How Colman's mustard became synonymous with Norwich

- Published

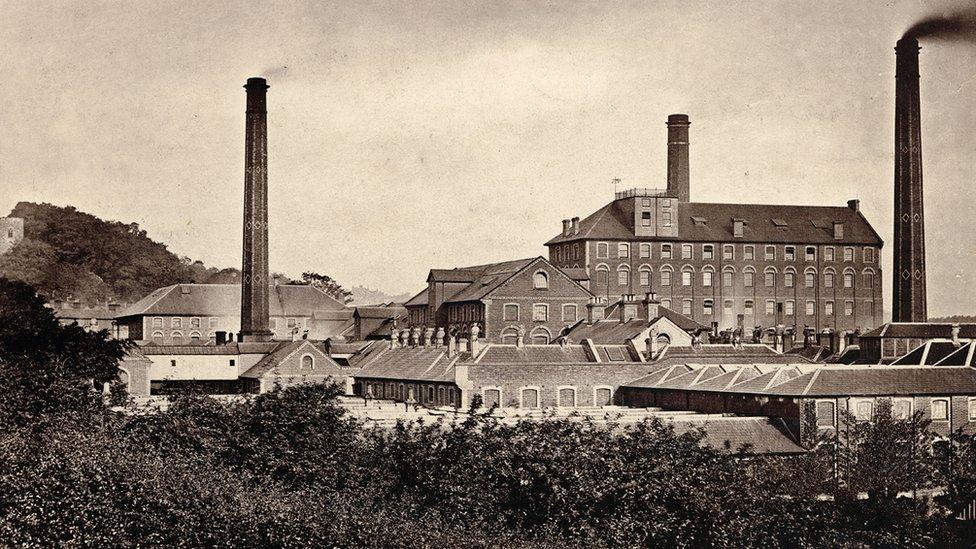

Colman's has been based in Norwich for 160 years

Colman's is one of Britain's best-known brands, but the decision to close its Norwich factory threatens to end 160 years of manufacture in the city famed for its mustard.

Its products are a dinner table staple, with every jar, packet and bottle bearing the words "Colman's of Norwich".

But that slogan could soon ring very hollow. Owner Unilever has announced it will close its Norwich factory next year and switch production to Burton-on-Trent and Germany.

The news saddened actor and entertainer Stephen Fry, who went to school in the city and is a former director of Norwich City FC.

"Norwich without #Colmans?" he tweeted.

"Take the Tower from London, the RSC from Stratford and the potteries from Stoke, but leave our mustard in the Fine City. A sad day. A sad day."

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

Unilever says it will protect the historic link between Norwich and Colman's by retaining production and milling of mustard powder in a new facility in the area.

It was a concession won in part by lobbying from the New Anglia Local Enterprise Partnership (LEP).

"Colman's is synonymous with Norwich, in the same way that Worcestershire sauce is with Worcester, and Bass beer is with Burton," said its chief executive Chris Starkie.

"The Colman's name is seared into the consciousness of people who live in the city and those further afield who, through its advertising, recognise the brand.

"It links Norwich to a wider audience."

In 1858, Colman's moved to its current site at Carrow

The Norwich Society says Norwich and Colman's "go together"

Colman's no longer makes just mustard and has a large roster of sauces and condiments sold across the world.

The closure of its factory means the loss of at least 50 jobs and is another blow for the city - last month, drinks manufacturer Britvic, which shares Colman's sprawling Carrow Works site, announced it was leaving, with the loss of 242 jobs.

Mr Starkie said the impact of the Colman's closure on the city would be "far more psychological than economical".

But he added: "That doesn't in any way lessen the impact on the lives of the workers losing their jobs, and our priority is to support them through this difficult process."

Paul Burall, vice-chairman of The Norwich Society, said: "Norwich and Colman's - and Colman's and Norwich - go together.

"It's part of the history of Norwich, and people think of Colman's as part of the family."

