Nottingham: The city where they keep finding caves

- Published

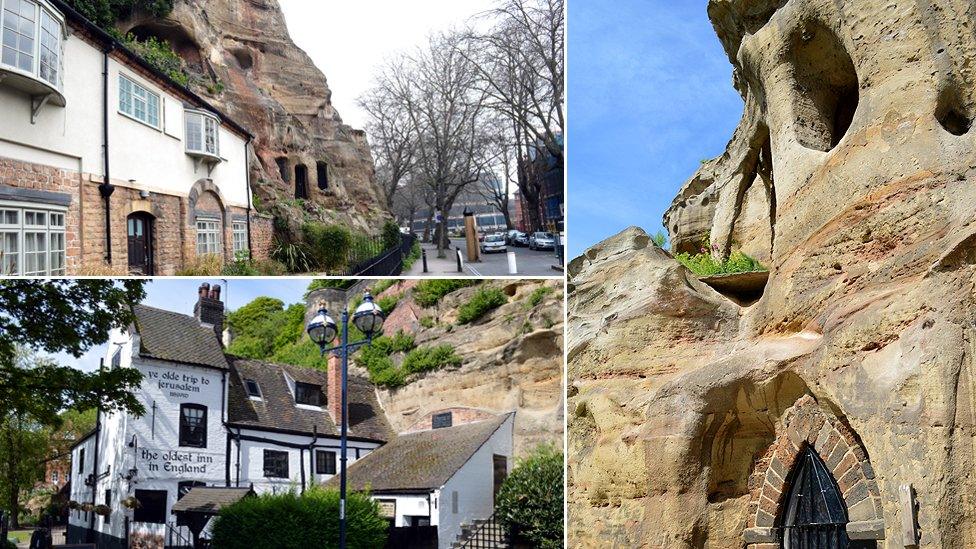

Nottingham's 544 caves have been used as everything from dungeons to bomb shelters throughout history but 100 of them were only discovered in the past four years. Take a look at how many of the caverns are still in use today.

In 1330, the young King Edward III and a group of conspirators crept through a secret tunnel into the city's castle and took prisoner Roger de Mortimer, a nobleman who had until then effectively been England's ruler.

The tunnel later became known as Mortimer's Hole but this daring coup was made possible by the city's network of man-made caves within the sandstone rock.

The caves appear to have existed for as long as Nottingham and as far back as 868, a Welsh monk named Asser referred to the settlement as Tig Guocobauc, which means "house" or "place of caves".

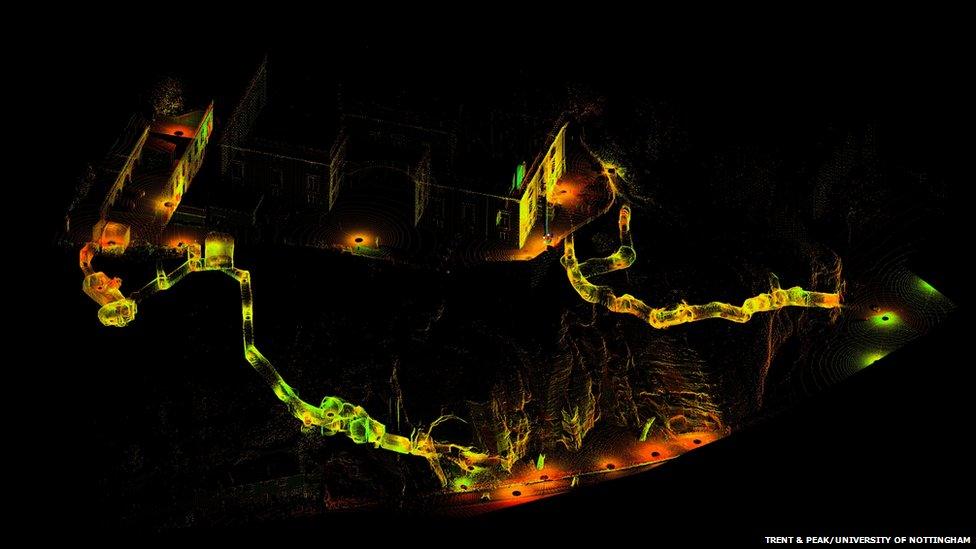

Archaeologist Dr David Strange-Walker, project manager of Nottingham Caves Survey, has been mapping the city's caves for the past four years and has recently discovered scores more than were previously known. The work has also led to the development of a new smart phone app to allow people to explore the city's caves from above the ground.

