Hemsby erosion: 'I knew it would happen but not this quickly'

- Published

While it remains a popular tourist destination, Hemsby, including its lifeboat station at "the gap", has become equally well known for its fast-disappearing coastline

There's not much retired fisherman Kenny Chaney doesn't know about the Norfolk village of Hemsby. Despite working from Hemsby's beach for 52 years, the rate of coastal erosion has surprised even him.

An avid photographer and collector of postcards, Mr Chaney has built up a personal pictorial archive of Hemsby.

His collection charts not just his own life in the village, currently home to about 3,200 people, but also its gradual swallowing up by the sea.

He holds one photograph showing a vast, golden beach with thousands of holidaymakers enjoying a sunny day there.

"When I started fishing back in 1957, it was a really bustling holiday place - you couldn't move down at the beach," the 77-year-old says. "It would be absolutely packed.

"I reckon there were between 10,000 and 12,000 people on that beach on a busy day, easily."

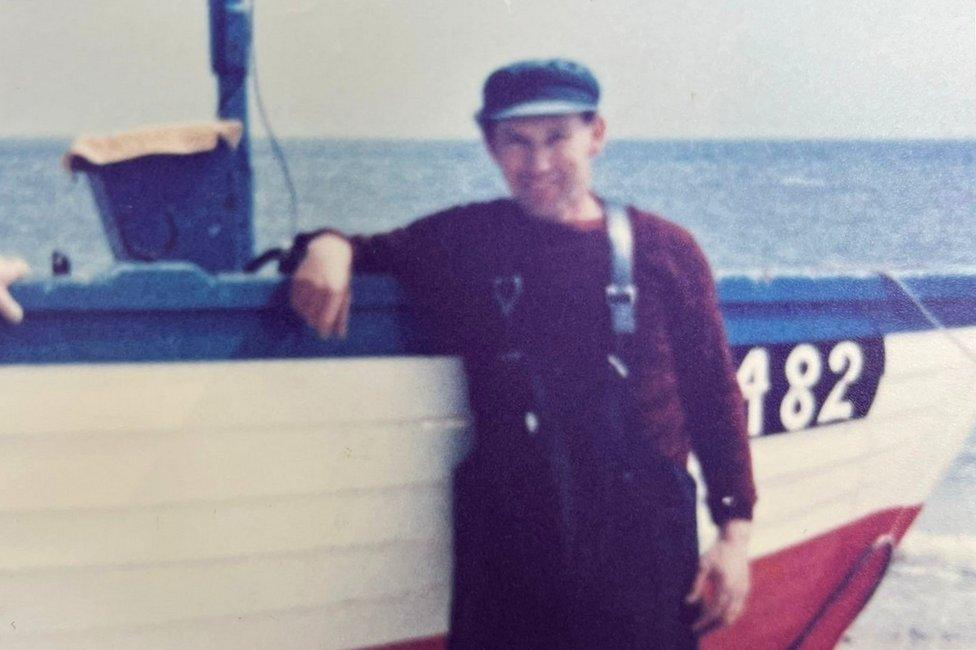

Retired fisherman Kenny Chaney worked off Hemsby beach for 52 years

While it remains a popular tourist destination, Hemsby has become equally well known for its fast-disappearing coastline.

The beach, to the north of Great Yarmouth and Caister, was closed earlier this year when high tides claimed metres of sand from the access point known as "the gap".

Five homes on The Marrams were demolished before they collapsed into the sea.

Kenny Chaney's family has a history of making a living from the sea, stretching back to the 18th Century

"I've seen most of the things which have gone on at Hemsby beach over the years," Mr Chaney says. "I've lived here all my life and I wouldn't have thought it would possibly have eroded so much and as quickly as it has done.

"I've seen all the big tides and all that. The problem is getting bigger all the time."

He says the beach level needs to be raised and then properly protected by a full stretch of granite rock defences.

"We should have some fishtail groynes in here before the rocks were put in - to build the height of the beach back up to how it was. It is 12ft [3.6m] to 14ft [4.2m] lower than it was in 2013."

