The Old War Office reveals secrets as it becomes a luxury London hotel

- Published

The Old War Office was built using 25 million bricks and 26,000 tonnes of Portland stone

For nearly 120 years the grand arched door of an enormous opulent building in London's Whitehall remained firmly shut to the public.

Known as the Old War Office, it was a place of work for some of the most famous political names of 20th Century Britain, while also acting as a meeting point for spies and military bosses.

Now rebranded The OWO, it has been turned into a luxury hotel and residences. But what used to go on behind the huge stone walls of the Grade II*-listed building?

In 1899, work began on an extraordinary new headquarters for the War Office - now more diplomatically known as the Ministry of Defence - on a site where the Palace of Whitehall had once stood.

Finally completed seven years later and at a total cost of more than £1.2m (almost £123m today), it was created in a style known as Edwardian Baroque with elaborate turrets, columns and statues adorning the majestic Portland stone exterior.

The minister of war had one of the grandest offices in the Old War Office

"This building was built at a time when London was conscious that it was falling behind other imperial capitals," explains architectural historian Clive Aslet.

"The centre of London was being rebuilt on a bigger scale in a flamboyant style that was going to show off the British Empire."

Within the thick fortress-like walls were more than 1,000 offices connected by 2.5 miles (4km) of corridors, much of it wide enough so that messengers, often boy scouts, could cycle on bikes around the building to pass on notes and post.

Parts of the insides of the building were as regal as the exteriors, with a flamboyant marble staircase at the centre of the building that led up to the offices of secretaries of state and military heads.

"When you first walk into the space, you feel as if it's almost like... it's a Viennese opera house where you've got this kind of awe-inspiring detail and ornate work in terms of panelling and light," says Geoff Hull, director of EPR Architects, which has overseen the restoration of the building.

The grand staircase was only for the use of secretaries of state and military bosses

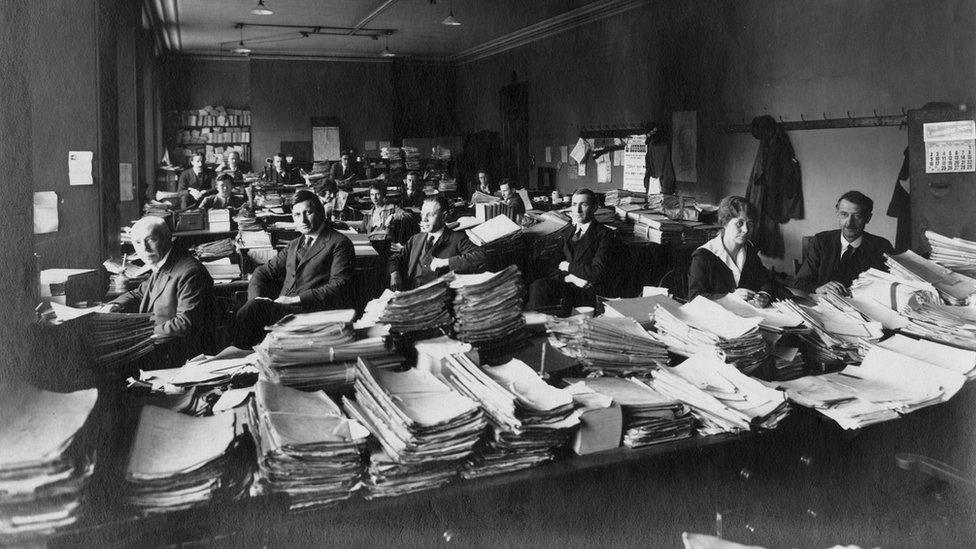

Yet not all of the building was quite so impressive. While those in charge discussed military operations beneath chandeliers and decorated ceilings, the offices and rooms occupied by civil servants and service workers were somewhat plainer.

"We realised quite early on that the second floor was where all the key decisions were made, and then all of the other floors were more clerical activity where they were just purely plastered walls," Mr Hull explains.

