How familial DNA trapped a murderer for the first time

- Published

Gladys Godfrey was raped and murdered in her bungalow in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire

The pioneering technique used to identify a British widow's sadistic killer has led to hundreds of crimes being solved around the world. How was familial DNA searching used to catch a murderer for the first time, 15 years ago, and more recently the suspected Golden State Killer?

WARNING: This account includes some graphic descriptions of violent crimes

Gladys Godfrey's murder left people from her community in fear, and it shocked even seasoned detectives working on the case.

The 87-year-old widow was sleeping in her living room in September 2002 when 21-year-old Jason Ward entered the bungalow and began raping and beating her.

"She used to sleep in the chair, she would never go to bed," remembered her niece Sandra Linacre.

"She used to say 'you die in bed'."

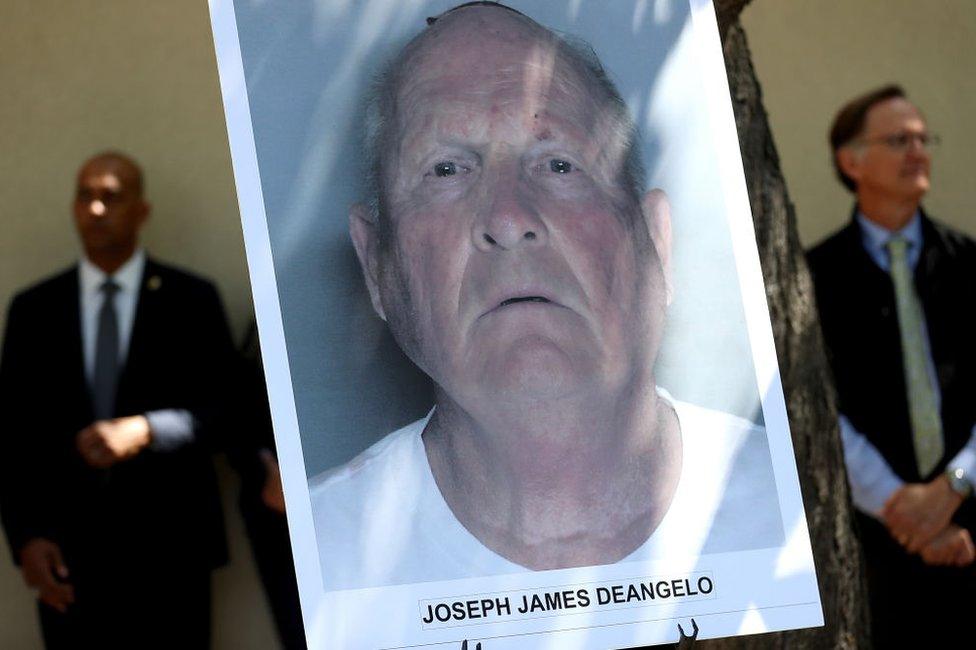

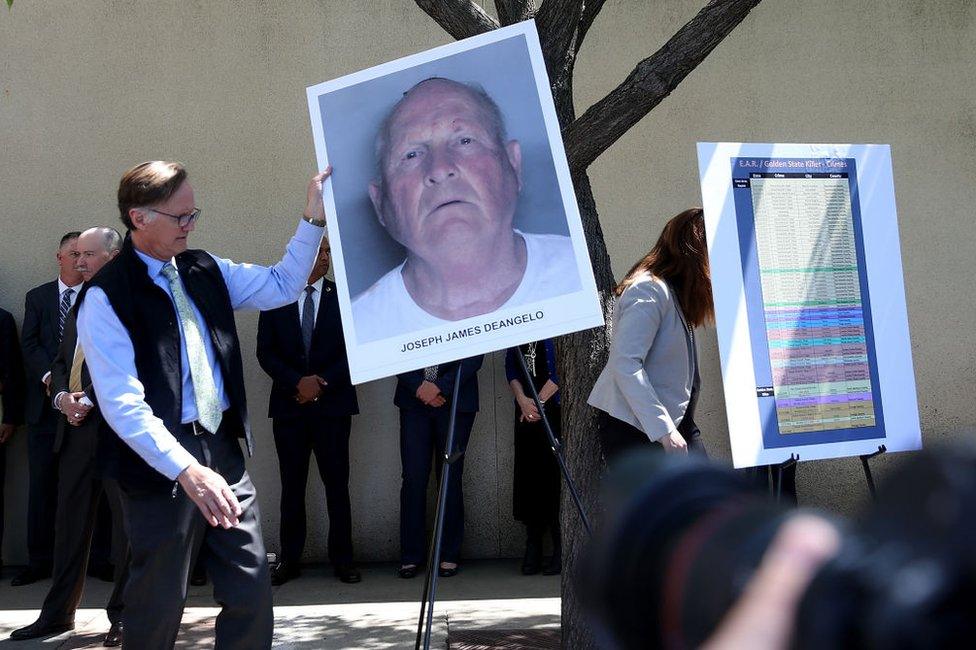

