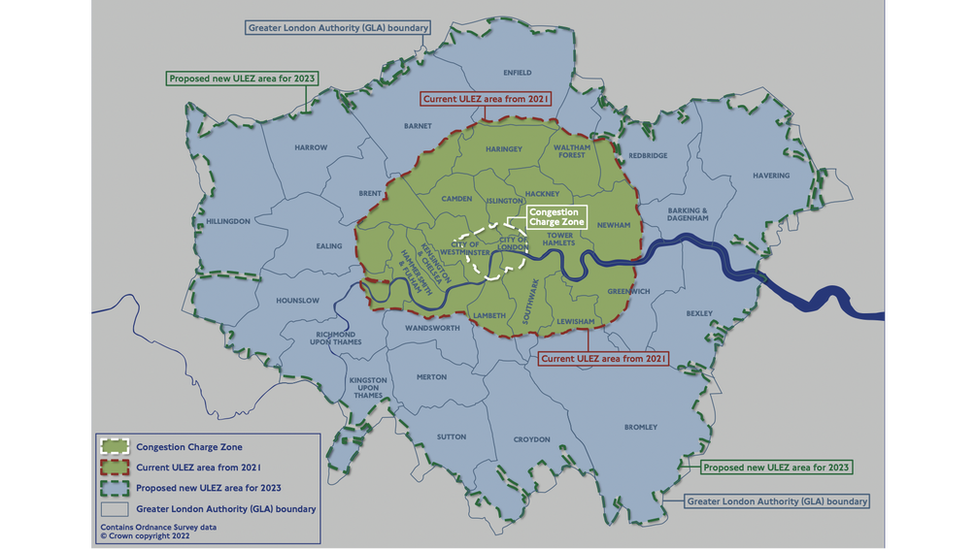

Users of non-compliant vehicles must pay a £12.50 daily charge to drive within the zone

Following a ruling from the High Court, the Ultra Low Emission Zone (Ulez) has been given the go-ahead to expand to cover the whole of London from the end of August, much to the dismay of the opponents of the scheme. The BBC has been assessing some of the claims made about London Mayor Sadiq Khan's flagship clean-air policy to better understand its impact.

'Not enough notice has been given'

Opposition from Liberal Democrats and some Labour councils and MPs focuses on the argument that people need more time to swap their vehicles for compliant ones.

The mayor of London announced his Ulez expansion plan at the end of November, giving people nine months' notice.

The previous Ulez expansion from central London to encompass the North and South Circular roads was announced in early 2019 to come into force in October 2021.

This gave people almost two and a half years to prepare.

Other parts of the country also have clean-air zones. In Bristol, the council submitted its plans to charge polluting vehicles in February 2021, and the policy came into effect 21 months later, in November 2022.

So it is true to say that the latest Ulez expansion is happening more quickly than the previous one and in comparison to similar schemes in other cities in the UK.

'Inflation means it's not a good time to replace a vehicle, and there is a shortage of second-hand cars'

Although it has recently fallen slightly, inflation remains near a 40-year high. At the start of 2023, inflation was 10.1% - it was 4.9% a year earlier.

Annual food inflation hit 16.7% in January and energy prices are twice as high as last winter.

The cost of second-hand cars has also risen.

According to data from AutoTrader, the median price of a compliant Ulez vehicle in 2021 was £12,989. This has now risen to £18,295.

Its analysis also shows in February there were 43,359 Ulez-compliant cars for sale in London with an average cost of £15,000 and £19,991 for petrol and diesel respectively.

Only about 5,000 of these compliant cars are for sale under £5,000.

Within a 100-mile radius of London, there are about 90,000 compliant petrol cars, 8,000 of which cost under £5,000.

The mayor of London says there are 200,000 non-compliant vehicles on the road. It is estimated that 30,000 of those vehicles are vans.

AutoTrader data shows there are only 5,181 vans for sale across London and the South East and 23,803 across the UK that are Ulez-compliant.

So it is true that compared with a year ago it will be harder for some people to replace their vehicles and also that there is a shortage of affordable cars and compliant second-hand vans.

Tom Edwards, BBC London transport and environment correspondent

'The Ulez expansion will drastically improve air quality'

According to Transport for London (TfL) data, external, road transport accounts for 44% of nitrogen oxide (NOx) emissions, 31% of PM2.5 (particulate matter) emissions and 28% of CO2 emissions in London.

