Oxford Street: Is it facing demise or resurgence?

- Published

The nature of shopping on Oxford Street is changing - but is it for the better?

Known as the nation's high street, Oxford Street in central London has long attracted domestic shoppers and tourists.

But with the pandemic, hybrid working and the phenomenon of US-themed sweet stores putting pressure on the street's popularity, is it facing a demise, or heading into a resurgence?

For several decades it has been a destination for international shoppers and brings in an outsized chunk of London's retail, so it's important to the city that Oxford Street does well.

But according to retail expert Jonathan De Mello, the pandemic impacted the street "substantially".

"In 2019 [Oxford Street] was the pre-eminent street in Europe for retail," he said.

By comparison, footfall there is now about 20% down according to the New West End Company, which represents Oxford Street's businesses, partly due to fewer people returning to work in nearby offices.

Selfridges has been a mainstay on the street since 1909

Pre-pandemic, Thursday and Fridays were Oxford Street's busiest days, thanks to office workers, whereas now the weekend is busiest with highest footfall and spending on Sundays, despite shorter opening hours.

Compared with last year, footfall on Oxford Street east is 30% up, 7% on the west side, mainly thanks to an increase in international visitors, New West End Company says.

The average time spent there is two hours, it says, with the value of the average transaction being about £125.

The opening of the Elizabeth line in 2022 added 1.5 million more people across London within a 45 minute commute of the West End, City and Docklands, according to New West End Company, while Tottenham Court Road station is now busier than Oxford Circus, data from Transport for London shows.

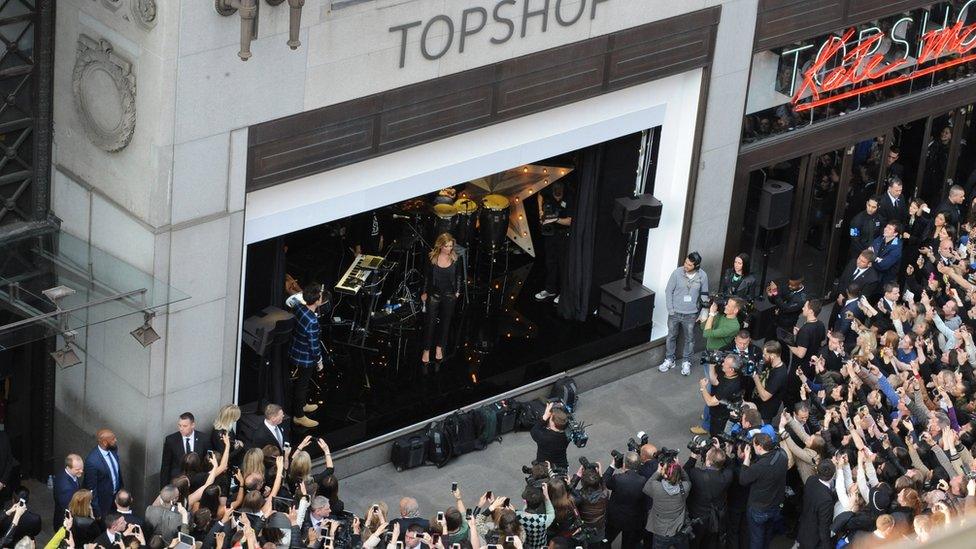

In its heyday, Topshop at 214 Oxford Street saw supermodel Kate Moss attract huge crowds

If you took a stroll along Oxford Street as the country was easing out of covid lockdowns, you would have seen empty shops as many brands closed for good - Topshop being the most obvious thanks to its former spot on Oxford Circus.

'Spiral of decline'

The pandemic also saw the emergence of so-called US-themed sweet shops, as food stores were the only ones legally allowed to trade.

Geoff Barraclough, the councillor at Westminster City Council responsible for the area's planning and economic development, said the authority soon learnt they "weren't really food stores".

"The majority have fictitious directors, the majority have no intention of paying the business rates, many are selling counterfeit goods - and quite often illegal vaping equipment as well," he said.

He added the council had been working with landlords to try to prevent them from leasing their properties to the "candy stores" by offering to install local entrepreneurs or start-ups on a temporary basis.

About 300 start-ups have applied for the spots, according to the council.

Westminster has also offered to forgo some business rates, however about "half a dozen landlords" were not cooperating with the initiative, Mr Barraclough said.

US-themed sweet shops are 2% of Oxford Street's trading floor space, the council says

There are also concerns the sweet shops were undermining the street's brand.

According to Mr De Mello the shops are creating a "negative spiral of decline" that is deterring other retailers.

"They now feel that Oxford Street is not the place to be," he said.

"A candy store is not a retailer they want to sit beside as it has negative connotations, it attracts the wrong type of shopper and creates a feeling of disrepair."

