Cooling towers: Eyesores or sights for sore eyes?

- Published

Could the sun be setting on cooling towers?

All coal-fired power stations will be closed by 2025, the government has announced, signalling the beginning of the end for their cooling towers. But are the smooth curves that dominate the landscape eyesores that should be torn down or an important part of our heritage?

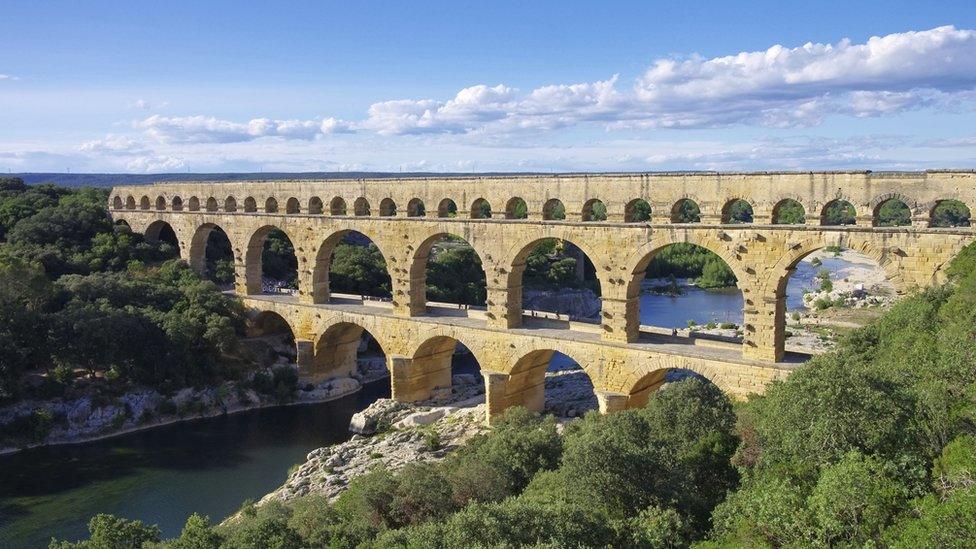

If a building is industrial does that automatically disqualify it from being beautiful? In the classic children's comic Asterix and the Golden Sickle, the moustachioed hero decries the creation of the Pont du Gard, exclaiming "the Romans are ruining the landscape with all these modern buildings!".

Today, it is one of the finest examples of Roman architecture and majestically frames the River Gardon in the south of France.

The Pont du Gard is now a Unesco world heritage site

Could coal-fired power station cooling towers, those curved chimneys that dominate landscapes across the UK, one day be considered 20th Century versions of the aqueduct?

"You might think of them as an ugly intrusion into the landscape but actually I quite like them. They have a simple elegant shape, really, I would be sad to see them go."

It is difficult to imagine Attenborough Nature Reserve without the cooling towers as a backdrop

This is the verdict of Nottingham Civic Society's Hilary Sylvester on the Ratcliffe-on-Soar power plant. And she does not think she is alone.

"They provide a point in the landscape," she said. "People probably did not want them when they were first built but they've been there for so long they are a feature.

"Putting a building in the landscape doesn't necessarily ruin it, and an industrial building doesn't have to be awful."

