Will the crisp bags of today still be washing ashore in 60 years' time?

- Published

Tash Jones, of Fairfields Farm Crisps, near Colchester in Essex, says she is pleased the spotlight has fallen on crisp and snack manufacturers to improve their packaging

Wry smiles and sense of nostalgia aside, the appearance of crisp packets from the 1960s on a Norfolk beach is a potent reminder of the longevity of single use plastics. Can anything be done to prevent today's crisp packets returning to our shores 60 years from now?

Chris Turner was staying at his holiday home in Scratby, near Great Yarmouth, when he started to find decades-old litter on the beach.

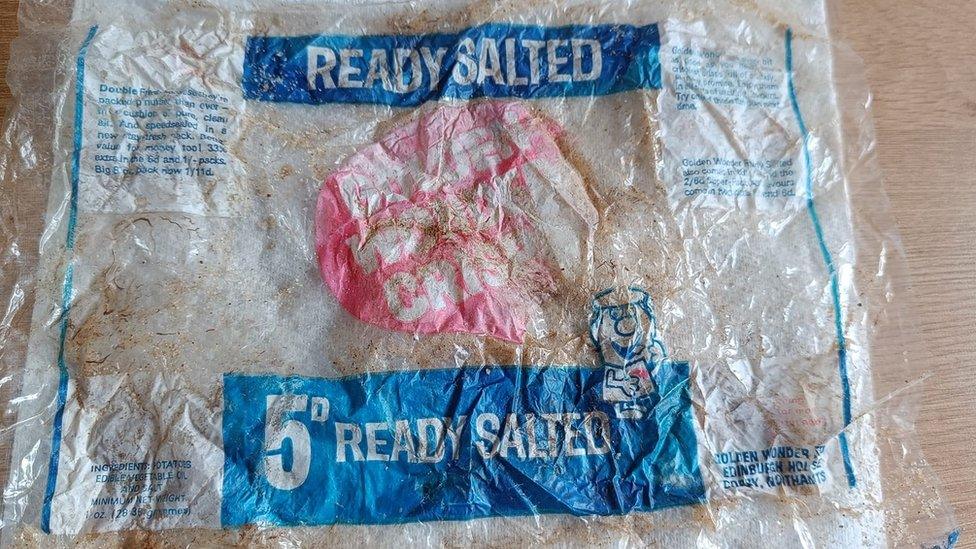

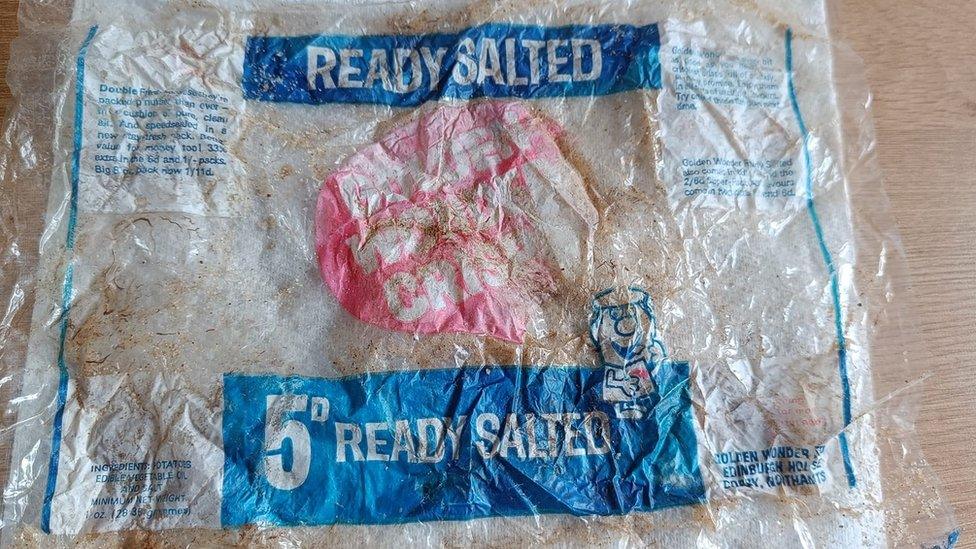

His discoveries include pre-decimalisation packets of Golden Wonder crisps, marked with a price of 5d, and 2d Spangles sweets.

The Golden Wonder crisp packet is almost certainly from the late 1960s

According to Statista, the UK devoured 8.3bn packets of crisps in 2017, external. By 2030, the consumer data firm expects that number to rise more than 30% to 11.1bn a year.