He said cave dwelling had been an intrinsic part of the city's history, particularly during the Industrial Revolution when an influx of people arrived to find work.

"The upshot was there was a great crush in the city," said the archaeologist. "[And] slum landlords were housing families in caves, which is all fairly horrific."

A laser scanned silhouette image of some of the caves - including Mortimer's Hole - beneath Nottingham Castle

Despite the 1845 Enclosure Act, which made it illegal for people to live in caves within Nottingham, many still had to find somewhere to live.

"Areas outside the city had caves [and they] became like shanty towns," he said. "Some caves had proper frontages, others had a sheet of metal over the front, no fresh air, sanitation, nothing."

Deep beneath the Broadmarsh Shopping Centre are the last remnants of Drury Hill, one of the streets in the former 19th Century slums of Narrow Marsh, where poor sanitation led to the spread of cholera, tuberculosis and smallpox.

Whole families would sleep and eat in one room, with some even living in grotto-like caves below in a desperate attempt to solve the problem of overcrowding.

Near to the ruins is the UK's only known underground tannery where eight-year-old children lived and worked in appalling conditions, filling vats with urine and excrement to create ammonia for the tanning process.

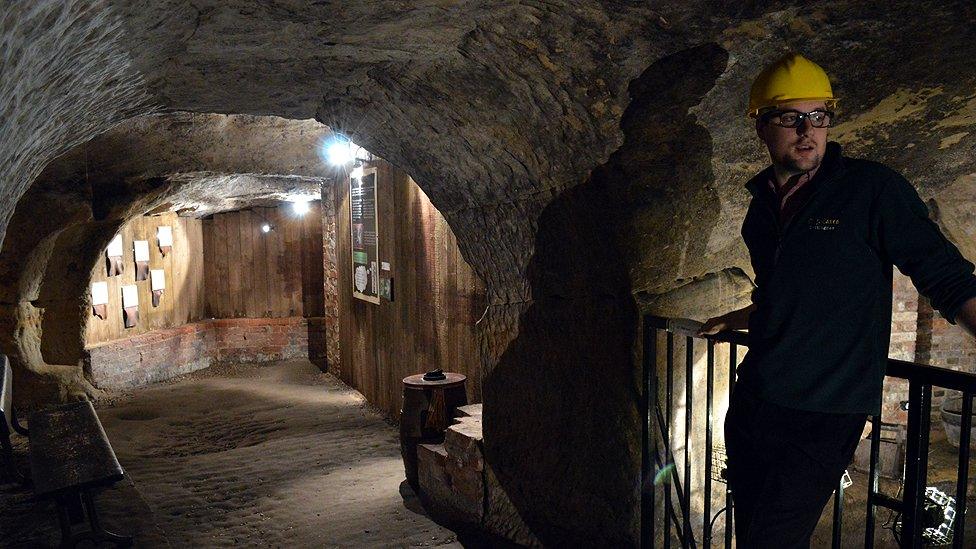

City of Caves has original basement walls from the Drury Hill slums and tanneries dating back 700 years

Today, the area is used as the City of Caves tourist attraction and is the only part of Nottingham's vast subterranean network that is open to the public to explore and learn the grisly truth about the city's cave dwelling heritage.

Andy Fowler, one of the attraction's tour guides, said conditions were particularly nasty for the child workers, who also had to live in the foul-smelling caverns, during the 1500s.

He said: "One of their jobs was to mix fresh animal skins with water and quicklime solution to strip them of their flesh and fat. They would have ended up with hands like claws as a result."

However, despite their poor life expectancy and the wretched conditions, the one thing they were immune from was the bubonic plague.

Mr Fowler said: "The rats and mites [that spread the disease] weren't found in the tannery so the workers weren't affected by the plague. Life was a double edged sword, really."

