Robin Hood Energy: The failed council firm that cost city millions

- Published

Robin Hood Energy - like its legendary namesake and Nottingham mascot - aimed to tackle social injustice

Council-run Robin Hood Energy set out to help people struggling with their bills, but instead it failed to turn a profit, ended up losing millions and is being closed down, leaving 230 workers redundant. Now that Nottingham City Council has decided to pull the plug on its grand project, BBC News looks at what happened.

Why was the company set up?

Fuel poverty can lead to health problems, according to the government

The council, it could be argued, began with noble intentions.

According to government figures, about 11% of households in England struggle to pay their energy bill, which can have a serious impact on health.

Robin Hood Energy (RHE) maintained that because it was not trying to make a profit, it could offer a cheaper alternative to dominant energy companies, external such as British Gas and EDF Energy - known as the "Big Six".

It hoped this would help tackle fuel poverty.

But offering cheap alternatives proved more difficult than RHE's simple mission statement suggested.

Were other councils doing anything similar?

Councils across the country own private companies - for example, Luton Borough Council is the majority shareholder of the company that runs Luton Airport

When it was established in 2015 Nottingham's council claimed RHE was the first local authority-run energy company in the UK.

Bristol City Council followed suit and established Bristol Energy that same year.

But they were not the only councils setting up their own companies - Nottingham's figures suggest about half of local authorities now own one.

Pete Murphy, a professor at Nottingham Business School, said since 2010 local authorities have been encouraged by the government to be more entrepreneurial with their resources.

He said less centralised oversight on how money was spent and the tightening of budgets amid years of austerity meant some took big risks and entered industries in which they did not have "the experience or skill" to succeed.

"They are almost forced into taking risks without any clear help or guidance [from central government]," he said. "It was almost inevitable it would fail for some council somewhere."

A spokesman for the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government said it was "monitoring the situation in Nottingham closely" and councils "should be held to account" if they did not manage public money properly.

How big was Robin Hood Energy?

The company claimed then Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn as a customer and was mentioned in his keynote speech at the party's 2016 annual conference

From small beginnings RHE grew to be a national player in just a few years.

At its peak it supplied energy to 125,000 customers around the country, many of these through council-run partners.

Its turnover went from £4.6m in 2015-16 to nearly £100m in 2018-19.

But, in all but one year, that growth translated not into profits but bigger losses and by March 2019 it was in the red by more than £34m, external.

Auditors Grant Thornton calculated the council had invested a total of £43m into the company and risked £16.5m in guarantees.

What went wrong?

In October 2019 the financial situation came to a head when energy regulator Ofgem threatened to withdraw RHE's licence over unpaid bills.

It demanded £9.5m within the month and RHE had to rely on the public purse to prop it up.

But the council was beginning to explore its options.

Last week it announced it would be selling the customer base to British Gas - one of the companies RHE had hoped to challenge - and would be shutting down the company - but admitted the sale would not make up for all of the losses.

What was the problem?

Bristol Energy also folded earlier this summer

Shortly before Bristol Energy was also recently sold, the city's mayor Martin Rees said the energy business was "the wrong one" for a council to try to enter.

"[It] is expensive to get into, expensive to operate in and expensive to get out of," he said.

This was no less true for Robin Hood Energy.

Grant Thornton, which carried out a Public Interest Report, said the council did not appreciate the size and the risks of what it was taking on.

The firm accused the council of "institutional blindness" with a determination that the company "should be a success", despite the deteriorating financial position, external.

Grant Thornton's report said: "This is not how local authorities should look after large amounts of public money."

Experts told the BBC they did not believe the company was "doomed to failure" from the start but the odds were stacked against it.

Ellen Fraser, energy analyst at Baringa Partners, said whether through "naivety or arrogance" a number of companies such as Robin Hood Energy were set up to beat the so-called Big Six, only to find it was "not that easy".

Ellen Fraser said the industry is "complex and hard"

She said balancing customers, industry processes and the fluctuating cost of energy in an already crowded market was complex and required access to large amounts of ready cash.

"Even the bigger players aren't making much money at the moment," she said.

Energy regulator Ofgem said there were currently about 60 suppliers operating around the country - down from a peak of 70 in 2018 but a big increase on the 10 there were in 2006.

What is the political fallout?

Council leader David Mellen said his thoughts were with the 230 workers who will now be made redundant

Leaked documents seen by the Local Democracy Reporting Service showed the council stood to lose £38.1m, although the exact final figure would not be known until the transfer of customers was complete.

The Labour-run council's opposition has called for resignations and described the scheme as a "white elephant".