Joseph James DeAngelo has been identified as the suspected Golden State Killer due to familial DNA searching

Mrs Godfrey also had a habit of leaving her bungalow in Mansfield unlocked. She may well have recognised her attacker, because the same young man had entered her home in April 2001 and knocked her to the floor, before exposing himself.

Despite being 4ft 11ins tall and weighing just six stone (38kg) she managed to defend herself during the first attack. She hit Ward with a lemonade bottle and he fled taking her handbag.

Sadly, Mrs Godfrey was not so fortunate when Ward returned 16 months later.

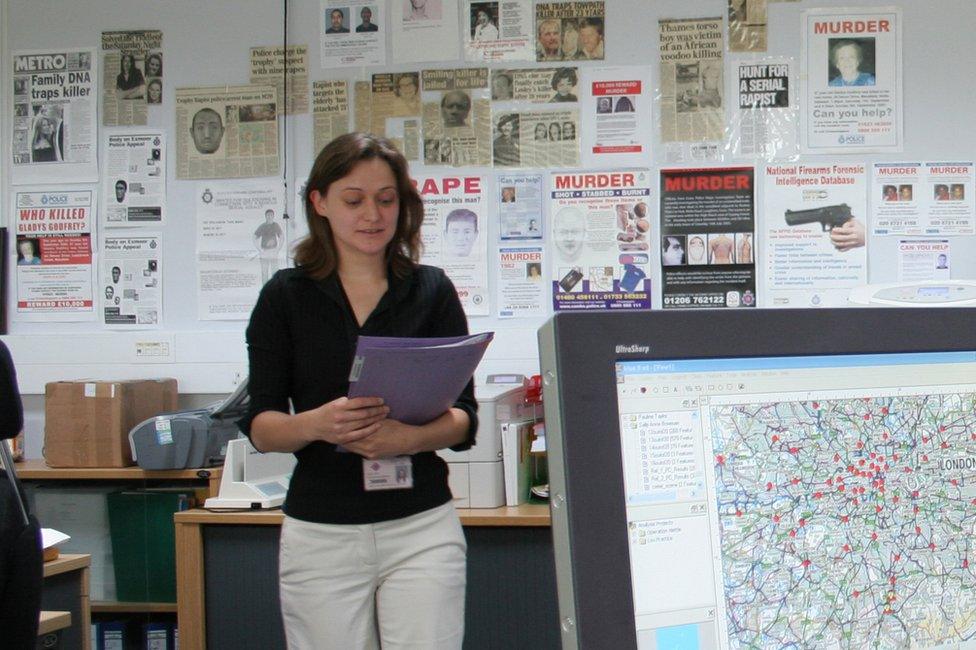

Frances Bates, pictured here in 2005, pioneered familial DNA searching to find Gladys Godfrey's killer

He beat her. He stamped on her. He kicked her. He strangled her. He pulled out clumps of her hair.

Mrs Godfrey's cause of death was head injuries and manual strangulation. Her injuries included a fractured skull and broken neck. Her face and body were in such a distressing state that her niece was not allowed to identify her.