It is a feeling that stems largely from the attitude of the company's founding fathers. For generations of staff, Colman's was far more than just an employer.

The move to Carrow Works meant mustard seed could easily be brought in by train

Founded in 1814 by Jeremiah Colman, the firm had a cradle-to-grave ethos, providing education, housing, healthcare and leisure for workers and their families.

"Old" Jeremiah died in 1851, followed three years later by James, his nephew, who he adopted as his son and made his business partner.

James's son, Jeremiah James Colman, took over and proved to be a brilliant innovator whose masterstrokes included creating Colman's famous bull's head trademark in 1855 and moving from nearby Stoke Holy Cross to the Carrow enclave, which was bordered by beneficial railway and river links.

The young entrepreneur also identified a ready-made workforce in the city - cloth workers made redundant by the industry's exodus to northern mills.

Reaction to the factory closure was mixed

He followed his great uncle's example in educating employees' children, building a school on Carrow Hill in 1864 years before education was compulsory, and provided sick benefits, and savings and pensions schemes.

Colman's also employed one of the first workplace nurses, built coffins for workers and their families, and rented and built houses for workers and pensioners.

Many were in neighbouring Lakenham and Trowse, and some of the terraces were said to have had mustard-coloured front doors.

The school built by Colman's in 1864 still stands on Norwich's Carrow Hill

The doors of some rows of terraces, built by Colman's, were said to have been painted mustard yellow

Thelma Blower, 91, was the third of four generations to work at Colman's. Her grandparents started there before the turn of the 1900s, joining a workforce of about 3,000.

They were followed by both Mrs Blower's parents and later, three of her four children - including Valerie Colby, who joined straight from school, aged 15.

"I was absolutely proud of working there - most people were," said Mrs Blower, who joined the firm during World War Two.

"The money was not big in the wartime, but Colman's was a family."

One day she was one of six girls asked to stay on for an extra hour to prepare a shipment and in doing so, survived a German raid, sheltering in tunnels beneath the site.

"Our manager came up and thanked us for staying behind but said he had some sad news," she said.

"He then said, 'It is God's will and fate I asked you to stay on - five women on Carrow Hill have been killed by a German plane'.

"They were all from the mustard department."

Working an extra hour at Colman's during a German bombing raid saved Thelma Blower's life

Peter Webber's father Roy and grandfather Charles both worked at the plant

Peter Webber, 69, was at Carrow Works for 30 years until 2008, following in his grandfather's and father's footsteps.

His semi-detached house in nearby Trowse had been built for the supervisory ranks - a step up from the terraces ordinary workers lived in.

"I was a tradesman, but I made more money a week on the lines than I did as an upholsterer," he said.

"I used to think how lucky I was to work at a place with a canteen, medical centre, physiotherapist and chiropodist - it was 50p a foot.

"If you had to go to hospital they had their own ambulance, but that was the type of company it was."

Peter Webber was told to leave the artwork to his son

Mr Webber's grandfather Charles spent his entire working life at Colman's, receiving a painting of an Italian castle as a long-service award.

"He left it to my father, my father left it to me and he told me I have to leave it to my son," said Mr Webber.

"I'm absolutely devastated to think about the site closing because I shut my eyes and think back and it's choking. It's been a big part of my life."

The Colman's legacy

Jeremiah James Colman was the third family member to run the firm

The company was founded in 1814 by Jeremiah Colman at Stoke Holy Cross, near Norwich

In 1858, it moved to its current site at Carrow

Colman's was granted a royal warrant in 1866

In 1903 it bought rival firm Keen Robinson and Co whose mustard was a household name, hence the phrase "keen as mustard"

The firm merged with Reckitt and Sons in 1913 to become Reckitt and Colman

The Colman's Mustard Shop and Museum opened in Norwich's Royal Arcade in 1973

In 1995 Colman's became part of Unilever's Van Den Bergh Foods

The Mustard Shop - by now a social enterprise - closed in 2016 when its lease ended

- Published3 October 2017