It says: "The proposed London-wide Ulez is expected to reduce road transport NOx emissions by 5.4% (362 tonnes) in London. There is expected to be a 1.5% (7.8 tonnes) reduction in PM2.5 emissions from road transport in London."

That is more than the reduction of 240 tonnes of NOx when the Ulez was introduced in central London.

Data from City Hall, reviewed by Imperial College London, shows: "Road transport NOx emissions for all vehicles are expected to reduce by 5.5% (214 tonnes) in the non-Greater London area in 2023 compared to a scenario where there was no Ulez expansion London-wide.

The equivalent figure for road transport PM2.5 is a 1.4% (3.5 tonnes) reduction. For PM10, there is a 0.9% (4 tonnes) reduction. For carbon the reduction is 1.6%."

Of course not everyone will believe this modelling, and City Hall Conservatives have highlighted an independent assessment, external that says the Ulez expansion will result in a "minor" reduction in NO2 pollution exposure, of 1.3%.

Some critics of the scheme use this figure to say the expansion isn't worth it, but what City Hall and health experts say to that is that there is no safe level of pollution. What's more, many clean-air campaigners think the mayor is not going far enough.

World expert on air quality, Prof Frank Kelly from Imperial College London, said expanding Ulez would improve the health of Londoners.

"There is nowhere in London still that does meet the WHO (World Health Organisation) air quality guidelines, so that means everywhere you go the air you are breathing is having some impact on your health," he said.

Other cities are trying different ways to reduce the number of vehicles on the road and to cut pollution.

Paris, for example, is next year banning private cars from most of the city.

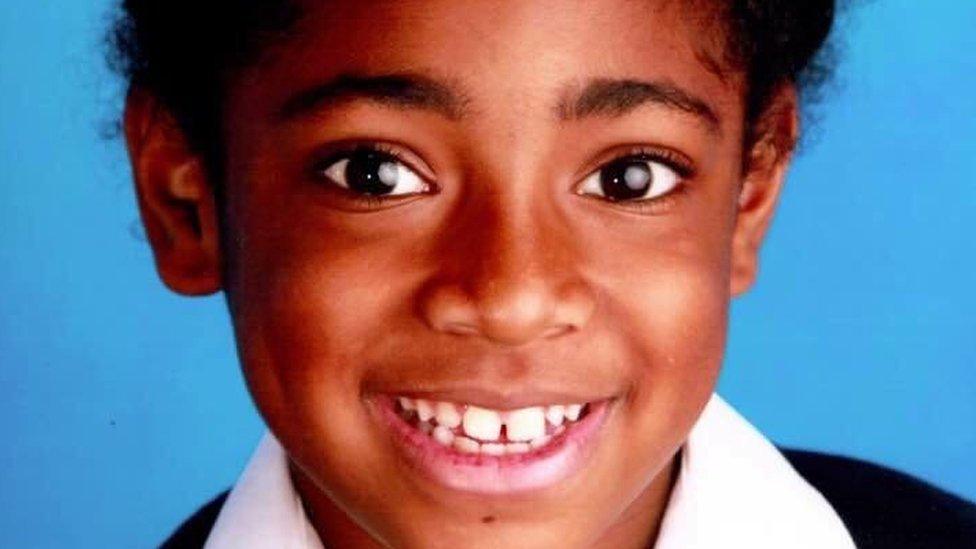

Ella Adoo-Kissi-Debrah was the first person in the UK to have air pollution listed as a factor at an inquest

'About 4,000 Londoners die prematurely each year due to toxic air'

Simon Birkett from Clean Air in London has highlighted Imperial College research, external - commissioned by City Hall - that says: "In 2019, in Greater London, the equivalent of between 3,600 to 4,100 deaths (61,800 to 70,200 life years lost) were estimated to be attributable to human-made PM2.5 and NO2, considering that health effects exist even at very low levels.

"This calculation is for deaths from all causes including respiratory, lung cancer and cardiovascular deaths."

So how do they get to that figure? The WHO recommends a relative risk of a 1.08 increase for 10 micrograms per cubic metre (ug/m3) of PM2.5.

If in 2019 there were 50,000 deaths in London - combined with the capital's annual average of PM2.5 at 10 ug/m3 - there would be 8% x 50,000 attributable deaths to PM2.5s, i.e. 4,000.

Who is affected by pollution within those premature deaths varies significantly.

For instance, people who have cardiovascular disease (CVD) would have their lives shortened much more by pollution - someone with heart problems could lose two years of their life, while a healthy adult would see their life shortened only by a few days.