Local government minister Simon Clarke said the city's leadership needed to decide "whether they are the right people" to lead after such a "disastrous waste of money".

So far, no senior councillors have answered the call to resign.

But the council has apologised and accepted there were "failings" in its governance of the company.

Leader David Mellen said: "When people say this was not a good use of money, I would agree.

"We couldn't continue to run it.

"It's not something we're proud of; it's something we regret.

"I've apologised to the people of Nottingham. We have to learn lessons from RHE."

Is this the end of council-owned companies?

Professor Murphy said councils can be "innovators" when running public services but may not be so experienced in the private sector

Catherine Waddams, an emeritus professor at the University of East Anglia's Centre for Competition Policy, said it probably spelled the end, for now, of councils trying to get involved in the energy market.

"There could be a model that works," she said, pointing out there were some ethical energy companies that have been going for a number of years.

But with coronavirus and its impact likely to hit council budgets hard and uncertainty in the energy market, she added: "Now is not the right time."

Professor Murphy said he hoped councils would stop getting involved in such big commercial projects outside their traditional areas of expertise.

He said: "I think it will make sensible councils think twice about this sort of investment.

"The public trusts councils to run the services they know about.

"Where they get more worried is when they start investing in areas they traditionally have little knowledge of."

But with councils facing little oversight, added to their need to find funds, he added: "There are bigger forces at play here and I don't think this will stop them in their tracks."

What does this mean for ordinary people?

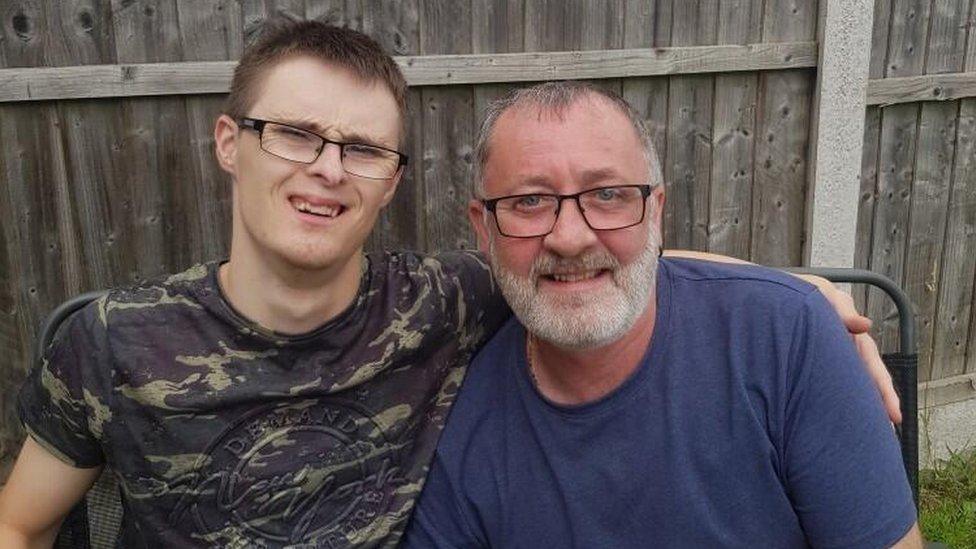

Frank Donaghy said "there's nothing else in Clifton" for his son to do, and he cannot afford to send him to a private day centre

RHE's 112,000 customers are now being switched to British Gas.

But the failure of the energy project has been a huge blow to the already cash-strapped council, just as it faced a multi-million-pound funding hole left by coronavirus.

On its website the council said, external during the period of the pandemic it had seen income lost from sources including leisure centres and car parks and costs rise in fields such as emergency care for older and vulnerable people and the provision of protective equipment. And it said "the Government has failed to meet its pledge to fully cover the cost of Covid to councils".

The authority said the money was being taken from reserves so it would not directly impact services - but it was left with less cash to fall back on if more cuts were needed.

Coronavirus had already prompted a review of services before the full extent of the RHE problem was made public, and one of those potentially facing the axe was Clifton's Summerwood Day Centre for adults with learning disabilities.

Frank Donaghy said for his son Andrew, who has Down's syndrome, the centre was like a "second family" and losing it would be a "deep deep loss".

He said he was "disgusted" by what had happened with RHE.

He added: "You hear about all the different things they're spending their money on and you think 'we're paying it in but the money is not going back in to the community'."

Follow BBC East Midlands on Facebook, external, Twitter, external, or Instagram, external. Send your story ideas to eastmidsnews@bbc.co.uk.

- Published4 September 2020

- Published3 September 2020

- Published22 June 2020