The lifeline for dads coping with the loss of a child

- Published

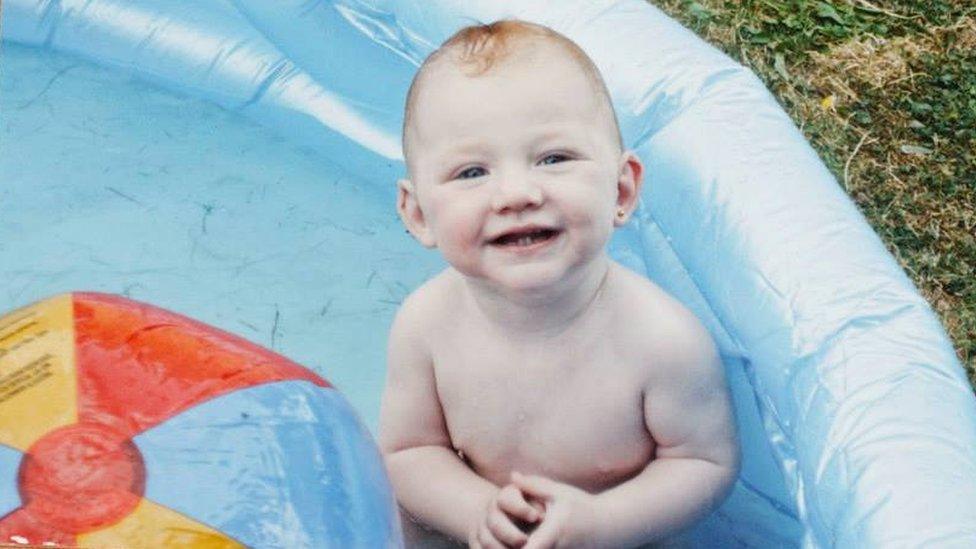

Paul Scully-Sloan's son TJ inspired the online support group Daddys with Angels

When toddler TJ Scully-Sloan died suddenly, his mum and siblings were offered support and a shoulder to cry on. But his dad was asked how he was feeling just once, by an undertaker. The experience led to him setting up a group to help fathers address a question no-one wants to have to answer - how do you cope after the death of a child?

Friday 19 November 2010 was like any other night in the Scully-Sloan household. After a normal, busy, bedtime routine, TJ was tucked into bed by his mum, Helen. It was like any other night, except the little boy didn't wake up.

Six years on, Paul Scully-Sloan, 49, still struggles with the words.

"At a quarter-past five the next morning, his two-year-old sister Miya-May was up shouting, running round, banging doors. His four year-old brother Calum was standing in the middle of the floor, like a rabbit in the headlights.

"Helen looked at TJ who wasn't moving with all this noise. She shouts for me and I can tell there's something wrong.

"I said 'give me your phone - take the kids downstairs - turn on the television, stand by the front door'. I picked TJ up from the bed, he's cold and he's blue, put him on the floor, started to try to resuscitate him and at the same time ringing the ambulance.

Paul Scully-Sloan set up Daddys with Angels to support other fathers facing the loss of a child

"What seemed like forever, but it was like 20 minutes, a paramedic came in and told me there was nothing I could do."

TJ - whose full name was Travers James - had died in his sleep of natural causes. Tests found he'd had inflamed tonsils and a severe flu-like virus.

In a period of indescribable grief, Mr Scully-Sloan felt alone.

He "didn't fit the criteria" for many established child loss charities. His son was too old for Mr Scully-Sloan to benefit from the help of miscarriage or stillbirth organisations. He felt fathers needed somewhere to unload.

In the front room of a house in Northampton, Daddys With Angels (DWA) was born.

"There wasn't a place for dads where they felt welcome," he said. "There wasn't a place to say what they needed or what they wanted to say, to be honest about it, without the fear of being judged. There were groups for men - but run by women.

"You're supposed to be strong, to crack on with it.

"I had some understanding of child loss through my work, but not of the impact. Everything changes," he said.

Paul Scully-Sloan's son TJ, who died in 2010

"We talk about the 'new normal'. Waking up knowing your child is not there. But life is not going to go back to the way it was, things are going to change and you're going to view things differently."

Increasingly, bereaved fathers are turning to groups such as Mr Scully-Sloan's.

The Lullaby Trust, which supports families after a sudden infant death, offers a befriending service to extended family members, which has seen great demand from dads.

"We have a policy here that we always ask about the other parent after a child's death, and our befriender scheme is well used by dads," said director of services, Jenny Ward.

"Different groups need different means to reach that support and the way people access it is changing all the time."

Mr Scully-Sloan, who is separated from TJ's mother, says the stress of losing a child can have a devastating effect on the family unit.

"In order to be good for your partner you need to be in a good place yourself. The biggest problem with child loss and couples is that they don't tell each other how they're feeling. They fear they'll upset them even more. What they really want to say is: 'I hurt too'.

"As soon as they can say that - it's almost like a relief. The other person in that relationship is feeling the same."

At the time of his son's death, Mr Scully-Sloan was also desperately ill with liver disease and awaiting a transplant.

"We had his funeral four days before Christmas," he said.

Knitted cots have been donated from across the country

"People were coming to the door - people we hadn't seen for ages - bringing flowers and saying 'how's Helen?' - telling me I looked yellow. People were phoning up to speak to Helen, even when we were at the hospital, people were asking 'how's Helen, how's the kids?'

"The only person who asked me, between TJ dying and the funeral, was the undertaker. She looked after TJ so well, asking what I wanted him to wear - he had his ear pierced - she even managed to put his little earring back in for him. She did that for us - the little things.

"At the funeral I said I wanted to carry his coffin. It was cornflower blue. When I had to take it out of the hearse I couldn't pick it up - nobody said 'how are you - do you need any help?' - I had to put it down and admit I wasn't strong enough."

This, said Mr Scully-Sloan, is why he wants to help other bereaved dads.

"Fathers need to know someone has walked in their shoes," he said.

"I know what it's like to sit alone with the TV off and the lights off, just sitting there thinking.

"Men want to fix things; they can't fix child loss. The next best thing is to talk about it."

Daddys With Angels

Knitted bootees donated to Daddys With Angels for stillborn babies

Daddys With Angels now has almost 1,000 members, six trustees and four support workers, helping anyone who has lost a child at any age.

Mr Scully-Sloan describes it as a "safe place" for fathers to "rant or chat" or get support and advice.

DWA has twice won Best UK Support Organisation at the Butterfly Awards, which celebrates the work of parents and professionals at the front line of bereavement.

The aim now is to establish a DWA helpline and set up group meetings around the country.

An appeal for volunteers to knit cots, wraps and hats for still-born babies saw a big response and items now fill Mr Scully-Sloan's living room.

He has already delivered dozens to bereavement midwives at the Liverpool Women's Hospital, his local unit at Northampton General and to funeral homes.

Rachael Moss, a bereavement support midwife at Northampton General Hospital, said the little cots are a lifeline.

"The items brought in are so individual and so appreciated, you can see how much care and compassion has gone into making them - it's amazing.

"Families know they are not on their own. To know that there is someone else out there, another means of support, means everything."