City Hall says there is also research that shows 550,000 Londoners will develop air-pollution diseases by 2050. , external

And, as health experts keep saying, the main point is in all of this: there is no safe level of pollution.

Experts say what we really should be discussing is the impact of pollution on people's lives - from asthma to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) to dementia - and comparing real pollution levels in the capital with WHO guidelines.

And so the often-quoted "4,000 attributable deaths" in London is best seen as a statistical construct to try to make the impact of pollution easier to understand.

Ulez: Mayor confronted by heckler over zone expansion

'Over 1m people outside London will be affected and there is no support for them'

Data from DVLA, analysed by the Liberal Democrats, shows that out of the 5.8m cars registered in 10 counties near London, 1.6m are not Ulez compliant.

Only the cars driven into the capital will be affected by the expansion, of course, and not all of them will be.

The TfL scrappage scheme only applies to people living in London.

The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs is in charge of the air quality grant scheme that allocates money to local authorities to work on projects including low-emission transport schemes.

The scheme for 2022-23 has awarded funding for 44 projects to a total of £10.7m, none of which has gone towards scrappage schemes in the home counties.

So it is true to say there is no financial support for the people living near London to replace their non-compliant vehicles.

Fears as emissions zone expands to north Kent boundary

'The scrappage scheme is the biggest ever in the UK'

The original scrappage scheme introduced in February 2019 consisted of a £61m fund. A further £110m was added to the scheme on 30 January, bringing its total to £171m.

It was extended again on 4 August with an extra £50m from City Hall reserves to offer all Londoners with a non-compliant car up to £2,000 to replace their vehicle on a first-come first-served basis.

Extra help for small businesses. charities and people with disabilities was also included.

The money pledged for the scrappage scheme before 4 August came entirely from TfL, which is a government-funded body. However, in this instance, the £110m given to the scheme was provided to TfL by the Greater London Authority.

This total of £221m committed compares with a £42m scrappage commitment by Bristol and £10m in Birmingham.

However, Bristol's population is about 500,000, compared to London's almost 9m.

If the scrappage scheme was looked at on a population basis, for London to match Bristol it would need to spend about £370m.

Therefore, while it is true to say that this is the UK's costliest scrappage scheme, Bristol has the better claim to being the biggest such project.

Tim Donovan, BBC London political correspondent

'The government has the power to stop the expansion'

According to Section 143 of the Greater London Authority Act (1999), the government can force the mayor to change his transport strategy if any element is "inconsistent with national policies relating to transport" and is viewed as damaging to anywhere outside of London.

While there is a particular impact from Ulez on the counties surrounding the capital, in practice there would appear to be a number of reasons why the government would not block the expansion, particularly given its commitment to similar schemes elsewhere.

Transport and air quality are devolved areas for a reason - it is held that these policies are best devised and championed at a local level.

This is the extension of a policy originated by London's former mayor Boris Johnson, and is one that the government implicitly endorsed when it agreed a funding deal with Mr Khan in August.

Any measure taken by the government in relation to London would, City Hall argues, involve preventing all cities from charging people to drive within their boundaries.

Therefore, while it is true the government has the ability to override the policy, it appears to be a very unlikely outcome.

A majority of cars driven in London are Ulez-compliant

'There is a legal challenge against Ulez'

Four Conservative-controlled London boroughs - Bexley, Bromley, Harrow and Hillingdon - and Tory-run Surrey County Council - tried to halt the expansion through the High Courts, but on 28 July lost the judicial review.

There were four grounds that the judicial review was heard on:

The mayor did not comply with legal requirements because they treated the latest project as an extension of the existing Ulez rather than a new self-standing scheme

The mayor's approach to consultation with areas outside Greater London in relation to the scrappage scheme

Unfair and unlawful consultation in relation to expected compliance rates in outer London

In terms of the scrappage scheme, there was "irrationality" due to uncertainty and inadequate consultation

In his ruling, High Court judge Mr Justice Swift said the mayor's decision to expand Ulez "was within his powers".

The councils say they will not be appealing against the ruling, decision, but have described it as "incredibly disappointing".

Sadiq Khan answered questions about Ulez at People's Question Time in Ealing

'90% of vehicles are already Ulez-compliant'

This was the claim of the mayor and Transport for London (TfL).

They said that nine out of 10 cars seen on automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) cameras driving on an average day in outer London were compliant.

There was an unknown number of cameras at the time the claim was made, as TfL would not disclose how many were in use.

