How London's environmental policies have shaped the capital

- Published

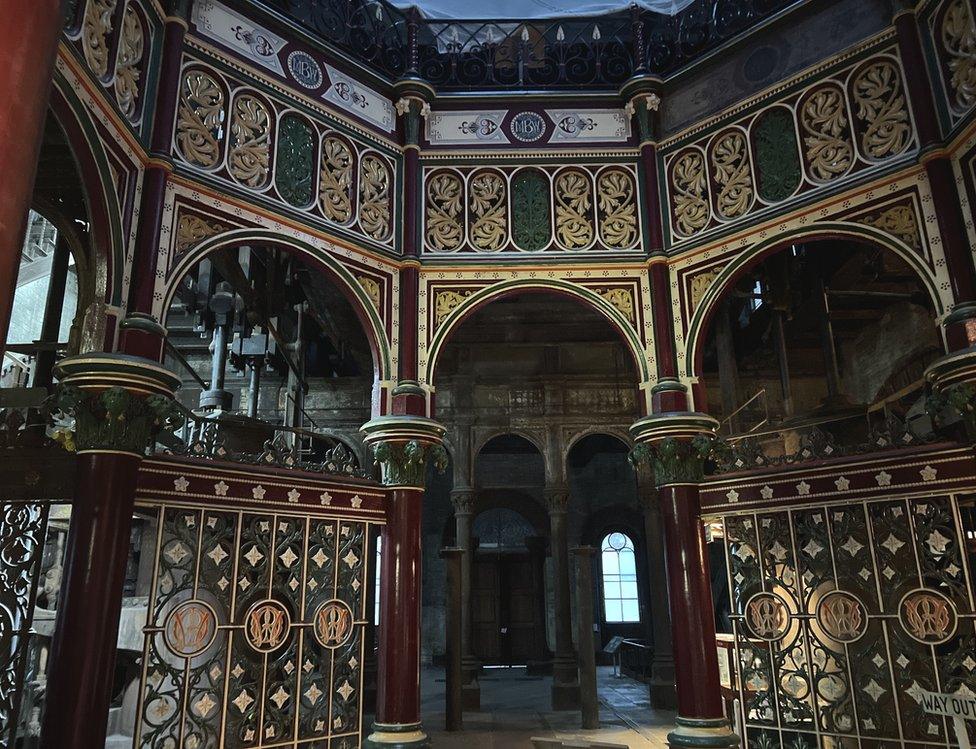

Victorian engineering like Crossness station was the pumping heart of Bazelgette's work

London has a long history of being out at the front of global public health innovation.

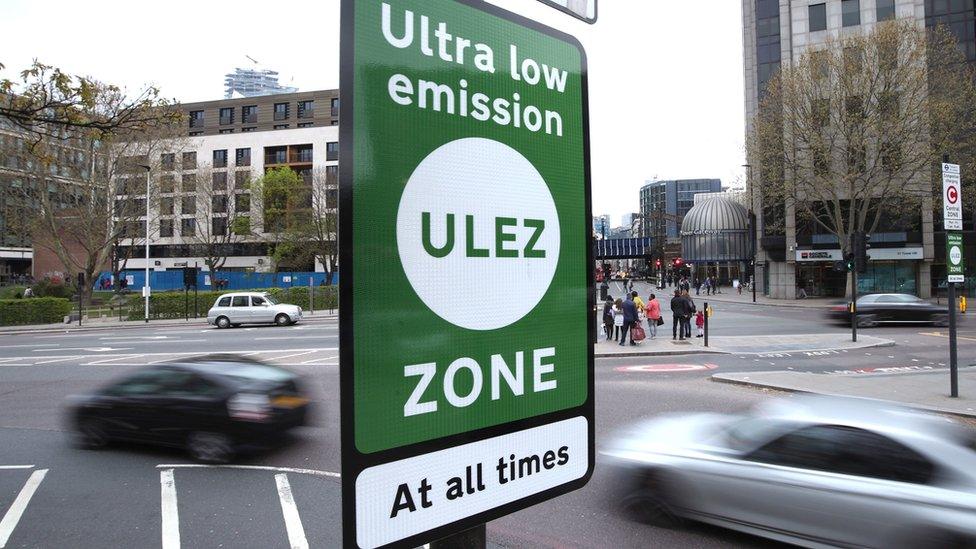

The latest proposal is the expansion of the Ultra Low Emission Zone (ULEZ) to cover the whole of London.

So can history provide clues to how the completion of the city's low-emissions jigsaw is likely to go?

If we go back to 1858, the Thames was a putrid, toxic sewer full of human excrement and waste from factories.

It led to the Great Stink and the smell was so bad that parliament was suspended.

Punch cartoon from 1855 shows scientist Michael Faraday meeting Father Thames

As a result the authorities accepted a proposal from Joseph Bazalgette to create a huge sewerage system, which is still in use today.

Some argue that Bazalgette should be seen as a hero of London. But there was opposition at the time from people who lost their homes as a result of the building work and from river traders.

Bazelgette's Crossness Engines pumping station in Abbey Wood is still in use today

A distant cousin of the Victorian sewers is the super sewer, or Thames Tideway tunnel, which is being built today to stop sewage overflows going into the Thames. Opposition to that has centred around the ideas that that it is not needed and is too expensive.

In terms of air quality, 1952 saw the Great Smog, in which thousands of Londoners died from a combination of sulphur dioxide emissions arising from coal-burning and a weather pattern that meant the pollution was not blown away, as it usually was.