And it was from these opposing surroundings that Britain's military administration was run.

For the first few years, some 2,000 people were based within the building but before long increasing numbers were being crammed in as the War Office became the command centre for the country's efforts during World War One.

The offices for civil servants were rather plainer than the more regal parts of the building

Given the size of the building, not surprisingly, not everything ran entirely smoothly.

Reflecting on the time when he took over as director of military operations in 1914, Sir Charles Callwell wrote about how, over three consecutive days, he sent out messengers to find a particular colonel who he was keen to meet "but whose apartment nobody in the place could indicate".

Following two fruitless days of hunting, Sir Charles "summoned a boy scout into my presence - a very small one - and commanded him to find that colonel and not to come back without him.

"In about 10 minutes' time, the door was flung open and in walked the scout, followed by one of the biggest sort of colonels. 'I did not know what I had done or where I was being taken', remarked the colonel, 'but the boy made it quite clear that he wasn't going to have any nonsense; so I thought it best to come quietly'."

Who worked in the Old War Office?

John Profumo photographed at his desk in the OId War Office in July 1960

Winston Churchill, held the position of secretary of state for war between 1919 and 1921 and was a frequent visitor during World War Two

T E Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia), was employed in the War Office Geographical Section M04 in October 1914

Lord Kitchener, secretary of state for war at the start of Wold War One, who was most famous for his "Your Country Needs You" campaign

John Profumo, his affair with 19-year-old Christine Keeler while he was secretary of state for war nearly toppled the government

Ian Fleming, would have visited the building as a naval intelligence officer working as a liaison with the Secret Intelligence Services during World War Two

At its peak, 22,000 staff had joined the War Office and, despite extra wooden huts being added on the roof - morbidly called the Zeppelin Terrace after the airborne attacks on the capital - employees were now based in 52 buildings across London, no doubt creating even more bureaucratic chaos.

The government department would again become a wartime base during World War Two, with Winston Churchill - the former secretary of state for war between 1919 and 1921 and now the wartime prime minister - regularly dropping into his old office for meetings with military chiefs to plan allied action.

Yet whether they were times of conflict or peace, there was always a rule that what happened in the War Office stayed strictly within the War Office.

"Although this was an absolutely splendid space, when you came into the building it was completely secret," says Mr Aslet.

The minister of war's office has now become a hotel suite, complete with numerous historical features

For secrecy was always going to be key for a place that had a doorway in the back known as "the spies entrance" and which became so synonymous with espionage it was an inspiration for Ian Fleming while writing his James Bond series.

In 1909, Britain's Secret Service Bureau was created during meetings at the Old War Office.

While the organisations that would develop into MI5 and MI6 would have their headquarters elsewhere, agents and spy chiefs would regularly visit for meetings, discussions and orders.

