Why are university students catching mumps?

- Published

Uptake of the measles, mumps, and rubella virus (MMR) vaccine has gone down in recent years

Mumps - a contagious viral infection that causes swelling of the glands - has been in the news this week following a confirmed outbreak at two universities.

A total of 223 suspected cases were reported, with 40 confirmed, across Nottingham Trent University and the University of Nottingham.

That has now risen to 241 suspected cases with 51 confirmed by Public Health England (PHE).

BBC News has taken a look at why this is and whether university students are still at risk.

Where else is this happening?

The numbers seem particularly high in Nottingham.

PHE said latest figures showed cases of mumps in England had decreased in 2018, with 1,024 confirmed cases compared with 1,796 in 2017.

There have also been a handful of reported cases at the universities of Bath, Hull and Liverpool and in the US - specifically Temple University, in Philadelphia, which has recorded about 100 people with signs of the infection.

There does not appear to be any reason as to why the Nottingham numbers are much higher, though experts have said it could be that there are more in the city who are not immune.

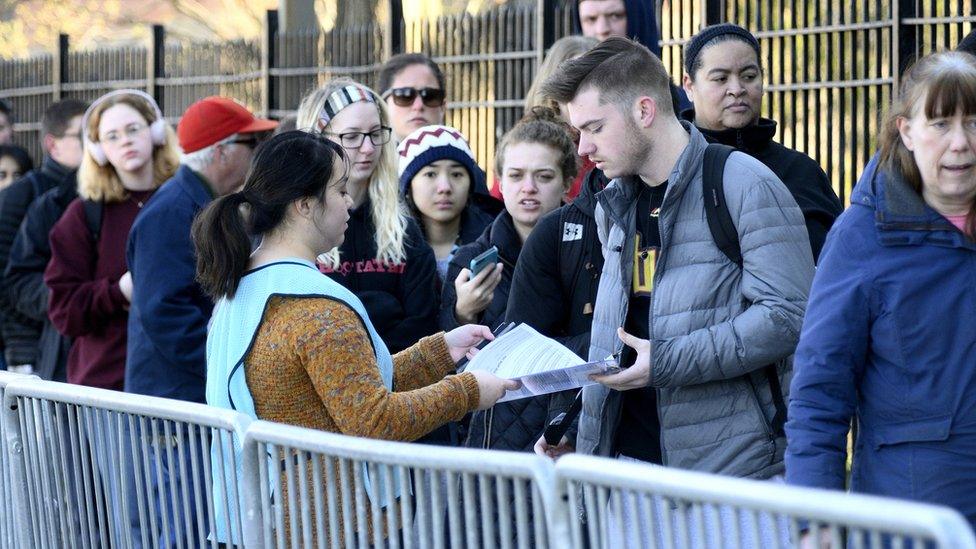

Students outside an emergency clinic at Temple University, in Philadelphia

Prof Jonathan Ball, from the University of Nottingham - an expert in viruses and viral vaccines and treatments - said it was affecting students because they gathered in "close proximity for fairly large periods of time".

This would include in halls of residence, lecture theatres or even at nightclubs, which hold specific nights aimed at students.

"The virus [could] spread fairly easy, especially if there are relatively large numbers of people who have not been vaccinated," he said.

A marine biology student at the University of Hull, who did not want to give his name, said he started feeling ill while on a field trip to the Isle of Cumbrae in Scotland.

He said a local doctor diagnosed mumps but also sent away a swab for it to be confirmed, as mumps is a notifiable disease in England and Wales, external.

The 19-year-old, who said he knew at least two others who had the symptoms, had to be isolated and driven home, avoiding public transport because of the risk of others being infected.

Can you catch it if you have been vaccinated?

Yes. Dr Vanessa MacGregor, from PHE, said it had seen a rise in figures recently, with teenagers and young adults who have not had two doses of the MMR vaccine "particularly vulnerable".

The NHS says, external the vaccine is part of the routine childhood immunisation schedule, in which a child is given one dose when they are 12 to 13 months old, and a second at three years and four months.

Dr MacGregor urged those who have not had the MMR vaccine - or only received one dose - to ensure they took up the offer of MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) vaccination.

Students in Philadelphia have been taking the MMR jab

The University of Hull student also said it was "strange" he had contracted the infection because he had received both doses and this had been confirmed by his father.

According to Prof Ball, the mumps part of the vaccine is the "least effective".

He said: "For the mumps vaccine, we expect about 88% of people vaccinated to be protected, whereas for the measles vaccine this is as high as 98%.

"If you then add unvaccinated people into the mix, it is easy to see how a relatively contagious virus as mumps can spread so easily."

Mumps was once common in children before vaccinations began in the 1980s

He said this was further complicated, because some people who are infected show little or no symptoms at all.

However, if the majority were vaccinated, those susceptible to the infection would benefit from "herd immunity", the level considered by experts to protect a population from a disease.

But, as Prof Ball states: "If you start to reduce the numbers of people being vaccinated, then that herd protection just isn't there."

Why is uptake of the MMR vaccine declining?

According to BBC Health Editor Hugh Pym, the reason for uptake declining in many countries was not clear.

The "damaging" work of discredited scientist and struck-off medic Andrew Wakefield in the 1990s "helped fuel the fire of the anti-vaccine movement," according to Prof Ball.

In 1998, the doctor led a study that linked the MMR vaccine to autism, impacting on the coverage of the vaccine, with rates dropping to about 80% in the late 1990s and a low of 79% in 2003.

The GMC ruled that Andrew Wakefield acted "irresponsibly" in carrying out his research

Rates partially recovered after the research was disproved but the volume of anti-vaccine sentiment on social media has increased in recent years.

This led Health and Social Care Secretary Matt Hancock to call for new laws to force social media companies to remove content that promoted false information about vaccines.

Prof Ball said there were rarely "side effects" with vaccines and even if there were, the benefits outweighed these.

You may also like:

"Because we have lived through a golden age of vaccination, we have forgotten just how harmful, and sometimes even fatal, these virus infections can be," he said.

Are students and others still at risk?

Dr Natalie Riddell, a lecturer in immunology and ageing at the University of Surrey, said a reduced amount of people being vaccinated against any contagious disease was dangerous.

"Babies and immuno-compromised people [such as the elderly or those receiving chemotherapy] rely on the rest of us to be vaccinated to prevent the spread of disease," she said.

"It is totally unnecessary for people to risk their friends and family becoming ill, or even dying, from measles or mumps, as there is a safe and effective vaccine to protect against both."

Prof Ball said poor vaccine uptake worldwide had led to an increase in outbreaks of mumps and measles and we should "expect things to get worse" before they get better.

The University of Nottingham has been hit by the mumps virus

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk, external.

- Published27 March 2019

- Published26 March 2019

- Published26 March 2019

- Published1 March 2019