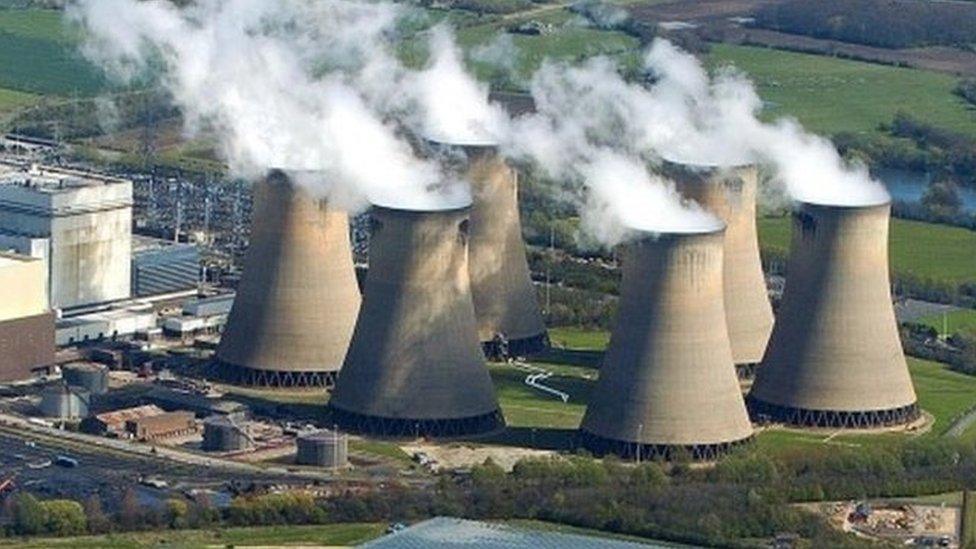

Thanks to its links with mining, Nottinghamshire has three of the largest coal-fired power stations in the UK - Cottam and West Burton, near Retford, both in the north of the county, and Ratcliffe-on-Soar close to the border with Derbyshire and Leicestershire. And it used to have more.

But like Nottinghamshire's coal-mining industry, they face being consigned to history's slag heap following Energy Secretary Amber Rudd's announcement last week.

Power generation in the UK

There are just 13 coal-fired power stations left in the UK, one each in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland and the rest in England

Combined, they are capable of generating 20,618 MW or a quarter of the UK's total energy capacity

Of these, nine have cooling towers but several are already undergoing conversion to another power source or consulting on closures

The cooling towers - or to give them their full name "natural draft wet cooling hyperboloid towers" - emit water vapour, not smoke

A small number of older nuclear power stations have similar cooling towers, including Chapelcross, near Annan in Dumfries and Galloway, although it was demolished in 2007 (above)

Ratcliffe power station has often been the focus of protests

Ms Rudd revealed coal-fired power stations without carbon capture technology are to be closed down by 2025.

Europe's largest coal-fired power station Drax, in North Yorkshire, recently announced it is cancelling investment, external in the only scheme linked to a coal power station.

It is now clear the government favours gas over coal, but coal-fired power stations cannot be converted for this use.

Industry representative body Energy UK said it would be best to "knock them down and start afresh" - although with a ready-made connection to the National Grid it should prove easier to rebuild Britain's power stations where they stand rather than choose a new location.

Drax, near Selby in North Yorkshire, is the largest coal-fired power station in Europe and generates some 7% of the UK's electricity

All of which points to an extremely uncertain future for cooling towers, those vast symbols of industry to which many people have perhaps surprisingly become rather attached.

Their towering forms, visible for miles around, are the signal to many commuters they have nearly reached the comforts of home.

