High rise heartbreak: The end of days at the Aylesbury estate

- Published

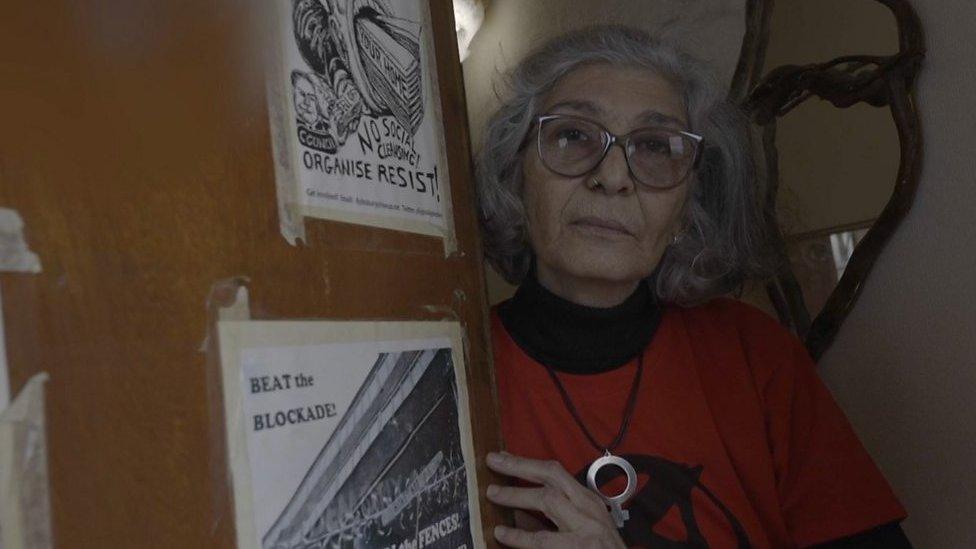

Aysen Dennis is lying on the only piece of furniture left in her lounge - her sofa. Tears run down her face.

She is waiting for a number of things - for a group of students invited to her flat to hear first-hand how planning decisions affect people.

She is waiting for the rest of her belongings - boxed up, labelled and in the corridor outside her home - to be taken by a removals team to their van on the street below.

And she is waiting until the very last minute before she has to leave her home forever.

Aysen Dennis, who lived on the Aylesbury Estate for 30 years, is distraught at the idea of leaving

The Aylesbury estate in south London was built between 1963 and 1977, when the principle of council houses was well and truly in vogue. It's estimated that at one point 11,000 lived on the Aylesbury.

It was a shining example of a future urban planners saw for London's population. Walkways in the sky linking together separate blocks to create a community with everything the residents needed.

Every home was kept warm by communal heating.

A woman pushes a pram at the estate in 1979, two years after the building was complete

Looking over low-rise blocks of flats and maisonettes during the topping-out ceremony of the Southwark Whites contract on the Aylesbury Estate in 1976

Pictured in 1969, the Aylesbury was the largest industrialised housing scheme ever undertaken by a London borough, providing homes for more than 7,000 people