Listen to solicitor Paul Bacon looking back at the murder of Gladys Godfrey

"It was one of, if not the most horrendous case, that we have ever investigated," recalls Kevin Flint, who was the senior investigating officer for Nottinghamshire Police.

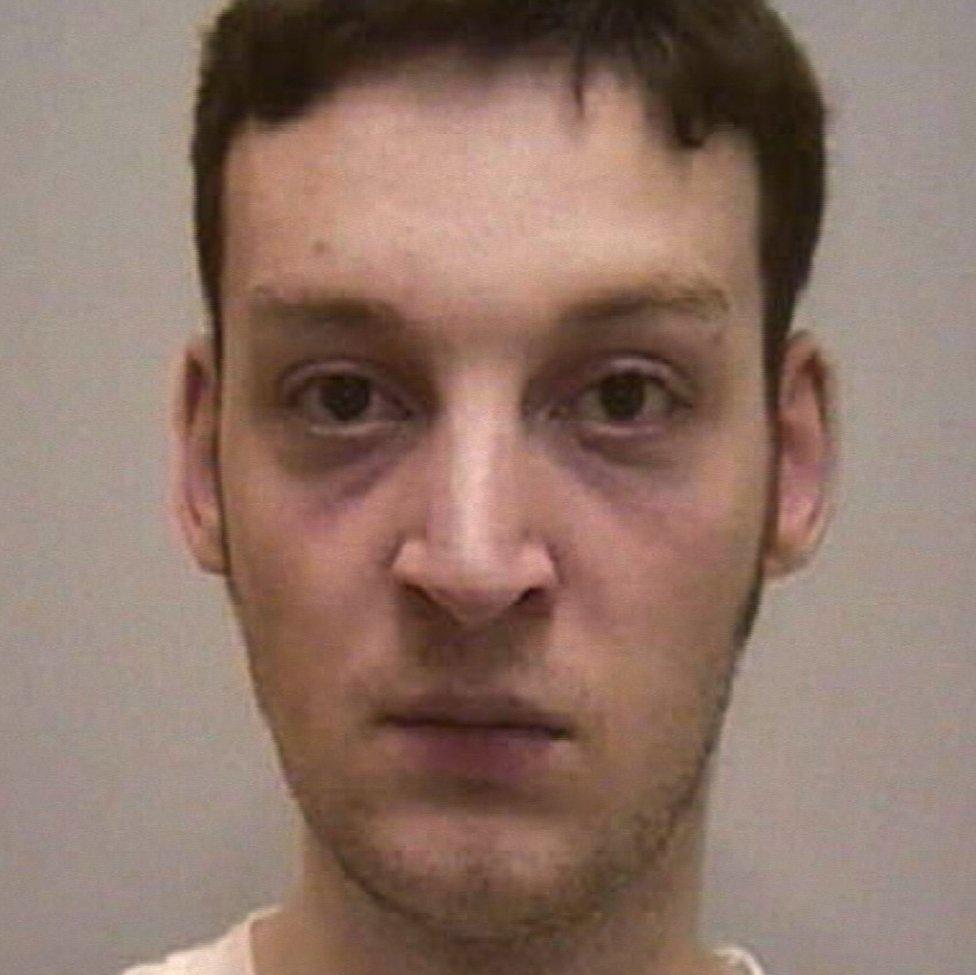

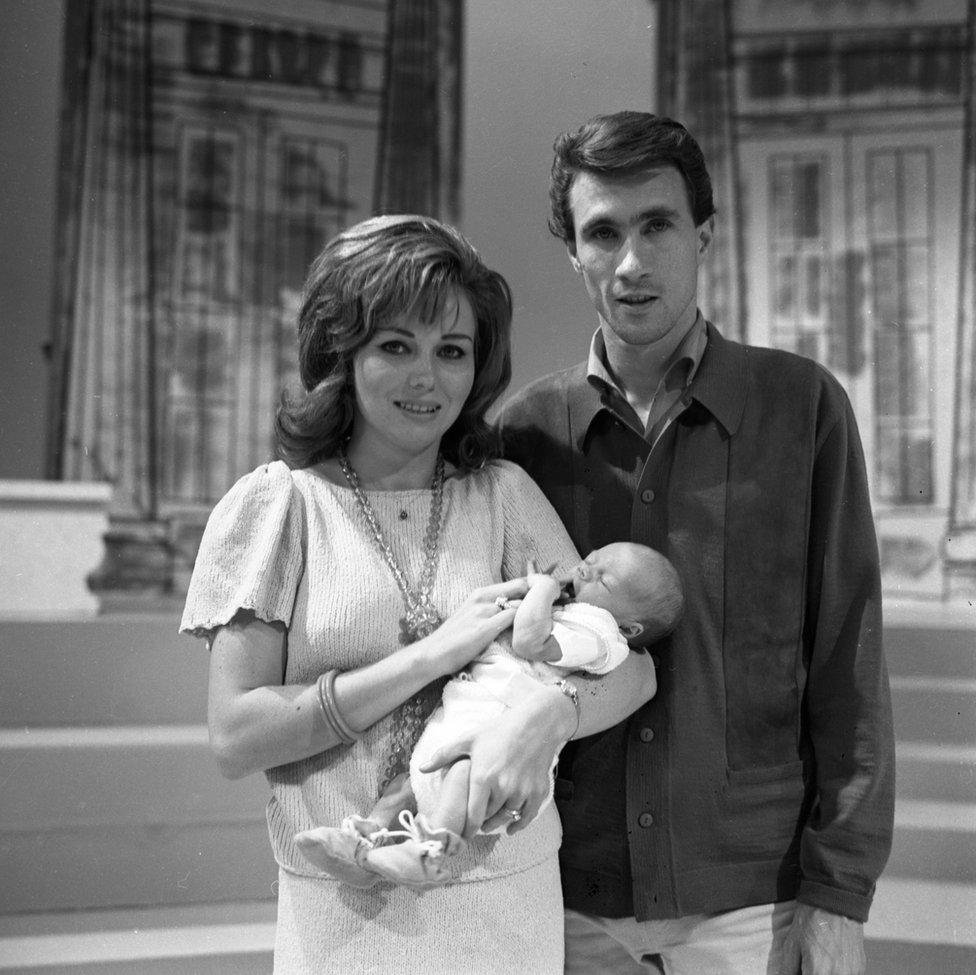

Jason Ward was 21 when he brutally raped and murdered Gladys Godfrey

Police were determined to catch the man responsible, but a year passed and he was still at large - and Gladys's family were giving up hope that her killer would ever be brought to justice.

Detectives had a sample of the killer's DNA from the murder scene and this matched DNA samples from the previous attack. They therefore knew that the same man was responsible for both crimes.

Jason Ward had attacked Gladys Godfrey 16 months before he returned to her bungalow

However, efforts to trace the killer through his DNA profile had been fruitless as Ward had never been arrested and was therefore not on the National DNA Database.

Police then began the arduous task of taking swabs from 1,100 men in Mansfield and beyond. Again, there were no matches.

Mansfield's MP Alan Meale described the lack of progress as disappointing

Phil Cumberpatch, a detective constable who worked on the case, was among the officers who went knocking on doors within a targeted area around Mrs Godfrey's home.

"Knowing what happened to Gladys was your motivation," he said.

"Every time you thought you were having a bad day you thought of what happened to Gladys and cracked on."

The Forensic Intelligence Bureau had grown by the time this group photo was taken in 2005

Meanwhile, scientists in Birmingham were working on something that would prove pivotal in the case being cracked: familial DNA searching.

It involved DNA samples from a crime scene being passed to the National DNA Database in order to find very close matches, rather than exact matches. The theory was that some of these close matches might be related to the suspect, because they had such similar DNA. Police could then narrow down their search.

You might also be interested in:

This work was being pioneered by the Forensic Intelligence Bureau, which had been formed that same year - 2003.

It was part of the Forensic Science Service, which used to provide support to police forces across England and Wales before the government controversially closed it in 2012.

Gladys Godfrey's niece, Sandra Linacre, feared the killer would never be caught

"The Forensic Science Service decided they would formalise the use of forensic intelligence and set up the bureau of six people," said Richard Pinchin, who was head of the newly-formed Forensic Intelligence Bureau (FIB).