The volume of single use crisp packets has both environmental experts and the crisp makers themselves concerned.

Tash Jones, of Fairfields Farm Crisps, near Colchester in Essex, said she found Mr Turner's discoveries at Scratby very "disheartening".

"Packaging is a difficult one and I don't think anybody has quite got there yet," she said.

Fairfields, she said, was committed to finding ever more sustainable forms of packaging for its crisps.

The company has tried a number of different packaging types in recent years, including a single ply wrapper which was found to reduce the shelf life too much to be economically viable.

Ms Jones said while many crisp packets are recyclable they are not recycled, partly because consumers have to take their flexible plastics to special facilities rather than have them collected at the kerbside

Its move from a three-ply packet to a two-ply bag using thinner film from a net-zero carbon packaging producer, however, has worked well, said Ms Jones.

What about compostable bags?

"It is not a never," said Ms Jones. "But a lot of local authorities will reject compostable packaging."

The biggest issue, she said, was that while many crisp packets are recyclable, they are not actually recycled because many people will put bags in the bin rather than take them to a dedicated flexible plastic recycling facility.

Anatomy of a crisp packet

Laura Scudder created in the first sealed packet of crisps in the US in the 1920s, external using waxed paper bags

However, such packaging was not airtight, which led to crisp makers using plastic bags instead

In the 1950s and 1960s, crisp packets were made from single-layer of plastic, often with a transparent section so the buyer could see the crisps inside

Today's crisp packets often have a number of layers and are usually made from polypropylene or polyethylene with an aluminium coating

The environmental charity WRAP agrees.

"There is still change that needs to take place for widespread roll-out of recycling collections at kerbside for plastic bags and wrappings," a spokesperson for WRAP said. "The infrastructure to recycle this type material at scale, is not universally available.

"Every form of packaging leaves an environmental footprint, and packaging innovations must reduce these to be more sustainable."

However, the organisation said consumers needed to do their bit too by taking their crisp packets and similar wrappers to recycling facilities at supermarkets across the UK.

The charity said it understood the difficulties some people faced in recycling plastic wrapping but warned it was "a critical step in the pathway to building the infrastructure at scale".

It said it would "continue to work with industry partners to prepare for kerbside collections of plastic bags and wrapping".

The biggest crisp company in the UK is Walkers, which is owned by PepsiCo.

"We plan to eliminate virgin fossil-based plastic in all crisp and snack bags by using 100% recycled or renewable content in all packets by 2030," a spokesperson said.

In the meantime, the company said it was finding ways to cut the amount of plastics used in its packaging and encouraging customers to recycle packets.

It was four years before Sean Mason, right, and Mark Green could get their crisps on the market

The recycling issue is entirely bypassed by the Herefordshire-based company Two Farmers, which sells crisps in compostable packets.

Co-founder Sean Mason said his packaging is made of cellulose and uses plant-based inks and glue. An extremely thin layer of aluminium is applied to the inside of the cellulose wrapper to keep the crisps fresh.

"The aluminium sprayed on the film is less than you would find in the soil and there is zero plastic," he said.

The firm's bags will break down in a typical domestic compost set-up within 25 to 35 weeks.

A packet for a standard 40g bag is about 1.6p. A compostable Two Farmers bag costs 12.5p

So why aren't all companies going down the compostable route?

The first reason is price.

A packet for a standard 40g bag costs independent crisp makers about 1.6p. A compostable Two Farmers bag costs 12.5p.

"We launched with it and gave consumers the choice - they knew we were more expensive from day one."

For other makers suddenly to increase their packet price by 11p to cover the compostable packaging cost could kill their business, said Mr Mason.

The second issue is shelf-life.

A typical plastic and foil bag has a shelf life of six or more months while a cellulose packet is about 4.5 months, said Mr Mason.

Plastic kills fish and sea animals and takes hundreds of years to break down into less harmful materials.

A selection of the crisp packets found by Mr Turner at Scratby

Two Farmers' cellulose packets, on the other hand "completely break down in water", the end product resembling a slimy goo.

If they were eaten by a sea animal the bags, Mr Mason said, would "break down in their digestive tract and pass safely through".

"We don't want our bags littered anywhere, but if they were dropped at sea you wouldn't find our bags coming to shore from the water in a year's time never mind in 60," he said.

Find BBC News: East of England on Facebook, external, Instagram, external and Twitter, external. If you have a story suggestion email eastofenglandnews@bbc.co.uk, external

- Published16 May 2023

- Published27 October 2022