Civil War centre opens in Newark

- Published

Newark's National Civil War Centre is the first of its kind in the UK

The Civil War was one of the bloodiest chapters in Britain's history and wiped out one in 20 of the population. Now, almost 370 years after the conflict, its story is being told in a dedicated museum.

The conflict from 1642 to 1646 split families as they took up sides with the supporters of King Charles I, known as Cavaliers, or the Parliamentarians, nicknamed Roundheads.

The £5.4m National Civil War Centre has opened in Newark in Nottinghamshire, a Royalist stronghold which came under siege three times until the King surrendered the town in 1646.

Broadcaster and historian Michael Wood said it was "amazing" there was nowhere in the UK dedicated to marking the conflict until now.

"It is the first such exhibition to tell the story of the Civil War from start to finish," he said.

"And it's a tale we all should know, drawing in the people of the British Isles from Elgin to Cornwall and from Newark to Haverfordwest and indeed over the sea to Dublin and Drogheda."

Paid for by the local council and a £3.5m Heritage Lottery grant, its exhibits give a fascinating insight into the gruesome realities of everyday life during the tumultuous period.

The buff coat bullet hole

John Hussey's buff coat is pierced by the musket ball that killed him

It is rare that items like this can be traced back to an individual

A Roundhead musket killed Royalist John Hussey, of Doddington Hall in Lincolnshire, while he was defending the town of Gainsborough in 1643.

His breastplate and buff coat - complete with bullet holes - bring to life the reality of the battlefield, according to Michael Constantine, manager of the centre.

"Some of the swords have got nicks out of them where they've been used in anger but you don't see breastplates that have got the actual musket ball holes in them," he said

"Nor are you usually able to put that musket hole to the leather coat that was worn behind it and to be able to put a name and a face to that character."

The angle of the shot indicates he was shot from a greater height, perhaps from horseback, he said.

Royal branding

Terrifying "oven mitts" were used to "brand" Royalist deserters

It might look like an oven mitt but this gruesome implement was used to inflict a bloody punishment on those caught deserting the King's army.

Dozens of pins would press into the unfortunate soldier's palm forever imprinting the mark of the Crown.

"They must have had a department to think up such creative and gruesome forms of torture," said Richard Darn, from the centre.

"We forget what a bloody battle it was - 5% of the population died," he said.

'A better ending'

The man who walked Charles I to his beheading wore this buff coat

Another coat with a fascinating story belonged to Colonel Francis Hacker from East Bridgford in Nottinghamshire.

He was the officer in charge of escorting Charles I to his beheading and was one of a number of signatures on the king's death warrant.

"After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660 King Charles II came after some of the people who killed his father. Hacker was amongst them," Mr Darn said.

"He was executed but he didn't have the torturous death of being hanged, drawn and quartered because he was very kind to the King and treated him with a lot of courtesy.

"He got off with a better ending."

Hacker's family, like many others, had split loyalties - one Royalist brother died during the siege of Newark and the other lost his hand.

But he chose the Parliamentary cause and clearly became a significant figure.

Battlefield bone saws

Bone saws and a musket ball remover hint at the gruesome nature of 17th Century warfare

"If you are going to amputate somebody's arms you are going to need it to be fast," said Mr Darn.

And bone saws were the best available tool for the job.

But what if you needed to remove a musket ball? A long pointed implement would be screwed into the wound to extract the shot.

An upcoming major exhibition at the National Civil War Centre will be based on research by the University of Leicester about battlefield medicine and the advances that were made during the Civil War.

Siege silver

Diamond-shaped siege coins were found in large hoards in Newark

They were used to pay soldiers and buy food during the sieges

Rare coins, which were found buried in hoards in Newark, were made in the town in preparation for a siege, according to Mr Darn.

They were cut from a silver plate into diamond shapes to avoid wastage and were used to pay troops and issued to locals to buy food.

The town was under siege for six months from November 1645, during which time it was completely cut off from the outside world.

Mr Darn said it was difficult to establish why the coins were in the ground, but museum experts continue to speculate.

"Did the owner plan to dig them up later but was killed in the war," he added. "Or did he simply forget where he'd buried them?"

Soldiers' plague fears

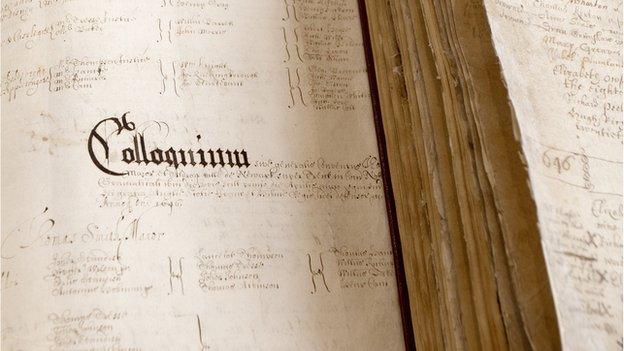

Archive documents reveal the details of everyday life in war torn England

Part of the reason Newark was picked as the home of the Civil War centre was because the town's history is remarkably intact.

Civil War expert Stuart Jennings, from Warwick University, who examined archived documents recently discovered in the town said they were a unique insight into the minutiae of everyday life.

"This kind of material does not normally survive the Civil War, so we are getting a rare glimpse into ordinary lives," he said. "We have records of poor relief detailing how money was raised and to whom it was paid during the third siege.

"There is a petition from a man with seven children whose house was blown up by cannon fire and receipts for food and medicine for plague victims."

When the town was surrendered, plague was endemic and Parliamentarian and Scottish soldiers steered clear of the town rather than plunder or burn it to the ground.

Information from the archive has been used by the National Civil War Centre, which also includes a smart phone app trail, external around town, to propel visitors back in time.

Manager Michael Constantine said: "We tell the story through the eyes of those who took part, whether that's Charles I or the servant girl lamenting meagre rations."

The Newark sieges

The most accurate reconstruction of the town as it would have looked in 1646 has been produced

Nearly 900 re-enactors will recreate the sieges to mark the opening of the centre on Sunday and Monday. But what actually happened?

Located at a crossing of the River Trent at the crossroads of the Great North Road and Fosse Way, Newark held huge strategic importance.

The last of three sieges saw 16,000 troops seal off Newark from November 1645 to May 1646.

An outbreak of plague added to the town's woes as a third of the town's 6,000 inhabitants died but the Cavaliers refused to surrender.

King Charles hoped to drive a wedge between them and their Parliamentarian allies and surrendered the town to them, but they insisted that Newark must yield immediately.

Half-starved and disease ridden, 1,800 Cavaliers marched out. It was the beginning of the end for Charles who was executed by Parliament three years later.

The most accurate reconstruction of how the town looked in 1646 has been commissioned by the National Civil War Centre.

Visualisation expert Simon Fleming examined siege plans produced by both sides of the war, accounts of the siege and 17th Century military manuals to create it.

King Charles I surrendered Newark to the Parliamentarians in 1646

- Published14 March 2015

- Published16 January 2015

- Published5 January 2015

- Published20 October 2014

- Published13 May 2014

- Published31 May 2012

- Published10 September 2010