"We established the first forensic intelligence bureau in the world, which primarily was concerned with looking at DNA from scenes of crime and analysing that and trying to forward investigations where no other information was available."

Familial searching was first put to use when a brick was thrown through the windscreen of a lorry on the M3 in March 2003, causing the driver to have a fatal heart attack.

Craig Harman was traced through DNA he left on the brick he threw and was later jailed for six years for manslaughter, external.

Gladys Godfrey's murder terrified other people living in the area

But the Gladys Godfrey investigation would become the first time familial searching had ever been used to trace and convict a murderer.

Frances Bates was the senior intelligence officer who led on that work.

"I would love to say there was a eureka moment but with familial searching it wasn't really like that," she said.

"The result is actually quite a long list of potential relatives of an offender and it's down to the local police to use knowledge that they have access to."

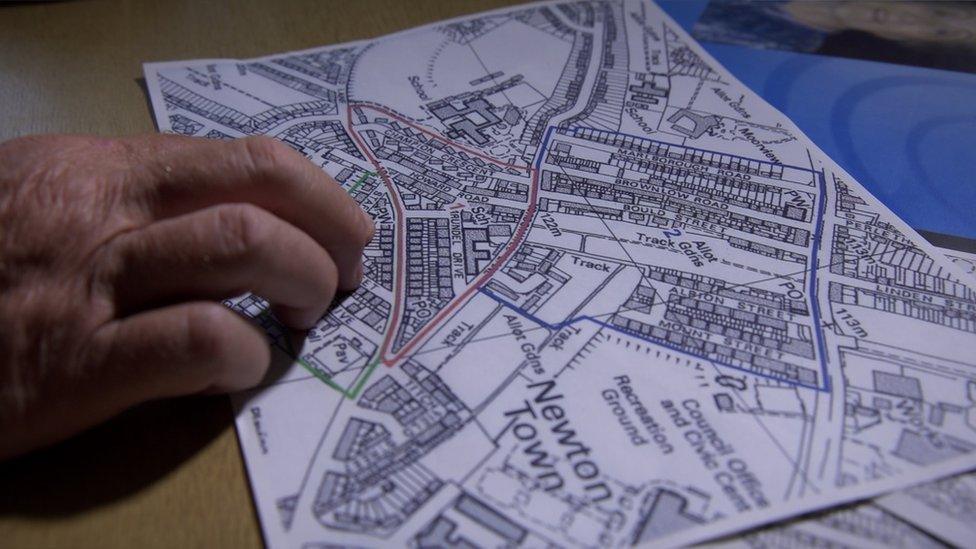

Frances Bates (left) used parameters such as geography to refine the list

This meant Miss Bates and her colleagues needed to work closely with the police investigative team. They visited Nottinghamshire, where they had a tour of the local area and saw videos of the crime scene.

She produced a list of people who had very similar DNA to the sample taken from the Gladys's home.

"It wasn't a quick fix; it wasn't just providing the police with one name," said Miss Bates.

"It was in fact quite a long list of people who could be related to the offender."

They used parameters such as geography to refine the list and create a top 20 for police to look at. It just so happened that the second person on the list was a male relative of Ward.

"They were able to go to the close relative of Jason Ward, ask him the right questions and then find Jason in order to take some samples," said Mr Pinchin.

"Strange" and "weird" Jason Ward was eventually identified as the killer

When Ward's DNA was tested it matched with the sample from the crime scene, as did his fingerprints with those left at Gladys's bungalow.

Phil Cumberpatch recalls the moment he heard Ward had been identified as the killer, in December 2003.

"I can remember wondering who had taken the swab, because it's friendly competition," he said.

"You wanted to be that person, but when you realised you weren't you were still happy.

"You were still chuffed to bits that maybe Gladys would get some justice."

Jason Ward lived outside of the targeted area where police had taken swabs from men

Gladys's niece said she was "absolutely shocked" when she found out the killer had been caught.

"What was nice about it was it was just two or three days before my birthday, so it was like a birthday treat that they had actually found him," said Mrs Linacre.

