The last lockdown rough sleeper living in a hotel

- Published

Paul Atherton buys fresh socks and underwear every six weeks

Thousands of rough sleepers were taken off the streets and housed by the government when the first Covid-19 lockdown was announced. Three years later, one man has yet to leave his "temporary" accommodation.

Just after the UK was locked down for three months in April 2020, author and filmmaker Paul Atherton found himself living in a central London hotel.

He'd been sleeping rough for 11 years, after losing his rented flat on the South Bank due to an error on his credit file.

He'd spent the last three of those years wandering central London by day, and at night sleeping across the seats at Heathrow Terminal 5.

Mr Atherton became one of thousands of homeless people on the street who were housed under the government's Everyone In scheme, which gave emergency accommodation to 37,000 people to keep them safe during the pandemic, according to the charity Crisis.

He said: "I was using Terminal 5 as my bedroom. I was there prior to Covid breaking out. I was there with what turned out to be just over 300 people across the terminals. Nearly everybody there worked.

"They got up in the morning and they just went about their day, and came back at midnight or 1am and slept on the seats, then got up the next morning and carried on like everybody else would."

Heathrow was popular with rough sleepers when the first lockdown was announced

The large number of people needing accommodation exposed the true extent of rough sleeping prior to the outbreak to be four times higher than estimated.

"Out of nowhere, on 1 April a team was sent out with not much guidance and said 'get everybody from the airport into hotel rooms'. And that was the first time I was engaged with what later became known as Everyone In."

Mr Atherton made a video diary of his experience as part of a documentary called 90 Days of Hope, external. It explored whether providing temporary accommodation and helping people to engage with agencies could end rough sleeping for good.

But with no national directive and insufficient funding to continue the scheme, as well as a lack of affordable housing for people to move into, most councils were forced to close this emergency accommodation after a few months. Many rough sleepers found themselves homeless once again.

Rough sleeping in London has gone up by more than 20% in a year, from 8,329 people between April 2021 and March 2022 to 10,053 people a year later

But not Mr Atherton. He is the last person in the borough of Westminster whose hotel room is still paid for by the council as part of the original scheme.

There were 10,053 rough sleepers in London last year, up more than 20% in a year, according to data from the Combined Homelessness and Information Network, which was commissioned and funded by the Greater London Authority (GLA).

The filmmaker's room is clean but sparse. There's a double bed, a modern bathroom and a lovely view across Paddington Green.

However, there are no cooking or laundry facilities or storage. There is a small, empty fridge under the desk by the window. Mr Atherton buys five new T-shirts, five pairs of underpants and five pairs of socks every six weeks from Primark.

It costs up to £250 a night to house him in his central London hotel, where he has been staying continuously for the past 14 months.

This pays for a room and breakfast but no other meals. And it's not always the same room. Sometimes Mr Atherton has to pack up and move to a different room in the hotel, because the one he has been living in is booked online by someone else.

Paul Atherton frequently has to move rooms

But it also means that the local council is paying tens of thousands of pounds a year to house him, with no longer-term solution in sight.

"It all comes back to this stupid notion of budgets," he said. "Under the housing benefit budget they have a cap. And that cap is lower than our cheapest rent in Westminster.

"Under the Everyone In budget and rough sleeping budget, they seem to have no caps and therefore they can spend whatever they like housing people so if they are going to try and house people, the government and legislation has forced them to spend these ridiculous sums of money."

Westminster Council said: "The council provided accommodation for 266 people facing homelessness through the 'Everyone In' scheme, which ran throughout the pandemic.

'Chronic fatigue syndrome'

"We have gone to considerable lengths to support Mr Atherton over several years and have recently made an offer of permanent accommodation within Westminster. This offer includes additional support to accommodate any disability he may have.

"It is disappointing that, to date, Mr Atherton has refused to engage with this offer."

Mr Atherton says he suffers from chronic fatigue syndrome and requires a carer and a wheelchair-accessible home for periods when he can't walk. Until that can be found, a hotel room suits his needs, he says.

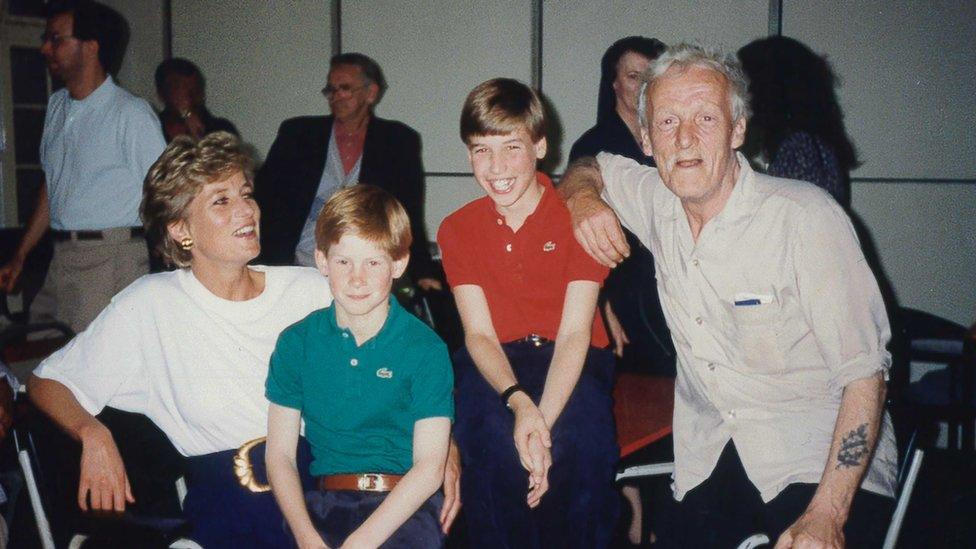

Earlier this week, Prince William launched a five-year campaign to end homelessness, which he says should not exist in a "modern and progressive society".

Prince William with his mother and brother at The Passage homelessness charity in 1993

The Prince of Wales's charitable foundation is putting in £3m of start-up funding in a bid to make homelessness "rare, brief and unrepeated".

The government has made a manifesto commitment to end rough sleeping by 2024.

Meanwhile, Mr Atherton has been told his 14-month stay at a hotel near Edgware Road is coming to an end.

It is fully booked up for the tourist season, and he'll need to find a new hotel to house him from next week.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published27 June 2023

- Published26 June 2023