The gaiety and grimness of 1683's The Great Frost

- Published

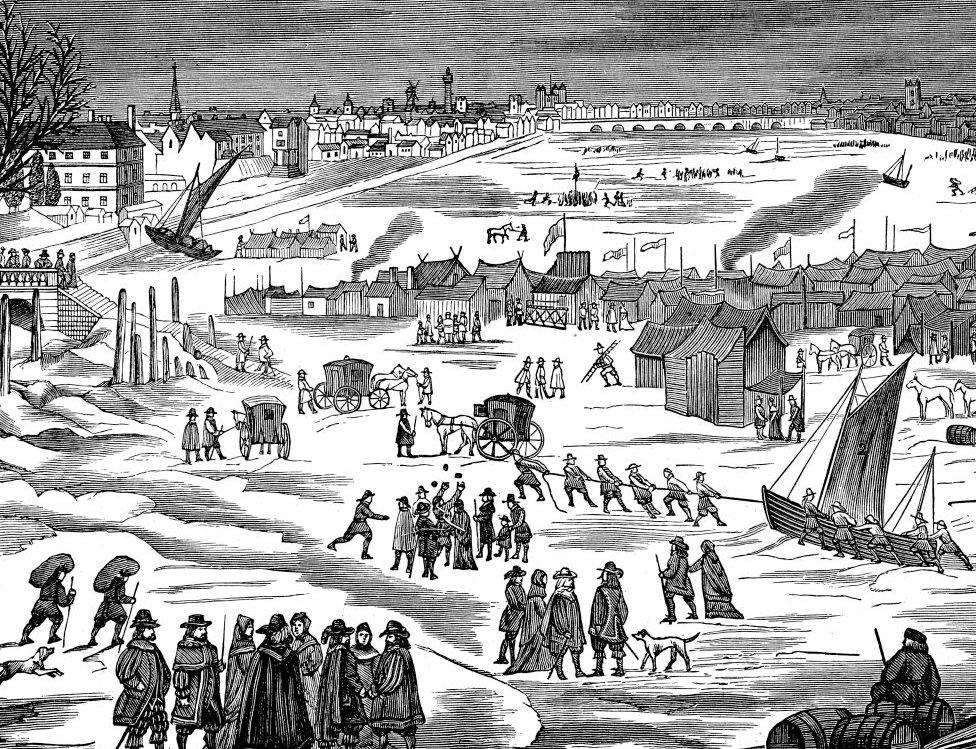

The River Thames viewed, probably, from Old Swan Stairs looking east with old London Bridge in the middle distance

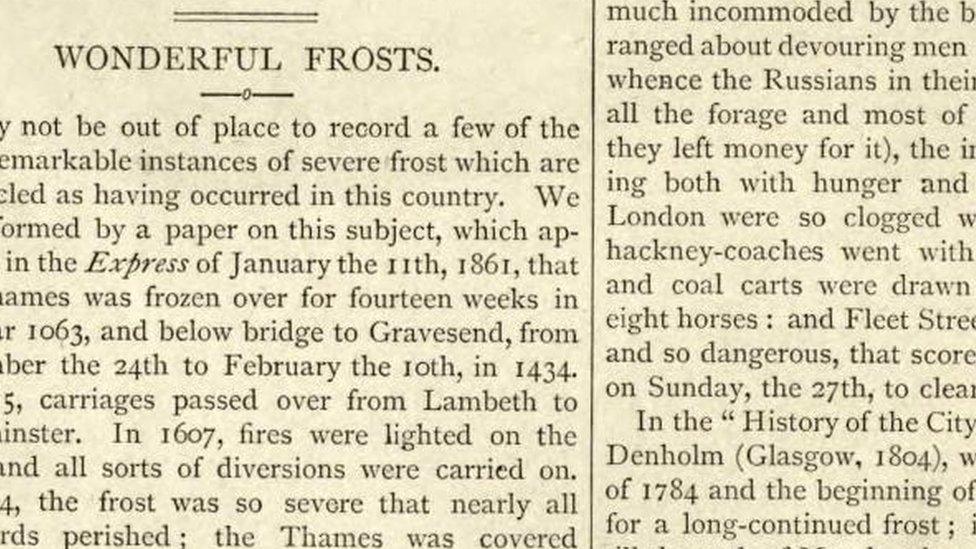

Nearly three-and-a-half centuries ago, the country was in the grip of a winter so cold it became known as The Great Frost. It is considered the worst freeze England has ever experienced.

Exact temperatures were not recorded in the 17th Century, but the records of a Dr John Downes, a physician to Christ's Hospital in London, reveal daily temperatures in the region of -4°C indoors and -12°C out.

The lowest reported was -30°C.

Families froze and starved, the price of food and fuel soared, cattle and deer died where they stood.

Journalist Charles Mackay wrote "it was so cold the trunks of trees exploded with cracks as loud as the firing of musketry".