"I was so shocked to see how old he was. For a young lad like that, I just couldn't believe it."

Ward worked as a machine operator at a plastics moulding company

Jason Ward lived in Bentinck Street, about a mile and a half away from Gladys's bungalow in Devon Drive.

He was a loner who lived with his parents, spent much of his time playing computer games, and had problems with alcohol and solvent abuse. A former classmate told the BBC at the time he was "strange, weird and easily led".

Ward initially denied killing Gladys but police had so much evidence he eventually pleaded guilty to rape and murder.

Frances Bates was at Nottingham Crown Court in May 2004 when a judge gave Jason Ward a life sentence with a minimum term of 22 years.

"I was sat in the public gallery, near the family, and to see the family's reaction and to see that they had got closure in this case meant a great deal to me," she said.

"I was only a small part in the case but to know that I had helped provide that closure was really important to me and something I still think about to this day."

Frances Bates, pictured here in 2018, said she still thinks about Gladys Godfrey's murder to this day

Richard Pinchin said the successful conviction was hugely important to the spread of familial DNA searching.

"I think it was pivotal," he said.

"Without that case, and without those people working together, we would not have been able to prove how effective this was."

Investment was ploughed into the Forensic Intelligence Bureau to help more investigations.

"It became famous throughout the world and we were invited to speak at international conferences, and that technology has spread throughout many countries that have advanced forensic science capabilities, such as America, to investigate crimes in their jurisdiction," Mr Pinchin said.

Paul Hutchinson was caught 25 years after he raped and murdered Colette Aram

In the UK alone, familial DNA searching has been used in 212 criminal cases since 2009 - the year to which government records date back.

It has notably been used to solve cold cases, such as the 1983 rape and murder of 16-year-old Colette Aram.

Her killer Paul Hutchinson had avoided capture for 25 years, until his son was arrested for a motoring offence in 2008. A routine swab was taken from the younger man and his DNA was nearly identical to that of the killer.

In the US, it helped crack the high-profile murder of Karen Klaas, the ex-wife of Righteous Brothers singer Bill Medley.

She had been sexually assaulted and strangled with her own tights in 1976, but her killer Kenneth Troyer was not identified until 40 years later. He had been shot dead by police in 1982, but establishing he was her murderer meant the family could finally get closure.

Karen Klaas, the ex-wife of Righteous Brothers singer Bill Medley, was strangled with her own tights

Earlier this year, familial DNA was used to identify the suspected Golden State Killer, a man thought to have committed multiple rapes, murders and burglaries across California in the 1970s and 1980s.

Investigators had DNA samples linking the crimes, but they were not a match for anyone on the FBI's national database.

The DNA evidence was uploaded to a genealogy website called GEDmatch, which identified several relatives of the killer. The list was narrowed down using information such as the killer's location and age.

The search eventually led to a former police officer called Joseph James DeAngelo, who was arrested and is currently awaiting trial.

The arrest of Joseph James DeAngelo was announced at a news conference in April

The case sparked privacy fears in the US, largely because investigators used a consumer service whose users unwittingly became "genetic informants". If even your distant relatives use these services then their DNA could get you jailed - provided you have committed a crime.

Curtis Rogers, co-founder of GEDmatch, told New Scientist that he spent two weeks not sleeping, external as he tried to figure out the ethics of the situation.

"Do we ensure that the privacy of all our users is protected? Or do we go after murderers who make Jack the Ripper sound like a choirboy?" he asked.

Joseph James DeAngelo is awaiting trial

Back in the UK, the service that pioneered the technique no longer exists, but the impact of the Gladys Godfrey investigation is still being felt.

"The seeds that were sown by that case are still active in most countries in the world," said Richard Pinchin.

"I'm very proud to know that I've helped that family, but also of the legacy of familial searching," said Frances Bates.

"To know that we started it and it has now spread across the world, and it's still helping solve cases today and provide closure to other families - that is very important to me."

You can see this story in full on BBC Inside Out East Midlands at 19:30 GMT on Monday on BBC One, or via iPlayer for 30 days afterwards.