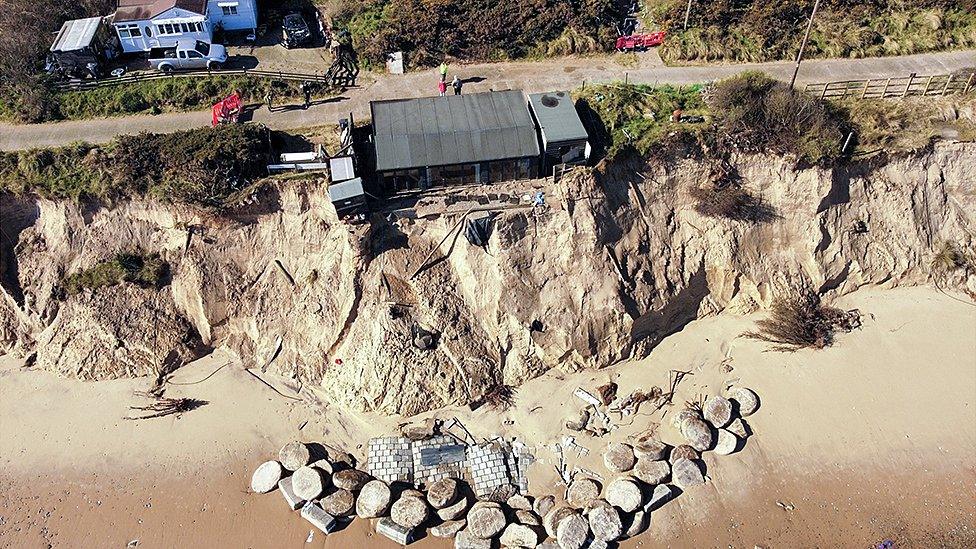

It has suffered considerable coastal erosion since this photo was taken in the 1970s - the pillbox seen above is now in the sea

In March, an 80m (262ft) rock revetment was installed as a temporary solution, created from 2,000 tonnes of Norwegian granite.

"We have now got a few rocks on the beach," Mr Chaney says. "It is like putting a barrel-load where you want a lorry load."

"And if you don't do the lot, you leave a weak spot and it [the sea] will find it."

Kenny Chaney became a fisherman in 1957 and worked with his uncle before working alone for 30 years

Experts say the East of England has a soft coastline and has been eroding for at least 5,000 years.

Describing the loss of people's homes at Hemsby, Mr Chaney says: "It is devastating for them. It makes you despair, really.

"At the beginning there wasn't anybody who lived on The Marrams. I could see what was going to happen to this beach, but I didn't think it was going to happen as quick as it did."

One of those to have benefitted from Mr Chaney's knowledge is former solder Lance Martin, whose home has twice been rolled back away from the edge of the cliffs.

"Hemsby is full of characters from all walks of life," says Mr Martin, who retired in 2017. "I love it."

"He knows all about the tides, the surges and the wind," Mr Martin says.

He describes an encounter with Mr Chaney a few years ago when he was trying to find old rock defences on the beach to defend the ground beneath his home.

Lance Martin's house was twice pulled away from the eroded cliff

"I was looking for the blocks on the beach and he came along and said, 'what are you looking for, boy?' as they do in Norfolk," he says.

"I said I am looking for where the slabs are buried, the big blocks.

"He said 'oh, they're about 27 paces away from the base of the dunes or they were'."

Sure enough the rocks were beneath the sand exactly where Mr Chaney had said.

"He also told me that when I do put the blocks around the base of my house to make sure I'd got the best protection at the north-easterly end, because that's where the wind and tide come in from.

"I did, and as you can see I've got a big piece of land jutting out here where everybody else's is flat."

Lance Martin's property, on the south side of the Hemsby gap, is vulnerable on the cliff edge

"Hemsby is full of characters from all walks of life," says Mr Martin, who retired in 2017. " I love it."

He paid the asking price for his Hemsby home six years ago and moved in.

"It was an idyllic little cottage dwelling and I couldn't actually see the sea from my property. I actually had to stand on the roof because the dunes were that high."

He had an environmental impact study done for the property which said the rate of erosion was about 1m (3ft) a year.

"That would have seen my lifetime out," he says.

During the high tide in March, Mr Martin was once again forced to roll back his home from the cliff edge.

As for Mr Chaney, he says he admires the "vision" and efforts of people like Mr Martin.

"You can say that they were a little bit naïve," says Mr Chaney. "But I've lived here all my life and I wouldn't have thought it would possibly have eroded so much and as quickly as it has done."

The government says it has allocated £36m to coastal communities to help them adapt to a changing climate.

Plans for a permanent defence stretching 0.8 miles (1.3km) have been granted a licence by the Marine Management Organisation - but Great Yarmouth Borough Council needs to find £15m to carry out the work.

Life on the Edge is available on BBC iPlayer.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published7 April 2023

- Published26 March 2023

- Published17 March 2023

- Published15 March 2023