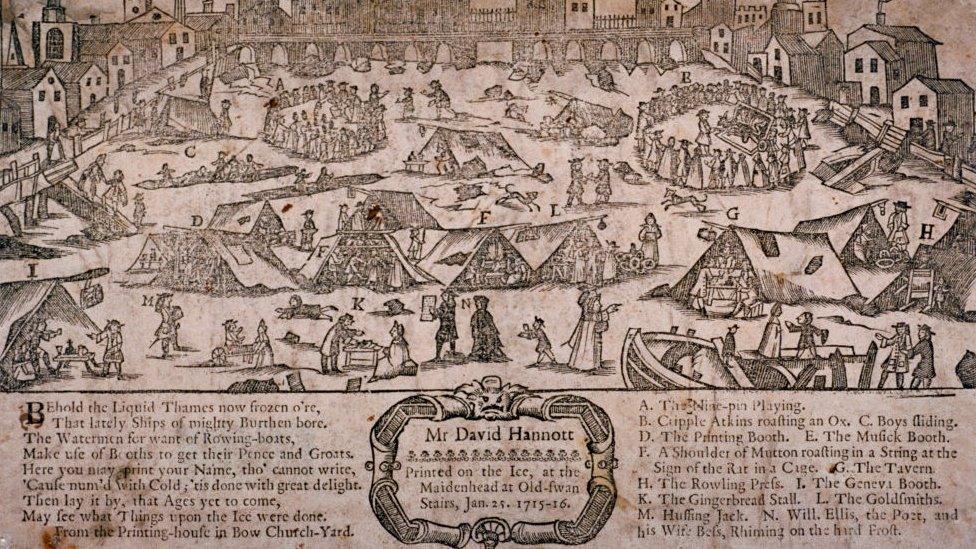

A depiction of the 1683-4 frost fair

Diarist John Evelyn asserted that "crows' feet were frozen to their prey", a monk wrote "we have seen soup which has accidentally spilled while being stirred, freezing at one side while the other still steams" and The World of Wonders (an 1896 book aiming to be "a record of things wonderful in nature, science and art") said "the frost was so severe that nearly all the birds perished".

It was even reported by Mackay "that some skait-sliders upon one of those large icy plains [of Europe] were unawares driven to sea, and arrived living, though almost perished with cold and hunger, upon the sea coast of Essex".

"The Humorous Diversion of Sliding on the Ice" c1745. On the right a young man has slipped and hit his head where blood pours from the wound

The River Thames was topped with a foot of solid ice and remained frozen for two months, meaning goods could not be transported by boat. Watermen and others who made their livings from the river faced a dismal end.

There was even speculation, printed on a news sheet now at the British Museum, that it was down to "the scourging hand of an offended God".

The author said, "I loudly call for humility and amendment of life, lest a worse judgment fall upon us."

Ice golf on the Thames

The Thames freeze started slowly. From mid-November 1683 there was a series of mild frosts and small thaws. Mid-December saw the real frost begin. The centre stream remained flowing, albeit with increasingly large deposits of ice, until the Thames tideway - the part of the river and its estuary subjected to tides - was captured from bank to bank.

It was soon discovered the ice was solid enough to bear weight - in the first week of January, a coach and six horses was driven across it for a wager.

Frost Fair on the Thames, with Old London Bridge in the distance

As the temperatures fell and the raw air tried to flay the flesh from the bones, Londoners erected rows of booths and stalls - creating a frost fair.

Frost fairs had been held on the Thames before - but not like this one. Traders had previously set up shop on the ice, and travellers had trudged across. The 1683 fair was the first one to become an attraction in its own right.

Flyers were printed, and advertisements taken out in news sheets, which promised illustrated maps and "alphabetical explanations of the most remarkable figures curiously engraved on a large sheet of paper."

The 1896 work The World of Wonders refers to the 1683 frost fair

There was at last a chance for the bargemen and sailors frozen out of work to earn money by guiding sightseers out onto the ice. Others fitted their small boats with runners, turning them into sledges, and offered rides along the frozen river.

John Evelyn described the bull-baiting, races, puppet shows and many food and drink stalls (an entire ox was roasted on the ice near Whitehall) in his diary as "a bacchanalian triumph or carnival on the water."

Souvenirs were hastily produced, ranging from engraved silver spoons to tickets printed from presses that had been hauled onto the ice.

![Mr. John Forde, the first dated January 30th 1683 [i.e. 1684]](https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/ace/standard/976/cpsprodpb/4A31/production/_132339981_32349a8d-62e8-4f05-bc86-87085bbe21f2.jpg)

Commemorative ticket printed on the ice

A fellow diarist, who rejoiced in the name of Narcissus Luttrell, recorded in his journal on 4 February 1684, "that there were three or four printing houses on the ice" when he visited.

He noted that the owners of the printing presses made good money - but the poorest people "were miserable".

The watermen who turned their hands to on-ice transportation now had to compete with their land-dwelling contemporaries, who could use the ice as an extension of their businesses. There were few river workers who managed to make a good living by pushing a boat on runners when horse-drawn hackney coaches were available.

Winters in Britain were often particularly cold in the 17th and 18th centuries, a period known as the Little Ice Age

The watermen had even planned to petition the Court of Aldermen to ban the coaches on the river - but the day the petition was to be presented, 5 February, the thaw set in.

There were more fairs in the years that followed, but none so large or long lasting.

The last, in 1814, only lasted for four days. Since then, the Thames tideway has never frozen over.

Follow BBC London on Facebook, external, Twitter , externaland Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to hellobbclondon@bbc.co.uk, external

Related topics

- Published5 July 2022

- Published1 March 2018