Following that fetid event the government introduced the Clean Air Act. It established smoke-free areas throughout the city and restricted the burning of coal. It also led to a big improvement in air quality.

The government of the time was initially reticent to act, amid suggestions that it could not afford to do so and that the less well-off would suffer because they would not be able to heat their homes.

Claire Harding, interim chief executive at the Centre for London, external, said: "I think one of the things we can learn from all of that is that things can get better and things can get better very quickly.

"If you put a Victorian Londoner in the city today they'd be astonished how clean things are, how sewage is dealt with safely and hygienically underground and how low air pollution is.

"For people who were brought up in the era of the coal fire, today's London would seem very clean and that shows we can do better. But we are starting from a pretty good place."

With the creation of the London mayoralty in 2000, came a renewed focus on pollution policies in the capital. Arguably the congestion charge introduced by the then-mayor Ken Livingstone in February 2003 was in the same policy bracket.

The congestion charge was introduced in February 2003

Yes, it was for improving congestion. But it was also about reducing pollution and improving the lives of Londoners. It was based on a scheme in Singapore but was also bigger and perhaps more radical.

The congestion charge was challenged in court by Westminster City Council, which said it would lead to an increase in pollution on the boundary roads. The High Court dismissed the objection.

Professor Tony Travers, from the London School of Economics, said that anti-pollution measures were accelerated with the creation of the mayoralty. "Only local government will do this kind of thing. National government is afraid to take on the electorate so it requires local politicians, with the power to argue things through, to make changes of this kind."

The congestion charge was in Ken Livingstone's manifesto in 2000 so Londoners knew what they were voting for.

Initially it cost £5 a day to drive a vehicle in central London. Ken Livingstone has said that he instigated it because business groups were complaining that the city's road congestion was making trade difficult.

In 2007 he expanded it to cover west London - known as the western extension - and there were many demonstrations against it.

Nearly doubling the size of the congestion charging zone was unpopular in west London

Livingstone tried to go further with a CO2-based emissions-charging scheme. At the time it was known as the "Chelsea tractor charge" as the owners of larger, more carbon-emitting vehicles would have to pay. But it was challenged in court by Porsche and never implemented.

In 2008 he also introduced the Low Emission Zone (LEZ), which was the world's largest at the time, for trucks and buses despite the freight industry and London's councils saying the scheme would have a "barely perceptible impact on air quality" but would place a disproportionate cost on taxpayers and business.

Prof Travers added: "I think there are things we can learn, looking back to earlier efforts to stop pollution. Most obviously the congestion charge in 2003 and the Clean Air Act in the 1950s. But you can go back to the 19th century and the building of the sewers in London.

"These were all, at the time, controversial projects that had their opponents. But, of course, now people just take for granted that these were the right things to do."

In 2008 Livingstone lost the mayoral election to Boris Johnson, who had a different approach to environmental policy.

Ken Livingstone and Boris Johnson clashed over the expansion of the congestion zone

Mr Johnson scrapped the CO2-based emissions-charging scheme and the western extension. In 2009 he also delayed the application of the LEZ standards for vans and minibuses on economic grounds. Around this time, concern over nitrogen oxides and particulate matter started to increase.

Drivers had been encouraged to buy diesel vehicles to lower CO2 emissions - but toxic nitrogen dioxide levels had increased. The EU had started to threaten cities with fines if they failed to clean up their air.

During this period there was a trial on Lower Thames Street - where there is a pollution monitor - to "stick" particulate matter to the road using dust suppressants. There were also trials of green walls and bushes to reduce pollution. Neither was an overwhelming success and public policy revisited the idea of treating pollution at source.

In March 2015 Mayor Johnson then announced he was introducing the "world's first" ultra-low-emission zone (ULEZ) in central London. His introduction date was 2020. At the time, clean-air campaigners thought that timetable was far too slow but Transport for London began considering how to introduce it.

Double-decker electric buses were introduced by Mayor Johnson

The present mayor, Sadiq Khan, brought that start-date forward to April 2017. He called it the "toxicity charge" - or T-charge - for an area of central London that overlapped with the congestion-charging zone and described it as "the world's toughest emission standard".

He was also urged to ban diesel vehicles completely (because they were the source of much of London's toxic nitrogen dioxide) but said he did not have the power to do so.

Simon Birkett, from Clean Air in London, external, said: "When there are big problems, like the Great Smog or diesel, you need big solutions. And when you have big solutions you typically have debate about them - and that's healthy. But crucially you also need political leadership.

"The politicians of the day need to say 'this is a real problem. It is unacceptable that we are letting people die early or have stunted lungs'. Then we need them to take action. And [in London] when they take action we have seen that these measures have worked."

The T-charge was replaced by the ULEZ in 2019 and expanded to cover the area within the north and south circulars in 2021. Now the proposal is to expand the ULEZ to cover the whole of London in August 2023.

ULEZ protesters have been loud in their opposition

Ms Harding said: "I think there will always be opposition because whenever there's change there are winners and losers - even if we think there's going to be more winners than losers in the long term.

"But that's not to the say that the objections people have aren't serious and valid. There have been some changes - like the western expansion of the congestion-charging zone - that never did happen. But I think the benefits of change become more obvious with hindsight and perhaps the fears don't materialise as much as people thought."

Many other cities are on the same path now as London. Glasgow, for example, has introduced a Clean Air Zone. Opponents of pollution policies say they go too far, supporters say they don't go far enough.

If history shows us one thing, it's that when it comes to London's direction of travel, broadly it is towards a cleaner and less polluted environment.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk

- Published30 June 2023

- Published26 June 2023

- Published1 June 2023

- Published21 February 2020