Some US-themed sweet stores are selling out-of-date products

But Mr Barraclough argues this is not the case and says the US-themed sweet shops occupy only about 2% of the street's retail-floor space.

This is a sentiment shared by Sarah Jaconelli, director of campaigns at the New West End Company.

She says the proliferation of candy stores is partly the product of short-term leases which are being offered because of large-scale development work.

"You won't get the serious brands taking short leases," she said.

"When planning permission [is being sought], only short leases are available - so that's when the candy stores and souvenirs shops come in."

Empty shops are difficult to fill on a short-term basis

'Appetite is there'

New West End Company figures suggest there are 27 empty shops on Oxford Street at the moment, six being the subject of long-term development plans and the rest being let pending refurbishment or other work.

"The [candy stores] will slowly move out," says Ms Jaconelli. "It's just that these things don't happen overnight. Leases take time to negotiate, shop fit-outs take time to happen.

"We're confident we'll fill the empty shops. If you speak to the agents, they say the appetite is there."

High-end retailers are choosing Regent's Street instead, says Jonathan De Mello

Ms Jaconelli points to eight mixed-use developments, new flagship stores and retail concepts plus six nearby hotel developments, as examples of the street being on the "cusp of a new dawn".

"There is so much going on. Anyone who knows Oxford Street isn't worried about its future," she said.

"Oxford Street is the most famous and busiest high street in the UK and it is going through a once-in-a-lifetime transformation. It's going to look very different in five years."

Part of this change is a £90m redevelopment led by the council, focused on improving the street's overall "appearance and usability".

The plans are in the consultation phase and offer improved pedestrian safety as well as better lighting and paving, plus more greenery and seating.

Space will also be created for more al-fresco dining, a sector that is growing on the street.

The plans include seating areas along the street

How the buildings will be used is also changing, according to Mr Barraclough.

"No-one's going to walk up four flights of stairs for shopping any more. So the upstairs are being turned into offices," he said, adding that businesses now look for offices that are high quality "with good net-zero credentials".

He said ground floors will probably still be used for retail but basements will be transformed for leisure activities, a formula that the former Debenham and House of Fraser buildings are abiding by.

However when the Marks & Spencer store at the Marble Arch area of the street tried to do this, it was denied planning permission and the government stepped in.

"As a council, we want to encourage landowners to retrofit, extend and refurbish their buildings, rather than demolish and rebuild," Mr Barraclough said.

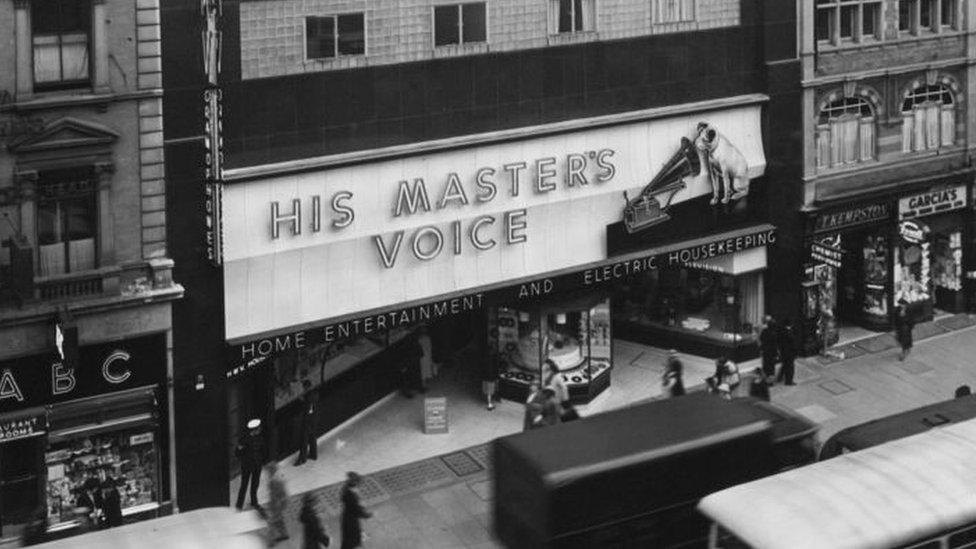

HMV, once the jewel in Oxford Street's crown, will return later this year

Maybe the state of Oxford Street can be summed up by the store at number 363.

From 1921 it was occupied by HMV, back in the days when people used to buy music rather than stream it.

When music-industry retail began to change in the 2010s, the shop downsized only to move back again in 2013, then closing in 2019.

The empty spot was snapped up by a US-themed sweet shop. But then earlier this year it was announced that HMV will be returning, armed with a new "retail experience" and selling pop-culture merchandise as well as music.

A nod to the past with an eye on the future - something that seems to sum Oxford Street up well.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published18 January 2023

- Published21 September 2022