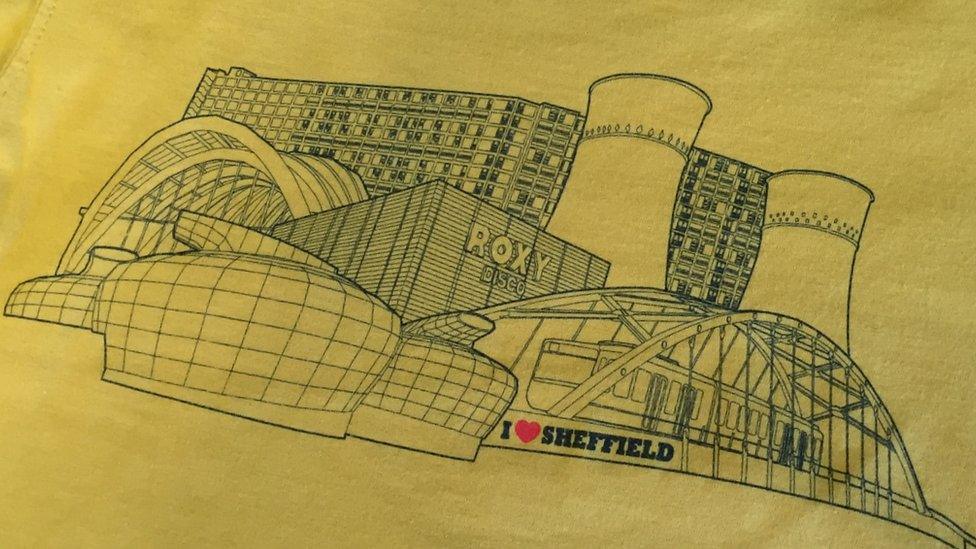

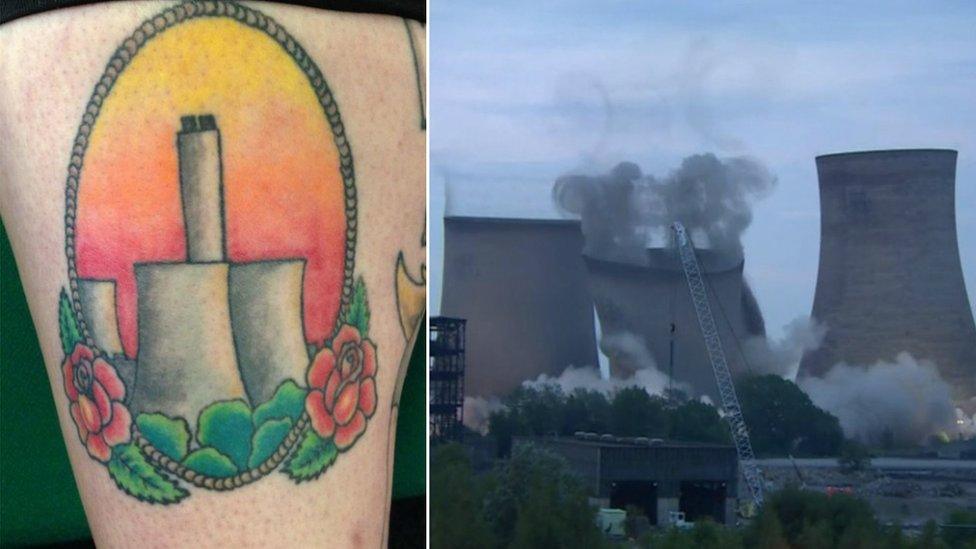

In Sheffield, the since-demolished Tinsley cooling towers were such an integral part of the city's backdrop they were emblazoned on promotional T-shirts, and so fond was one woman of Didcot power station in Oxfordshire she had it tattooed on her leg.

Clare Price from the Twentieth Century Society - which campaigns to preserve post-1914 British architecture - went as far as to say cooling towers were like modern versions of the church tower - that familiar landmark that means you are home.

But they are also an important part of British history.

"We think it's a real pity that we could lose the cooling towers. They have a fantastic sculptural form and are a striking feature of our landscape," Ms Price said.

"They are a very important part of our industrial history and are a part of our culture."

So could, or should, we prevent every cooling tower from being razed to the ground?

When West Burton power station became operational in 1969 it dwarfed a nearby windmill used to grind animal feed

The giant structures contrast with the night sky makes a striking photograph, such as these near Retford in Nottinghamshire

Neville Stankley is an expert in heritage from Nottingham Trent University.

"We have lost almost all evidence of the mining industry in Nottinghamshire. The danger is the power stations will all be wiped away, almost as if they never existed.

"It will be interesting to see if anything is saved. At the moment you don't get the feeling there's an appetite for preservation, but then you take it for granted until all of a sudden it's under threat."

But what can be done with a redundant cooling tower?

At Wunderland Kalkar a merry-go-round has been installed in a cooling tower

The Twentieth Century Society suggested looking to Germany where alternative uses have been found, such as Wunderland Kalkar, a theme park inside a disused nuclear power plant.

This, though, would require a sizeable investment, but there is hope.

Next month, Historic England is holding a conference with the Heritage Lottery Fund and the Prince's Regeneration Trust to explore ways of reusing industrial buildings, external.

And Historic England says it is working with the power companies and National Grid to "agree an appropriate conservation strategy".

Mr Stankley would like to see some of the towers preserved - particularly in Nottinghamshire's Trent valley - but is not optimistic.

"It will be really interesting to see what happens. Maybe in 20 years' time people will be saying 'let's go down to Ratcliffe for a great day out'. That would be fantastic - but I won't hold my breath."

- Published18 November 2015

- Published20 November 2015

- Published15 July 2012