Update - July 2023

In June, following a complaint, the UK Statistics Authority asked the mayor and TfL to provide data supporting the claim that nine out of 10 cars seen on automatic number plate recognition (ANPR) cameras driving on an average day in outer London were Ulez-compliant. TfL has now published limited data, external, but did not tell the BBC how many vehicles in total were captured on camera and how many came into the capital from outside London.

In July, TfL disclosed information about the number of cameras used to lawyers for the five councils seeking to challenge the Ulez expansion at the High Court. It shows the mayor's claim was based on data from 106 cameras in outer London. By comparison, more than 1,100 cameras capture data in inner London, a smaller area. The Conservative-led councils have questioned the reliability of the outer London camera data and argue the information should have been released during the consultation last year so it could be challenged. Their barrister alleges "the non-disclosure of the ANPR data information was unfair and unlawful".

Separately, TfL released information about cars registered to addresses in outer London. This is based on figures from the Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders.

It shows 84% of cars in outer London comply with emissions standards, which means that at least 280,000 cars - or about one in six - do not.

Labour councils object to mayor's ULEZ plans

This is thousands more cars affected than the mayor originally said. Mr Khan says data on registered cars isn't what TfL has ever used and he says the camera data is a better gauge.

So the 90% claim of compliance for vehicles owned and driven in outer London does not seem to be supported by the available evidence.

Some cities in the UK other than London have introduced similar clean-air zones

'The government has funded low-emission zones in other cities, but not London'

The government has allocated over £300m to local authorities under the Clean Air Fund.

This money supports a range of measures to improve air quality, and it can include spending on vehicle scrappage schemes.

London does not receive money from the Clean Air Fund as air quality is a devolved issue.

The government says it has provided TfL with £6bn in funding support to keep public transport moving, an additional £2bn towards vehicle grants and infrastructure to support the rollout of clean vehicles across the country and another £102m for projects specifically targeted at helping to tackle pollution.

So it is true that the government has not funded London's low-emission zone through the Clean Air Fund, but TfL has shared in central government grants aimed at tackling pollution.

'If your car isn't up to date, you've had it'

'People in outer London are more dependent on their cars'

Within the existing Ulez, only 17% of journeys are made using a car, with almost 50% made via public transport.

However, in outer London, 44% of trips are made using a car and only 30% on public transport.

In seven boroughs in London, a higher percentage of journeys are made by car than the average 44%.

Car ownership is also much higher in outer London - 69% of households have access to or own at least one car, compared with 42% in inner London.

So it is true that people in outer London rely more on private vehicles.

'This is the most radical clean-air policy in the world'

Many cities are taking steps to improve air quality and while it's hard to say definitively that London's is the most radical policy, it is certainly one of the most ambitious.

Apart from London, two cities in Europe are said by observers to be in the most restrictive category - at least until Paris's new policy comes into force.

In Madrid, since November there has been a zero-emissions zone, which is about the same size as the current London Ulez.

However, residents are given an exemption so they can continue to use their existing car until they get a compliant one.

Oslo also has an ambitious scheme: it has a zero-emissions zone in the centre and has removed 700 car-parking spaces to create bike lanes and small parks.

If you want to check if your vehicle meets the emission standards, you can do so on the Transport for London website, external.

Broadly these are the non-compliant vehicles:

Motorbikes that do not meet Euro 3 standards (pre-2007 vehicles)

Petrol cars and vans that do not meet Euro 4 standards (pre-2006 vehicles)

Diesel cars and vans that do not meet Euro 6 standards (pre-2015 vehicles)

Buses, coaches and lorries will need to meet or exceed the Euro VI standard or pay £100 a day

If your vehicle is not compliant, you have a choice of either paying a daily charge of £12.50 to drive within the zone, replacing your car or finding another way to travel.

Those eligible for help from the mayor's £110m scrappage scheme can get up to £2,000 for scrapping a car or up to £1,000 for scrapping a motorcycle. For wheelchair-accessible vehicles there is a grant of up to £5,000.

Money from the scrappage scheme can be claimed if you are:

On a low enough income and/or are on disability benefits

A sole trader, "micro-business" or charity with a registered address in London that uses a van or minibus - there are grants of between £5,000 and £9,500 available in this category

This story was first published on 15 March and has been updated to provide further context. The BBC will continue to update the article to reflect new developments.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk

- Published23 February 2023

- Published16 February 2023

- Published30 January 2023

- Published24 January 2023