As part of the tour, visitors can pass through an old pub cellar which has a hole the size of a golf ball in its ceiling. It is thought the cave was used by criminals or other plotters who could be alerted to the presence of the authorities by someone dropping stones through the hole from the street above.

Legend has it that Dick Turpin, or even Robin Hood, were the plotters in different eras, but it was more likely to have been members of the Luddite movement in the 19th Century.

Paul Watkins and others at apartments in Castle Boulevard use the Lenton Hermitage caves as a bike shed

Lenton Hermitage, or Park Rock, a network of caves cut into an outcrop of sandstone in Castle Boulevard, was used as a dwelling during the 13th Century and later became a hunting lodge, a bowling club pavilion, a World War II air raid shelter and even a caravan showroom in 1985.

The large caves, which are protected as a scheduled monument by English Heritage, are hidden from view by several apartment blocks overlooking Nottingham Canal.

However, residents like Paul Watkins, are putting them to good use today as a secure area to keep bicycles but also to fight Gotham City's villains.

He said: "My kids use them as Batman caves and one of them makes little films in them, it's fantastic. But they're pretty annoyed with me that we're moving down the road."

Many caves around Nottingham were created for brewing, and storing, beer and ales due to their consistently cool temperature all year round.

The owners of the Hand and Heart, in Derby Road, use their ancient structure as a restaurant and said their customers love the novelty of dining in the caverns.

The Hand and Heart pub in Derby Road has a long cave and is used for dining

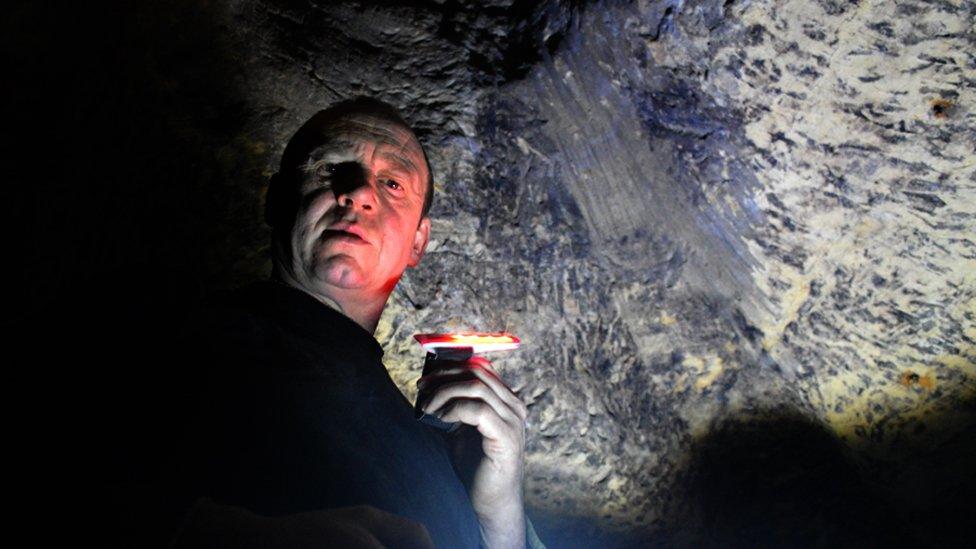

The road is a hotbed for caves and some are still being discovered. Property developer Paul O'Shea bought a 150-year-old building in Derby Road, in January, to convert into student apartments, when he found a trapdoor leading deep into long forgotten chambers.

Mr O'Shea, who is looking at turning his caverns into a bar, said: "It was a bonus [discovering it] and everyone has been amazed by what's down here."

He contacted Dr Strange-Walker who at first thought it was probably a cave he knew about but a shock was in store.

He said: "I had a good look at all our records and found no record of it whatsoever, so for us it's a brand new cave, number 544. A new cave is always very exciting."

Dr Strange-Walker believes it was used as a cellar for a long lost pub known as The Old Milton's Head which dated back to the 1840s.

He added: "It's a really good example that there are lots of other caves around the city that we don't know about and there aren't any records for.

"They do keep turning up and something we want to do is look for more of these caves so we can boost numbers up to 600, 700, who knows."

Paul O'Shea bought a house in Derby Road and discovered a cave beneath the property