Nottinghamshire coal mining ends with Thoresby closure

- Published

Thoresby Colliery was once said to be one of the most successful in the country

Thoresby Colliery closes on Friday, marking the end of a 750-year history of mining in Nottinghamshire.

As the last coal is brought to the surface at Thoresby it leaves just one deep coal mine in England, Kellingley Colliery in North Yorkshire - which is itself expected to close by the end of the year.

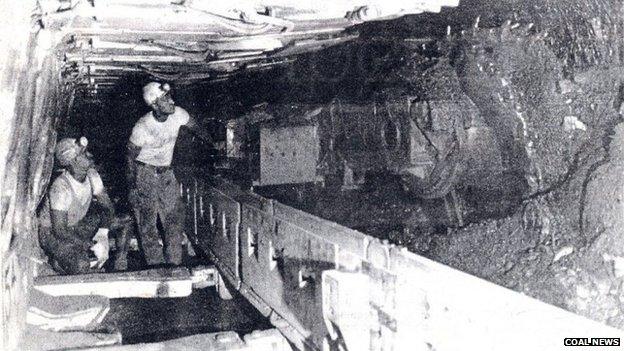

At one time Nottinghamshire, with 42 collieries and 40,000 miners, was one of the most successful coalfields in Europe. But as the industry comes to an end in the county, what memories do former miners have of their time in the pits - and what effects have closures had on former mining communities?

Thoresby Colliery miners will work their last day shift on Friday

Former mining surveyor turned author, Robert Bradley, said Thoresby at one time produced more coal than any other colliery in England with profits of £50m a year.

"It produced 100,000 tonnes in a week - some of the smaller mines did that in a year," he said.

"There was a good atmosphere working in the mine and everyone thought they had a global job for life."

Many of Nottinghamshire's towns and villages were built around the collieries and for the mining families.

Mr Bradley, 79, said the closures of mines at Ollerton in 1994 and Bilsthorpe in 1997 "devastated" these communities.

"Most people lived where they worked," he said.

"It was expected back then the sons of miners would all go into mining and the girls would be sent to factories and shops.

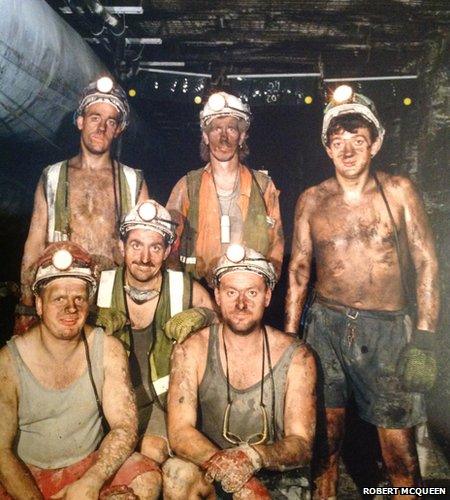

Robert McQueen (top right) moved from colliery to colliery as they closed down

"But once they closed, there were no jobs so they had to travel out of the village to find work."

He said British Coal once paid miners "an obscene" amount, which eventually cost the company a lot of money.

Robert McQueen was one of thousands of Scottish men who moved to Nottinghamshire to work in the pits.

"Places were shutting down left right and centre in Scotland so it was great coming down," said the 55-year-old.

"There were lots of Geordies, Scots and eastern Europeans who came over just after the war.

"Nottinghamshire at one point had the top five collieries in the country.

"Production was going through the roof and we were making lots of money.

"When you met lads from other places people couldn't believe how much we were on. We were getting £40-50 bonuses and they were getting 50p to £1.70."

But the situation soon changed as money ran out and jobs were threatened with pit closures.

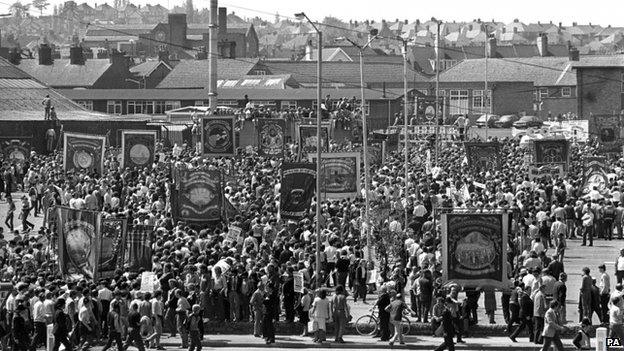

Miners' strike 1984

March 1984 saw the biggest industrial action in British coal history with miners going on strike over pay disputes and pit closures.

The choice of whether to join a picket line or continue working divided workforces, caused arguments within families and began fights across the country.

Arguments over the tactics of the NUM (National Union of Mineworkers) also saw the formation of a second union for workers - the UDM (Union of Democratic Mineworkers).

In some cases men who chose to continue working were given police escorts to the pits.

As the situation became worse, many miners refusing to work found themselves struggling financially and kitchens were set up by families to provide food for those who could not afford it.

The strike ended a year later after the National Coal Board offered pay incentives to workers and NUM members voted to return to work.

Mr McQueen worked in the county's pits for 35 years and was made redundant from Thoresby last year.

"You just knew one day your number was going to be up and there was not going to be anywhere to transfer to.

"There is a tinge of sadness and I miss the camaraderie."

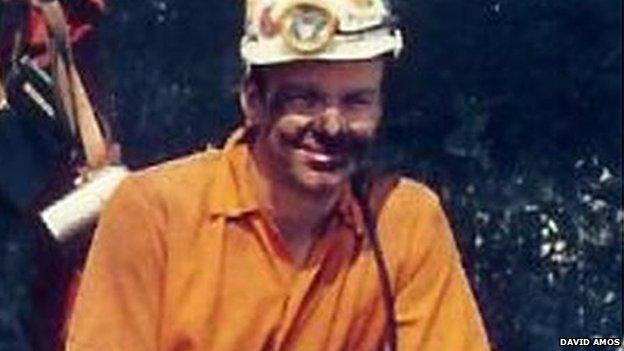

Local historian Dr David Amos said the industry had been in decline for the past 50 years.

"Mining played a significant part in the industrial revolution," he said.

"It built the towns, economy and communities in Nottinghamshire from the 19th Century to the 1990s but the miners' strike probably accelerated the demise of the industry.

David Amos worked at Annesley Colliery and is working to carry on the heritage of mining in Nottinghamshire

"It is the end of a significant chapter in the industrial revolution in this county and soon the end of coal in Britain as a whole."

Like many, Dr Amos was the last of generations of miners in his family to work in the pits.

Tony Kirby, who joined the industry in 1985 following the major strikes, will be one of the last workers to leave Thoresby and said it would be particularly poignant for him.

"Mining has been in the family since the 1860s so I wanted to follow my granddad, uncles and brother to carry on the tradition," the 51-year-old said.

"When we were growing up there used to be four or five thousand miners living in Eastwood and we used to have parties for families and trips to the seaside.

"I had hoped my sons would follow me down the pits but it's sad they'll never work in mining."

Residents fought to save the headstocks at Clipstone Colliery when it closed in 2003

Several projects have been started aiming to preserve the heritage in Nottinghamshire mining towns and to educate people on the impact of coal mining on the county.

The original headstocks at Clipstone Colliery, which were the tallest in Europe when built, are being regenerated and turned into an attraction in the hope of keeping the history alive.

And statues and mini museums are being planned at other former colliery sites.

And if the country's last remaining deep coal mine - at Kellingley - does indeed end production in December, it will mark an end to British coal mining as a whole.

- Published17 May 2013

- Published9 March 2015