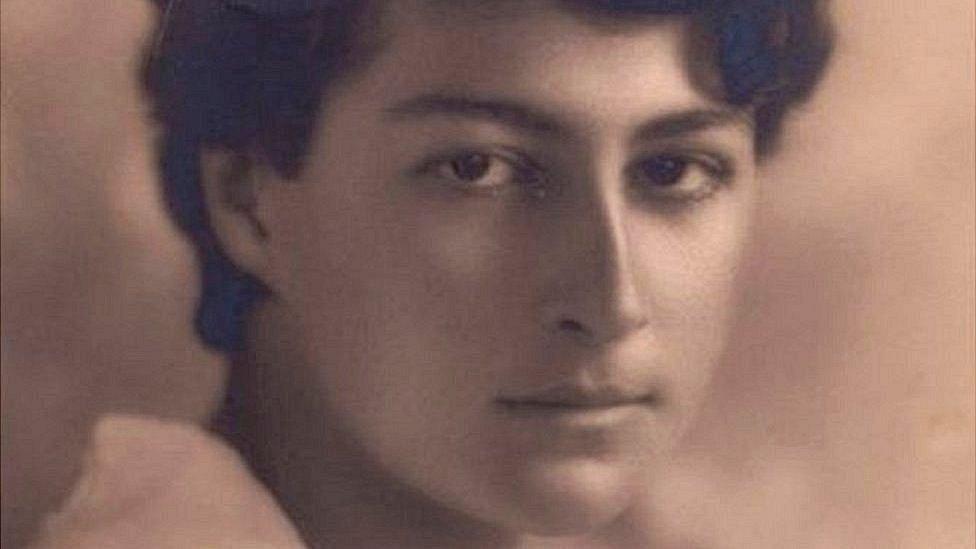

Among those who would have been partly controlled from the War Office was British World War Two spy Krystyna Skarbek - better known by her assumed wartime name Christine Granville.

The Old War Office has been used as MI6's base in five James Bond films, with this rooftop view featuring in 2012's Skyfall

Born the daughter of a Polish count, Granville found herself in London in Autumn 1939 and decided she wanted to do her bit, explains Clare Mulley, historian and author of The Spy Who Loved.

"She storms off to what's meant to be the secret headquarters of MI6 (next door to the Old War Office) and she doesn't so much volunteer as demand to be taken on, and they all kind of love her.

"She's part Jewish so they think she's absolutely nuts because her plan is to ski across the [Polish-German] border in minus 40 degrees to take information and bring back microfilm or whatever."

With Britain in dire need of intelligence about what was happening in the Nazi-occupied nation, Granville was deployed and over the months she carried out a number of missions crossing the Polish border.

On two occasions, she was caught by German soldiers, yet on each occasion her quick wits meant she managed to flee.

Christine Granville was Britain's longest-serving spy during World War Two

On one occasion, while being interrogated by the Gestapo at a time she was suffering from a hacking cough, "she bites her tongue so hard and so often that her mouth fills with blood.

"Then, when she coughs, it looks like she's coughing up blood, which is a symptom of tuberculosis. The Germans are terrified of this disease... so they throw her out," Ms Mulley says.

Eventually, she managed to get a microfilm back to Churchill that showed the Nazis were lining up their forces to invade the Soviet Union, leading the British war leader to declare to his daughter that Granville was his favourite spy.

Other missions took her to Egypt and the south of France, where she managed to persuade a German garrison to defect ahead of the D-Day landings.

By the end of the conflict, she was the UK's longest-serving World War Two special agent, male or female, as well as one of the most-achieving, according to Ms Mulley.

"Her great tool was her brain. She's so quick thinking in talking her ways out. She's amazing."

And it is Granville's success that has led to her and other famous women to having suites named after them within the new hotel, Raffles London at The OWO.

Corridors were wide enough so that messengers could deliver post around the building on bikes

Having no longer acted as the home of the Ministry of Defence since the 1960s - when the building gained the moniker the Old War Office - and with parts of the grand old building decaying, the government sold off the lease in 2014.

As work began to convert the regal office of power into a hotel, residences and nine restaurants, new discoveries were made within.

"We did a soft strip, which meant we removed 10,000 pieces of furniture. Try getting rid of 10,000 pieces of furniture - there's only so many charity shops," Mr Hull laughs.

Yet such work uncovered new historic features such as a fine mosaic, discovered under a carpet, showing the Old War Office logo, while other ornate details, windows and panelling were found behind additions made to the building in the 1970s.

"There was just this voyage of discovery as we began to strip out the building - there's a lot of history there," the architect says.

The kitchens at the Old War Office used to serve up more than 1,000 meals a day

Attention to detail during the conversion, which meant that even thousands of cobbles in the courtyard had to be individually numbered, has meant that the Old War Office's historic features have remained and a building that was once a fortress has become London's latest venue.

"It used to be this very, very secret place, which is all about planning wars, and now it's somewhere that anybody could come and it's about celebration," Mr Aslet says.

"It really couldn't be more different."

Additional reporting by Alice Bhandhukravi

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published18 September 2021

- Published5 April 2019

- Published9 September 2022

- Published11 October 2022