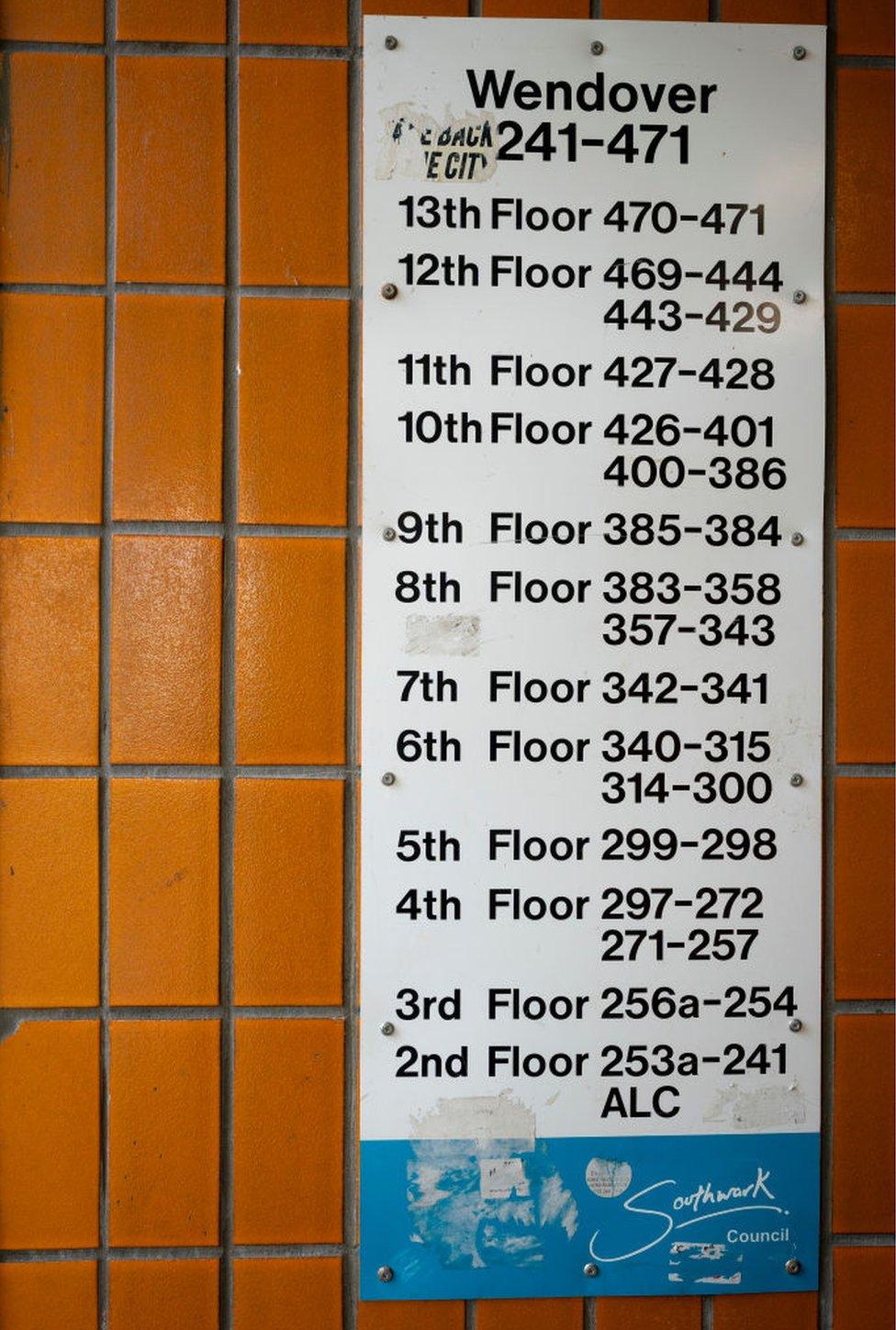

Ms Dennis lives on the eighth floor of the Wendover tower. It has been her home for 30 years - and for 24 of those years - since landlord Southwark Council first contacted the residents of the estate by putting leaflets through the doors - she has been campaigning to keep it.

I'd first met Ms Dennis in May. I'd read about her on a community website, then looked up the campaign she was running to save the estate she lived on.

She welcomed me in to talk about her fight not only to stay in her own council home, but for the principle of local authorities building more council homes for working-class Londoners, many of whom are priced out of any other form of home ownership or security of tenure in the capital.

She said: "It was so special when me and my sister got the place. We made it our home - it was a lovely home …welcoming."

Her sister died in 2019 of a brain haemorrhage, so for the past three years she's been living here alone.

Demolition work takes place on the huge Aylesbury council estate in Southwark, home to 7,500 people, in 2010

Ms Dennis - and until her death three years ago, her sister - lived on the eighth floor of Wendover tower

The reality of the Aylesbury turned out somewhat differently from the ideals of the planners.

The estate, like many in Britain built at the same time, became riddled with problems. From bad tenants and drug dealers to muggings and vandalism. Tony Blair famously used the Aylesbury as a backdrop for his first public appearance after becoming prime minister. He talked of "sink estates" as the residents looked on at the media circus that had descended on them.

Those residents are now long gone. Ms Dennis's neighbours too. The doors to their flats are sealed with heavy duty steel, each a representative of someone - a family maybe - who took offers of homes elsewhere in the borough. Who were displaced from the neighbourhood where they raised children and formed their lives.

Tony Blair used the Aylesbury estate as a background to some of his political campaigns

Aysen Dennis, pictured in 2016, had already been campaigning against the regeneration of the estate for 16 years when this photograph was taken

The Aylesbury estate in Walworth has been subject to a phased regeneration process since 2005

Of the Wendover tower's 240 flats, just 16 homes remain occupied. When Ms Dennis closes her door for the final time today, it'll become 15.

Some of those 15 households will join her in the new building she's moving to.

I ask her about her new home. We can see where she'll be living from later today from her lounge window. She calls it "the place".

"I had to go to the place in the end. I had no choice.

"The council gave me everything I asked for. It's on a high floor. There's lots of light. I can see the park.

"But it's not my home."

A woman with a pushchair at the estate in 1979

A row of gardens on the Aylesbury estate in 1978

It could be easy to think she's ungrateful. A new flat in what is basically central London. Many living in the capital can only dream of being in this position.

But for her there was nothing wrong with the home she's leaving and that is the crux of her issue. When the final resident goes, the building will be torn down.

Southwark Council says there will be more than 4,200 new homes when the regeneration of the Aylesbury estate is complete, up from the 2,758 homes it had originally.

It says the mix of tenure will also change - from 82% council housing and 18% private, to 50% private and 50% affordable. Of those affordable homes, 75% will be social rent or council housing, and 25% shared ownership.

The mixed-tenure housing will cross-subsidise the development, with the sale of private homes paying for the rented homes as well as the new community, energy and public infrastructure.

The council also points out it is a branch of local government - not a business seeking to make profit.

Ms Dennis was too upset to clearly articulate her thoughts about the regeneration of the estate

The students have arrived - about 15 of them.

Ms Dennis wants them to understand how their decisions in the future, whether made in planning offices or council halls, have a huge impact on real life.

But she's too upset to put her thoughts into words. She's unable to stay composed enough to explain her feelings.

Less than 10 minutes later, the students are gone.

In July, Ms Dennis addressed other social housing campaigners from Southwark to call for an end to the demolition of council housing

Social housing campaigners from Southwark march alongside the remaining section of the Aylesbury estate to call for an end to the demolition of council housing

As I get ready to leave the flat for the last time, I ask Ms Dennis what this move means for her future.

"I am still going to be fighting. I am fighting the ideology of building more council houses, and keeping the existing ones maintained and refurbished.

"That fight is not going to end here.

"But before I go, I want to spend some time in this house by myself. To say my own goodbye to my memories. And then I'm going to take the keys to my housing officer and finish 30 years of my life.

"It's been ripped off me - that's how I see it."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, external, X, external and Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hello.bbclondon@bbc.co.uk

Related topics

- Published18 January 2023

- Published20 February 2014

- Published14 April 2023